True Examples: What Is Missing and Not Missing from Lists of a Music Artist's Best Albums: Talking Heads: True Stories; Naked

~

Chronology:

1986, September: Talking Heads studio album True Stories released.

1986, October: feature film True Stories released; directed by David Byrne, written by Stephen Tobolowsky, Beth Henley, and Byrne.

1986, November: soundtrack album Sounds from True Stories released.

1988, March: Talking Heads studio album Naked released.

2018, November: Criterion Collection version of the film True Stories released; the deluxe edition includes an expanded version of Sounds from True Stories, entitled The Complete True Stories Soundtrack (or True Stories: The Complete Soundtrack), also available separately.

~

How do we make use of lists of the best, or most significant, albums, tracks, and compilations made by a musician or musical group, or of a certain genre or period? What is the purpose of making such lists? Obviously, if a list is short, regardless of the extent of an artist's recorded work, that list helps remind us, or recommend to the unfamiliar, what to listen to. If a list is long, it could still serve such a function if the artist has a large discography and both the listmaker and the reader agree that the artist is good enough to warrant such an extensive selection. But at times the Rock Annual list includes nearly all of an artist's studio recordings. What is the point of that? For example, seven out of eight Talking Heads studio albums are included—plus a concert album, The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads. As such, the reader learns not which of those seven are the best. What exactly is this level of quality or significance that those seven albums achieve by being listed so?

Consider, for example, in making my lists of major artists' essential albums, I recommend listening to 20 major albums by Frank Zappa (one of which is entirely a concert album, another almost entirely; and on others, Zappa mixed live and studio recordings in a way that renders the distinction blurry) plus two albums in the experimental annex, 17 (mostly-)studio albums by Neil Young (he also liked to mix in live recordings, 16 studio albums by Bob Dylan (or 15, if you would prefer to place the original 1975 Basement Tapes in the category of archival albums, which get thrown in with compilations)), 14 studio albums by David Bowie, 14 studio albums by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (including Grinderman in that total but not the Birthday Party), 13 studio albums by the Fall, 11 studio albums by the Rolling Stones, 10 studio albums by the Beatles, 10 studio albums by Sonic Youth, and ten major albums by the Grateful Dead (6 completely studio, 3 concert, and 1 studio album with live recordings mixed in) plus 4 solo albums by the band's members not classed under the Grateful Dead.

Those are the artists with the most "essential" albums. But there are individuals whose work is spread across more than one artist entry: notably, Lou Reed has nine solo albums listed, including one collaborative album with John Cale, and was the leader (essentially) of the Velvet Underground, whose four studio albums, plus a concert album, are included. Cale played a crucial role on the first and second Velvet Underground albums, and has six solo albums listed. Nico, briefly an addition to the band, has three solo albums listed. The Wailers (that is, including Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, regardless if they were billed as Bob Marley and the Wailers) have four albums listed, Marley has another four, plus there is one solo album each for Tosh and Bunny. Peter Gabriel has four solo albums listed and was the leader (essentially) of Genesis in the band's early phase, from which four of their five listed albums come. His successor as the band's singer, Phil Collins, has one album listed as well. Or groups with extensive overlapping of members: notably, Funkadelic (five albums), Parliament (four albums), and Bootsy's Rubber Band (one album) together reach double digits. Fairport Convention and two of its members, Sandy Denny and Richard Thompson, collectively have 13. Similarly, eight albums total from the four Beatles' solo careers are included. Yellow Magic Orchestra's included albums, added to the included albums by its three primary members, Haruomi Hosono, Ryuichi Sakamoto, and Yukihiro Takahashi, total to 14—all but one of these being released in the years, 1978-1982! On top of that, Hosono was a member of Happy End, who have one album listed, and there are a further five albums by Sakamoto, from the later phase of his career, in the experimental annex.

A few of these artists, namely Zappa, Young, the Dead, Dylan, and the Beatles, have an inordinate number of archival releases that, in my estimation, count as crucial additions to their discographies. So do Prince (who has eight studio albums listed, plus archival releases focused on three of those albums), the Beach Boys (eleven studio albums including one solo album apiece from Brian Wilson and Dennis Wilson plus two archival releases), King Crimson (eight studio albums including Robert Fripp's Exposure plus three archival releases), Pink Floyd (6 studio albums plus its massive Early Years box), and the Residents (six studio albums plus an album in the experimental annex and a box set including three additional studio albums with related material, those three albums arguably best appreciated as a whole), thus making them more prevalent than artists with a similar number of studio albums but without such a backlog of material left in the vaults (namely, R. E. M. (9), Tom Waits (9), Led Zeppelin (9), Black Sabbath (8, not including a solo album apiece from Ozzy Osbourne and Dio), Todd Rundgren (8, including one album originally credited to Runt and two albums by his side-project band Utopia), Sun City Girls (8, not including two solo albums from Richard Bishop and one album from the Alan Bishop-led Invisible Hands), the Cure (7), Stevie Wonder (7), Van Morrison (7, not including an album with Them), Aretha Franklin (5 studio, 2 live), Elvis Costello (7), Joan Baez (7), Chet Atkins (7, including two collaborative albums), Captain Beefheart (7), the Temptations (6, not including one Eddie Kendricks solo album), and Roxy Music (6, not including one solo album each from Phil Manzanera and Bryan Ferry or short-time member Brian Eno's work). Talking Heads also belong in this category, having released little archival material. Some artists (Johnny Cash (8 studio albums), Elvis Presley (8), Fleetwood Mac (8, not including two solo albums from Stevie Nicks, one from Lindsey Buckingham), Bruce Springsteen (6 studio, 1 live), and the Doors (6)) have given birth to extensive archival releases arguably less significant to understanding their oeuvre.

Talking Heads, 77

Originally released 1977, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

Having said that, what other information can be gleaned from a recommendation to listen to eight, instead of nine, Talking Heads albums? (Plus one single, by the way: their debut, ‘Love Goes to Building on Fire’ and one track from the excluded album—more on that album in a moment.) First of all, however indirectly, the list disputes any claim that Talking Heads belong in a category of artists who produced influential, perhaps revolutionary, work for a short period of time then not only struggled to replicate such a degree of innovation and inspiration over a longer period—as any artist would—but also fell by the wayside, making little if any music of enduring quality or even contemporary notice. This is the story of many Rock bands: for example, contemporaries of Talking Heads like Cheap Trick, X, Gang of Four, or Tom Verlaine. In short, the group's later, longer phase (from Speaking in Tongues until the end) deserves close, devoted attention. What is probably most debatable about this position is the group's final album, Naked, being placed at the same level, roughly speaking, as their much-lauded early albums. Perhaps Little Creatures being placed at the same level also surprises. Again, though, when I say, “roughly speaking,” I mean it. Between albums that “make the list” there lie significant gradations of quality, so I am not claiming, for example, that Naked is as good or significant as Remain in Light. Such a broad categorization does mean in this case that I feel more compelled to talk about Naked, the album frequently forgotten, and True Stories, the album not listed. Have not those early influential, revolutionary albums been analyzed enough? (Probably not, at least not analyzed well.)

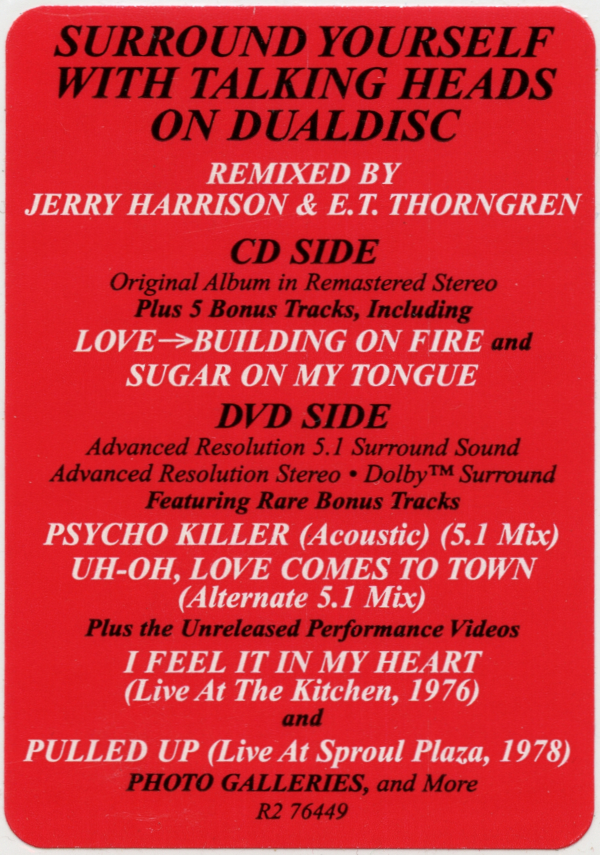

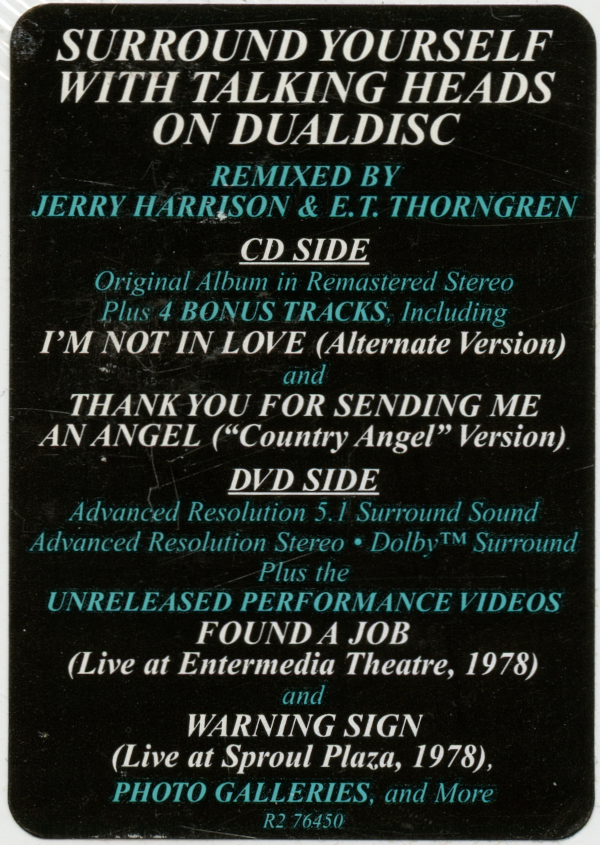

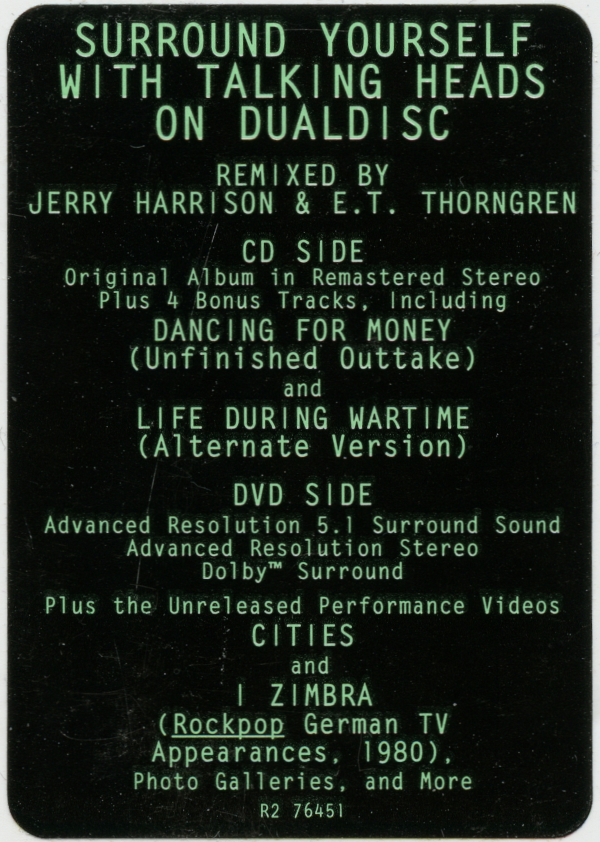

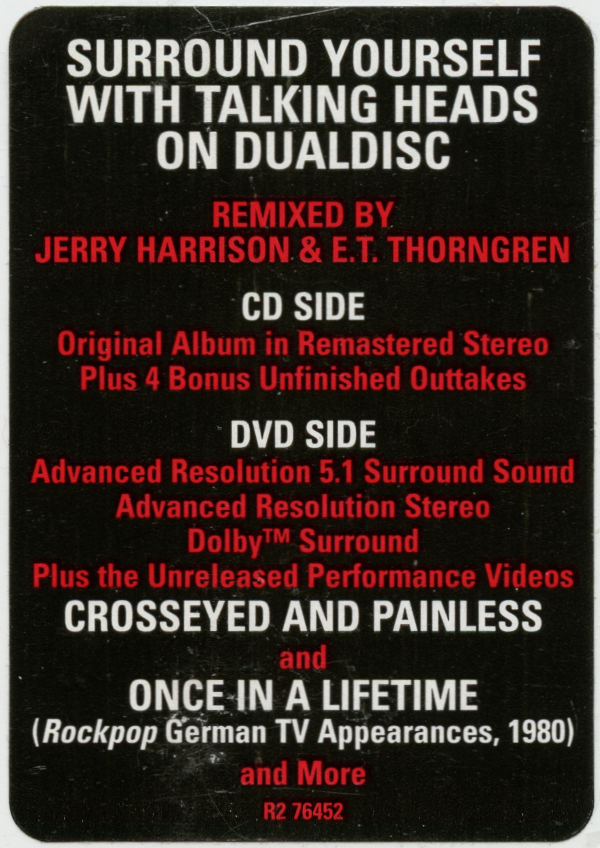

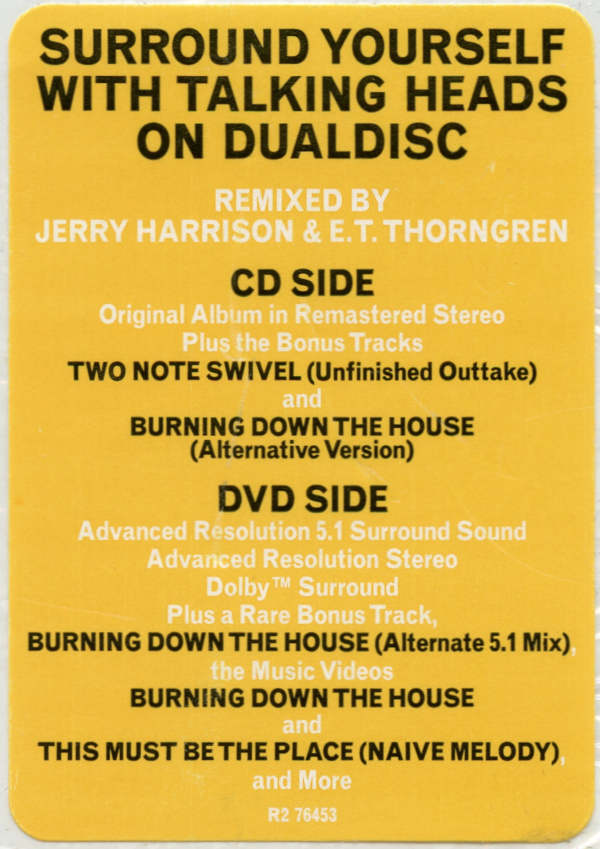

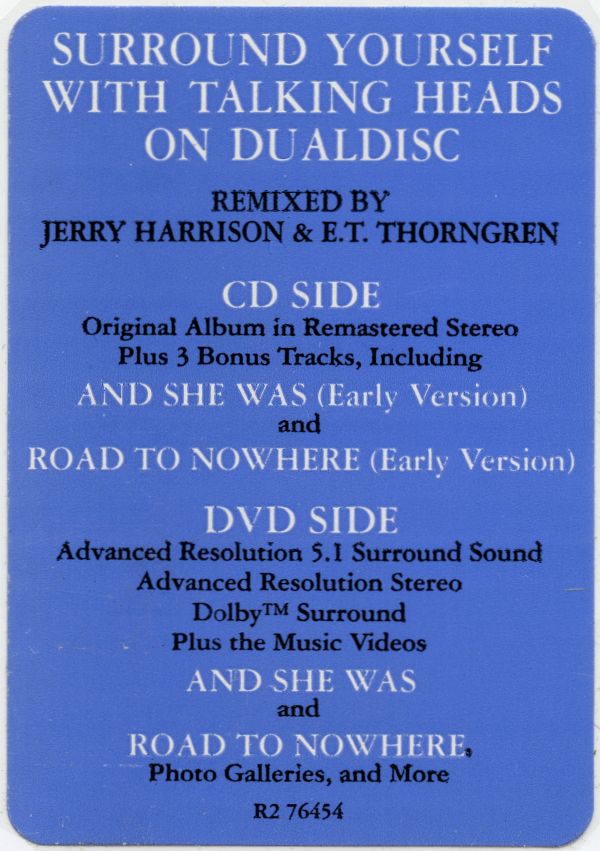

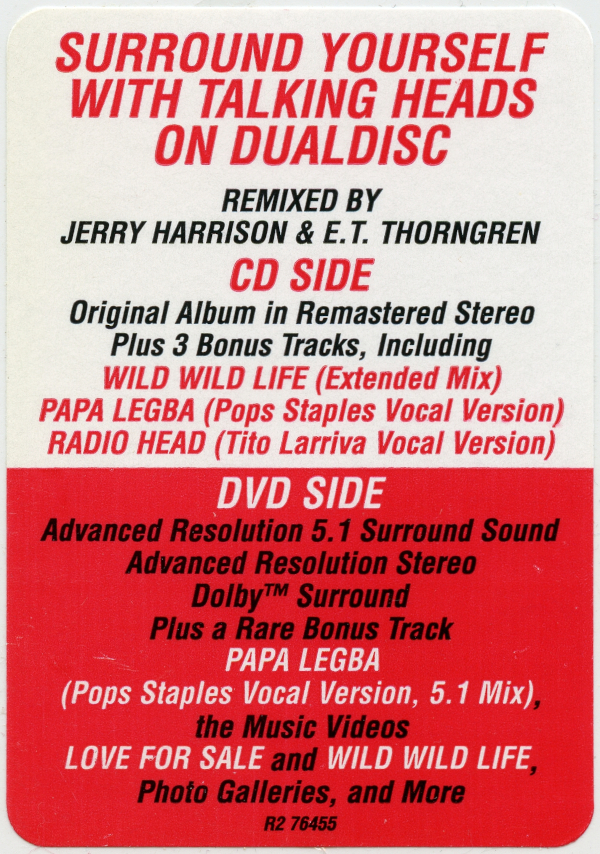

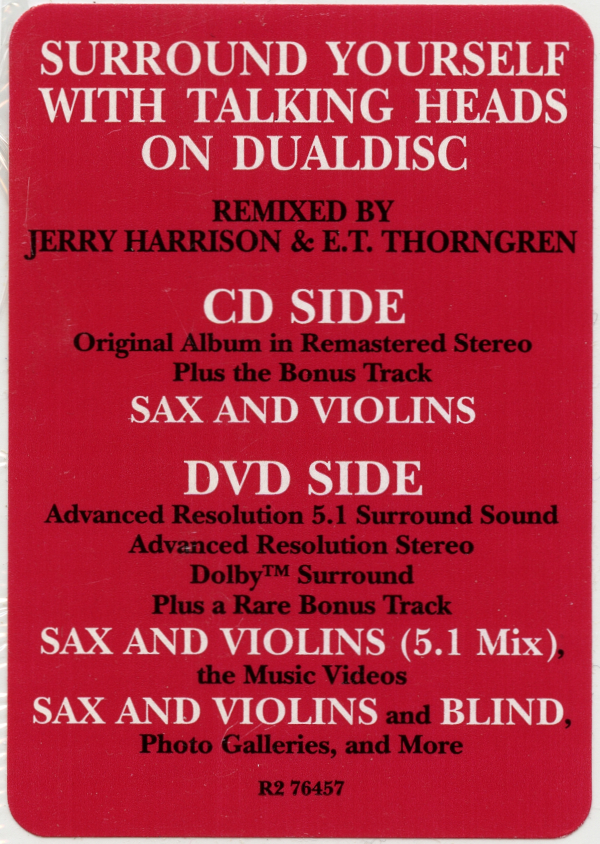

For roughly twenty years, while I had copies of most Talking Heads albums on vinyl (and, later, all their studio albums when reissued in the curious hybrid C. D.-D. V. D. format (looking like two discs glued together) allowing for both stereo and surround-sound mixes [see the hype stickers on display here] plus the expanded 2004 version of The Name of This Band) I rarely listened to Naked. When I was young, I can only assume, it seemed too refined, too clean. The synthesizers heard so prominently on Speaking in Tongues had apparently been silenced by the straight-ahead Rock heard on much of Little Creatures and True Stories, though they do resurface on ‘The Facts of Life’. The “Latin” rhythmic flourishes and West African guitar stylings reeked of the plundering of “World” sounds and concomitant employment of such “World” musicians in a manner that suggests condescending paternalism. The influence of genres clearly different from European/ North American Rock norms in the middle-1980s too often seemed to clash with the regimented world of Eighties popular music or, alternately, threatened to zap the life out of younger, dynamic, often transnational music scenes and cultures. If Paul Simon's Graceland is brilliant (it is) then it achieved its brilliance from Simon, for better or worse, immersing himself in a different musical scene. It may have reflected his vanity, but it did not do so superficially. In retrospect, Naked may serve as a counterpart to Graceland. Recorded in Paris, with guest artists of a “World” variety but also closer to home (Johnny Marr guitar, Kirsty MacColl backing vocals, a few Jazz arrangements) and David Byrne's lyrics ranging from broad themes like human evolution to narratives driven by hazy maybe-memories of minute details that lodge themselves in the listener's mind (“Claimed he was a terrorist/ Claimed to avert catastrophe”; “I miss the honky tonks, Dairy Queens and 7-Elevens”; “It's a big day for Mr. Jones/ He is not so square”—take that, Bob Dylan?) Naked is nothing if not ambitious.

Talking Heads, More Songs about Buildings and Food

Originally released 1978, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

The album, however, stumbles on its second side, with two tracks, ‘Mommy Daddy You and I’ and ‘Big Daddy’—or three, if you include ‘Bill’, found only on the cassette and C. D. versions—in succession that do not seem necessary to the whole experience. A severe edit would remove all three tracks but make ‘Sax and Violins’, originally released in 1991 on the Until the End of the World soundtrack album but recorded during the Naked sessions, part of the original album instead of being the bonus track it later became. This shorter album of nine tracks would be closer in length to the rest of the band's albums. In other words, Naked would not seem like a victim of longer-album-itis, the disease that has struck many albums since the late Eighties, when the dominance in the market place of cassettes and C. D.s began to make 50-minute, 60-minute, and 70-minute uneven affairs out of what should have been 40-minute minor masterpieces. An easier fix is to nix only ‘Mommy Daddy You and I’, an intriguing piece, no doubt, a sort of (boring) short story set to music, but with its structure relatively standard compared to the rest of the album's songs. Every time I've listened to it recently, upon its abrupt ending, I feel like I just endured a preening newbie test-run his song-as-final-exam in a songwriting class where the word, “craftsmanship,” is uttered ad nauseum. ‘Big Daddy’ works well enough, with its star harmonica accompanying the same horn section heard earlier on ‘Blind’ and ‘Mr. Jones’; it would not feel right to hear those sharp musicians prominently early in the album then never again. And ‘Bill’ can still serve, as it always has on C.D. versions, as an effective transition into the darker hues of ‘Cool Waters’.

Talking Heads, Fear of Music

Originally released 1979, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

As soon as I entertain this re-tracking, more ideas come flooding in. If only ‘Mommy Daddy’ is removed—and especially if it is removed and replaced by ‘Sax and Violins’—the album is still awfully long. Perhaps, to include ‘Sax and Violins’, we need to eliminate ‘Big Daddy’. Another option is to remove ‘Mr. Jones’ and make ‘Big Daddy’ the second track instead. ‘Mr. Jones’ seems to stand apart to a greater extent, especially in its lyrics. Does it fit in? Maybe it could have been a separate single. Of course, with either ‘Big Daddy’ on the first side, or excluded, we have the awkward situation I wanted to avoid: the tracks with horns only being at the beginning of the album. Maybe that's fine; the B side in general, not just ‘Cool Waters’, features fewer of the bright sounds, up-tempo rhythms, and lighter subject matter of the A-side tracks. Without ‘Mommy Daddy’, ‘Big Daddy’ (was there not anyone to suggest that two tracks with the word, “daddy,” in the title, was a bad idea?) clashes with the rest of the B side. The track that precedes ‘Mommy Daddy’, ‘The Facts of Life’, is the longest on the album, an epic that arguably stands as one of the band's finest compositions and recordings. Perhaps ‘Bill’ is needed as a shorter, minor track to bridge between ‘Facts’ and ‘Cool Waters’. So let the “sax” tracks be confined to the first side and keep ‘Mr. Jones’ not ‘Big Daddy’ to respect the original order.

Talking Heads, Remain in Light

Originally released 1980, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

As soon as I say that, however, I begin to wonder why I assumed that ‘Sax and Violins’ comes last. Simply because it has only been a bonus track tagged on at the end? ‘Cool Waters’ has been the final track on nearly every version of the album for a good reason: it works perfectly as a closing song precisely because it progresses dramatically from a bare start to a surging conclusion with Byrne's strenuous vocals especially standing out, a narrator on the verge of emotional exhaustion; similar vocal exertions from Byrne having already been heard on ‘Blind’ and ‘The Democratic Circus’. Coming as it does, though, after the album's pace had begun to lag, the track had been wasted. Few concluding tracks successfully leave the listener wanting more, ‘Cool Waters’ is one of them. ‘Sax and Violins’ should come before it. So a restructured Naked would run as follows:

‘Blind’

‘Mr. Jones’

‘Totally Nude’

‘Ruby Dear’

‘(Nothing But) Flowers’

‘The Democratic Circus’

‘The Facts of Life’

‘Bill’

‘Sax and Violins’

‘Cool Waters’

To summarize, Naked may not have quite gelled as a cohesive album in its original form, but it offers enough material out of which, with two tracks excised, one added, and a slight edit in the tracking order, a cohesive album could have easily been made. The longer-album-itis of this era undoubtedly offers many other albums in a similar state. Clearly there needs to be a limit beyond which inferior tracks that should have been out-takes cannot be dismissed. If the Guns n' Roses Use Your Illusion albums had been a single C. D./ double L. P. instead of two C. D.s/ two double L. P.s, while it would have made for a better album (in my view, better than Appetite for Destruction, albeit with fewer stand-out, iconic hits), it also makes for a lot of rejected material.

Talking Heads, Speaking in Tongues

Originally released 1983, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

And so on, backwards-chronologically, to True Stories. Though marketed as a Talking Heads studio album—as indeed it is—it is also part of a larger project and arguably cannot be fully appreciated as separate from that project. And yet, the entire project: the film; the various-artists soundtrack album, Sounds from True Stories; an expanded soundtrack, The Complete True Stories Soundtrack, long hoped for, finally released in 2018 to accompany a Criterion Collection Blu-Ray of the film; and the Talking Heads studio album, is definitely an essential artifact of popular culture. Filmed in the Dallas area, but set in a fictional small city, the film presents Texas, and by extension much of the Sun Belt that was then attracting migrants and businesses at the expense of the declining Rust Belt, as a cartoonish Utopia. For all the humanity thus ignored, the fantasy world created by the film certainly captures the devil-may-care freedom—from history, social obligations, cultural standards—that the privileged residents of suburbia, especially the children, felt of the post-Vietnam, post-stagflation era. Sun Belt suburbanization served as the true final United States frontier (instead of outer space, as John F. Kennedy famously promised). Lacking both an agrarian frontier or an overseas colonial frontier that the historian Frederick Jackson Turner had postulated Americans would need after the “closing” of the West in the late Nineteenth Century, the new housing and business developments of the New South (Southeast, to be exact) and the same old Southwest became the new promised land wherein Americans could leave nagging political problems behind, dismiss them as mere nuisances created by those stuck in the past. Even in the present day, well past the peak years of Sun Belt expansion, if I find myself in a suburban area with structures largely built since the Eighties, I feel that sense of freedom: all the buildings are crap, so there is no need to care for them to preserve them; the neighborhoods are new and have no history, so there are no depressing thoughts of regret and nostalgia bundled up with them; the available food has all been made largely by machines and there are no parks or other opportunities for physical exertion unless they are paid for, so let your body go to waste; and of course let your mind go to waste—in the era of tiny televisions, the easy part. This is the freedom portrayed in the film, especially when the protagonist, played by David Byrne, ruminates about metal buildings and tract housing. Not to mention the roseate view of computer technology offered in the scenes taking place at the Varicorp company, still not out of place among the over-educated American elite of this new millennium. In the documentary about the film included with the Criterion release, Byrne emphasizes the flat Texan landscapes, especially how buildings set against those landscapes seem isolated from any context.

Talking Heads, Little Creatures

Originally released 1985, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

True Stories can at least be said to present the suburb-as-utopia beloved by many Americans in a manner that invites all manner of interpretations. Is the entire film, especially Byrne's character's narration, breaking the fourth wall as it does, deeply, impenetrably sarcastic? The characters hopelessly pathetic and deluded? That is a fair take, though clearly not that of those involved, including Byrne and others interviewed for the documentary or Spalding Gray (in a Vogue article included in the Criterion notes). A better interpretation, perhaps, is that this fake city, Virgil, Texas, shows us an ideal version of suburban communities. Given that we seem to have no possibility in this nation of our fellow citizens seeking out a non-imperialist way of solving societal problems, why not approach suburban “escape pod” culture in a manner more humorous, even whimsical? An approach that in turn allows Byrne and company to concoct characters and scenarios, however absurd on the surface, with which the viewer can empathize. Having said all that, True Stories also gives us a revealing glimpse into small-town life, except that the town in question, (non-fictional) McKinney, Texas, where a parade and other downtown scenes were filmed, is a perfect example of a small town swallowed whole by a larger city, thus turned into a suburb. More exactly, McKinney in the Eighties, was still a small town but has experienced dramatic population growth since. In that aforementioned documentary, Byrne and others point to local, vernacular cultures (not necessarily from the Dallas area, but all to some extent Texan) that either inspired aspects of the film, such as Las Floristas headdresses, or were directly featured in the film, like the Tejano accordion stylings of Esteban Jordan, as well as participants in a local talent show that the film crew organized. The problem being that these small-town and rural cultures were being displaced by suburban developments. Is this the other deeper context here? After all, when Americans turned the search for a new frontier inward, they made fellow Americans the victims of expansion.

Talking Heads, True Stories

Originally released 1986, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

What about the music? Unlike with Naked, we need not rearrange anything ourselves. A mess already awaits in the complex relationship among the three aforementioned albums. Some of the songs featured on both the Heads album and the film work better as performed by the actors: namely, ‘People Like Us’ (sung by John Goodman), ‘Puzzling Evidence’ (John Ingle, backed by the Bert Cross Choir, an actual Gospel group), and, arguably, ‘Dream Operator’ (Annie McEnroe). ‘Hey Now’ is the opposite: only presented in a rawer, shorter form in the film, as sung by children, the Talking Heads version can be considered the final, superior version. ‘Radio Head’, in the film sung by Tito Larriva of the Plugz, for me works better as a Talking Heads song; Byrne exploits the song's melodic potential to a greater extent than Larriva. Finally, ‘Papa Legba’ works brilliantly in both Talking Heads form and as sung by Pops Staples of the Staple Singers. These non-Talking Heads versions, originally only heard in the film, are now available on the Criterion soundtrack. An unfortunate peculiarity about the expanded Criterion soundtrack, however, is that one of the 14 tracks included on the Sounds From True Stories, ‘I Love Metal Buildings’, has been shortened on the new release. Even worse, two of the non-Talking Heads versions, Staples' ‘Papa Legba’ and Larriva's ‘Radio Head’ were both slightly longer when released as bonus tracks on the earlier hybrid C. D.-D. V. D. reissue of the Heads True Stories.

Seemingly, these abridgments helped fit the material onto a single disk. This is an awful misstep. Why not simply include the entire soundtrack, without these edits, on a second Blu-Ray disc? Presumably another Blu-Ray (or a double C. D.) would have added to production costs. To keep it as a single C. D., the expanded soundtrack could have easily excluded the three Talking Heads tracks featured in the film (‘Love for Sale’, ‘Wild Wild Life’, and ‘City of Dreams’) that have always been available on the Heads True Stories. Thirty seconds or so may not seem like much, but presumably anyone buying the expanded soundtrack already has True Stories. And of course wthout the Talking Heads tracks, there would be room for the unabridged versions of those three other tracks.

Talking Heads, Naked

Originally released 1988, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

Talking Heads DualDisc reissues, 2006

But there is another possibility. Such a diversity of material arguably does not hold together as a cohesive album, especially if those three Talking Heads tracks are removed. In that scenario, the 14 mostly-instrumental Sounds tracks would perhaps overwhelm the six film songs. A third version of the soundtrack album could solve this problem by mixing in all of the Talking Heads album True Stories. That is, there would be six songs (‘People Like Us’, ‘Puzzling Evidence’, ‘Dream Operator’, ‘Hey Now’, ‘Radio Head’, and ‘Papa Legba’) presented in both the film versions and the Heads versions. Now quite a lengthy affair, would the repetition of six songs again make for a messy album? It does at least make the “interstitial music,” as Byrne calls it in the Criterion liner notes, less dominant. After all, if Sounds from True Stories has not been preserved in its original form, why not make this extended version of the extended soundtrack (which would indeed have to be a double C. D.) proposed here render the Heads True Stories redundant as well? One could argue that such a large number of Talking Heads songs being part of what is overall a various-artists compilation would make for a jarring listening experience. A fair critique. As with our re-tracking of Naked, these alternate histories rarely leave our computer screens (or a burned C. D.-R).

True Stories

Film and soundtrack originally released 1986, reissued 2018 (Discogs)

Talking Heads, The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads

Originally released 1982, reissued 2004 (Discogs)

Talking Heads, Stop Making Sense album

Originally released 1984, reissued 2023 (Discogs) with nine bonus tracks—seven of these additional tracks having been included with the 1999 reissue

Talking Heads, Stop Making Sense film

Originally released 1984, reissued 2024 (Discogs) with additional audiovisual material

Either way, the Criterion Collection release, especially the Blu-Ray package that includes the soundtrack C. D., is a necessary addition to the music library of any Talking Heads listener. My approach to cataloging does not count audiovideo releases toward a music artist's total major albums. As much as, for example, the 2003 eponymous Led Zeppelin D. V. D. set serves as an exemplary Zeppelin concert album, it nonetheless comes in audiovideo form and is not listed. While the Talking Heads True Stories album stands apart from the film, as do, for example, the Prince albums Purple Rain, Parade, and Graffiti Bridge, neither of the two variants of the soundtrack album can be meaningfully separated from the film. Similar examples abound, not least several later Residents projects, and of course none other than Talking Heads' concert film Stop Making Sense.

–Justin J. Kaw, November 2020