Seas of Meaninglessness—Words in Rock Music

Having spent a good part of my life listening to songs as they have been created and documented since the Sixties, I have also heard many sung words without giving much thought to the meaning behind them. That is another way of saying: having listened to singers in Rhythm and Blues/ Rock-and-Roll and related genres much more than I have singers in Jazz, Folk, and Classical musics, I listen for the melody, and the sound of the voice; the literary content is an afterthought. I may make out a word or two per each line of verse, hardly enough to appreciate the whole lyric, let alone savor and appreciate it as one would do a poem.

Of course, certain singers leave their audiences with no choice but to know the words: they sing with sufficient enunciation, and the accompanying music is not sonically dense or is made to be lower in volume during the mixing process, such that the words arrive at our ears already deciphered. Or if their words do not come through so clearly, certain singers provide the lyrics, so you can read them as you listen, or before or after. If the original releases did not provide them in liner sheets and booklets, they have sometimes been made available in book form or online. Bob Dylan, at his web site. Lou Reed, in the book, I'll Be Your Mirror: The Collected Lyrics. These two conspicuous examples, though, are exceptions: Dylan came out of the Folk Revival, where songbooks were common, and he and his handlers eagerly sought out others to cover his songs, as was commonly done then; Reed, on the other hand, learned about writing from the poet Delmore Schwartz and aspired to literary greatness. Another singer, Leonard Cohen, published poetry before he turned to music; in an alternate history, he never becomes a singer. In recent times, David Berman of the Silver Jews/ Purple Mountains won some acclaim for his book of poetry, Actual Air, and Nick Cave has published novels. Again, these are exceptions. And the availability of lyrics does not mean that I, the listener, actually pays any attention to them beyond the moments I spend listening to the music.

The likes of Reed, Dylan, Cohen, and Cave are exceptions for good reason: the words in popular music are often tossed-off drivel. They are often supposed to be so: the melody comes first, is more important; the words must find their way in. Besides, songs, being the voice of the "common people," if not striving to capture "stream of consciousness" inner thoughts, tend toward the conversational and as such are theatrical. If the singer is playing the role of everyman, or a stupid man, an angry man, a "jealous guy"; a righteous buffoon, a regular buffoon—whomever... if the words fit, they are fit to print—or not print, but sing. From "yummy yummy yummy, I got love in my tummy" to "a mulatto, an albino, a mosquito, my libido," what would not pass muster as poetry works well within the intermedia shapes of song. (And a song, because it presents a poem in musical form, does not find itself subject to the same standards as non-vocal compositions.) No surprise, then, that there are endless songs for which the words are only partially known. More accurately, they are guessed, inferred, and the results in this century are presented audiovisually at numerous nondescript advertisement-laden web sites.

The concern that I raised at the beginning of this piece is perhaps best addressed by this concept of intermedia: songs are not poems, they are music and literature at the same time. So what standards are we to use? Perhaps they can be found in other intermedia, most obviously the many poets, from William Blake to Kenneth Patchen, who have accompanied their writings with visual art. And I don't mean only standards of criticism. I mean, the models by which we choose to listen to lyrics. Should we always try to decipher songs that we like, to write out the lyrics if they are not easily available or the transcriptions that we do find seem wrong? Not only that, but should we try to sing them ourselves? (Now we have arrived at producerist, D. I. Y., Punk critiques of consumer culture—let's not digress. And let's not even talk about karaoke, except to ask: do those lyrics come from official sources ever? Are there back-channel sources of lyrics that I do not know of?)

Either way, without official versions, the words remain in a state of uncertainty. Some song composers want their listeners to make up their own words. "Indeterminacy." When I attempt my own transcriptions, to climb my way out of the semantic murkiness of mostly listening to music for the sound, instead try mightily to focus on the words, I find the task hard. You can listen to a song over and over again, pause it over and over again while listening to it, to allow your slow writing-out of the words to catch up with the singer's speedy delivery. So often, though, there are words that I do not begin to suss out, the identity of which I cannot hazard a single guess. What if we spend our whole lives singing the "wrong" words the singer never sung? Does this matter?

Often, an attempt on the song composer's part to raise the literary standards of his songs simply comes off as "pretentious," a word mysteriously made into a negative by legions of moronic denizens of popular culture who apparently do not understand that all art is pretentious—thank goodness for that. Nonetheless, we must admit that song lyrics that seem difficult to understand, especially when we can only decipher part of the lyrics, and the singer, despite apparently being intent on practicing poesy, cannot be bothered to provide us with the printed texts, can be awfully annoying. Thurston Moore: "Mother Africa, awake your son"? Please, after I kill myself. In other words, provide some lyric sheets or some explanatory notes—or be prepared for eye rolls, groans, head shakes, delivered for good reasons or not, from the same persons probably feeling nauseous from reading this essay.

Meanwhile, I can't be the only listener who has found the sight of hundreds of fans at concerts singing along to arcane phrases from songs as if they were the exact words one would expect to constitute propaganda, ritualistic chants, war cries, commercial slogans, and what-have-you not to be a source of joy but more a sign of something dark and apocalyptic to come. Sure, go ahead and maniacally sing along to "Feel like makin' love" or "We will rock you," but "Toys! Toys! Toys in the attic"? "We're off to never-never land"? These situations can easily lead one to dismiss the very idea of sophisticated lyrics in popular music. Let's keep it simple: "Take me down to the paradise city" may be about as ambiguous as you want to get.

--

Before the electronic amplification of sound, singers had to enunciate words well because the act of doing so came along with, was a necessary condition of, singing loud enough to be heard in a theatre. The modern microphone, though, famously allowed singers to adopt new "up close" styles associated with "crooning" singers like Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra.

Jazz singers may have had the training or, if not, the untutored skill to enunciate words clearly enough for the listener to ably decipher every single word, but Rock singers often have not. Nor would we want them to. The timbral complexity of singers of a Folk or Blues background, or who were influenced by such singers, is impossible to separate from the difficulty the listener experiences in recognizing words that they sing, especially when they sing quickly or accompanied by distracting layers of sound. As these singers, from Ma Rainey to John Lennon and beyond, entered the world of popular-music sound recording, wherein even singers of a Jazz or musical-theatre background, from Marion Harris to Tony Bennett, adapted their methods to the possibilities of not only the microphone but ever-advancing techniques of editing and manipulating sound, the notion of the singers on our hit parades having Classical training or even able to sing "in tune" came to seem quixotic, then moot. Meanwhile, those new possibilities of recorded sound allowed for an incredible density of arrangements and textures, especially with enhanced multiple-track recording of the Seventies. Compare Roxy Music's early albums to the music that inspired them from the Fifties and Sixties. Sometimes, the star singer, Bryan Ferry, barely climbs his way out of the elaborate array of instruments and effects, let alone sing in a way that would allow the listener to grasp every word he utters.

The other pivotal historical development was the post-Dylan rise of the "singer-songwriter." Only with the commonality of the singer who is also a composer, who mostly sings his own songs, could we have a situation wherein the listener is hard-pressed to find official lyrics. Of course, in the initial post-Dylan days, especially with the enhancement of album packaging, lyric sheets became more common. But in the long run, the "singer-songwriter," unlike the professional songwriters of Tin Pan Alley/ Brill Building fame, can keep his songs all to himself, as if we are so very privileged that he chose to share them with us; in stark contrast to the professional songwriter eagerly selling his wares. The "singer-songwriter," who after all wants to sing, not write, may not want his creations to be judged against literary standards, or may want them to be so judged, but only if they are not judged harshly. He should know, however, that he has no choice in the matter. Us listeners will hear his words, we will decipher some of them, and we will assess them—perhaps only subconsciously, in our listening choices. If the singer wants the listener to guess the words, then the singer must be prepared for the guesses to be awful. "Excuse me while I kiss this guy" and all that.

A concise take on the revolution in popular music that took place in the Sixties presents it as a three-pronged process. First, the Beatles went out of their way to compose their own songs. Then, Bob Dylan, a folk singer who had moved away from traditional and topical songs toward introspective, textually-complex (if not sophisticated) works, decided to play Rock-and-Roll. Around the same time, the Byrds covered his ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’, not even one of the shorter, Rock pieces on side A of his recent album, Bringing It All Back Home, but rather one of the longer pieces he performed solo-acoustic on that album's B side. The Byrds cut out much of the lyric, but still... the dynamic was there: poets backed by an amplified band. You may get the words as text when—if—you buy the album, but you may not, and either way if you have to consult the lyric sheet to figure out the words, you expend time and energy that would not have been spent if the words had been simple and apparent to begin with. Time and energy that could have gone to creative pursuits, including attempts at being your own "singer-songwriter" mumbling and slurring your way through songs that your listeners will strain to divine the meaning of.

As we are able to decipher fewer sung words, the lyrics become less like text and more like conversation, or even overheard phrases—snippets of others' conversations. Without official versions, lyrics face the prospect of never reaching "written" status. Again, perhaps the singer does not want his words to take such form. Nonetheless, we can all recognize that if we do not bother to make out every word that a person speaks to us, then we must not care too much about the content of what is being said. For many listeners, including me most of the time, the exposure they have had to lyric sheets or in recent years those awful web sites (when you find it annoying that you cannot make out a particular word)—and, again, let us forget the temptations of those karaoke nights—has been enough already. It turns out that I don't care.

On the other hand, we do still care about the music, or more precisely the performance, the enacting, of the lyrics. Perhaps the most impenetrable, inscrutable singer-songwriter is the Fall's Mark E. Smith. Like many of the singers who emerged in the Punk years, one feels as if we are besmirching Smith's vocal-literary works by calling them songs. Fall performances used Rock music as a platform for Smith to enact psychodramas only on occasion meant for his audiences' comprehension. Not are only the words he uses difficult to decipher, but when they are clear—scattered phrases like "spoilt Victorian child" or "the North will rise again"—when much of the remainder of the song is so beclouded, they remain supremely ambiguous. Perhaps, in this sense, poet-singers like Smith, whose poetry we are not even allowed to read, take the extreme Modernism of James Joyce's Finnegans Wake to another extreme. So obscure it's not even there. Or more Indeterminacy, so much Indeterminacy that John Cage would get flustered.

--

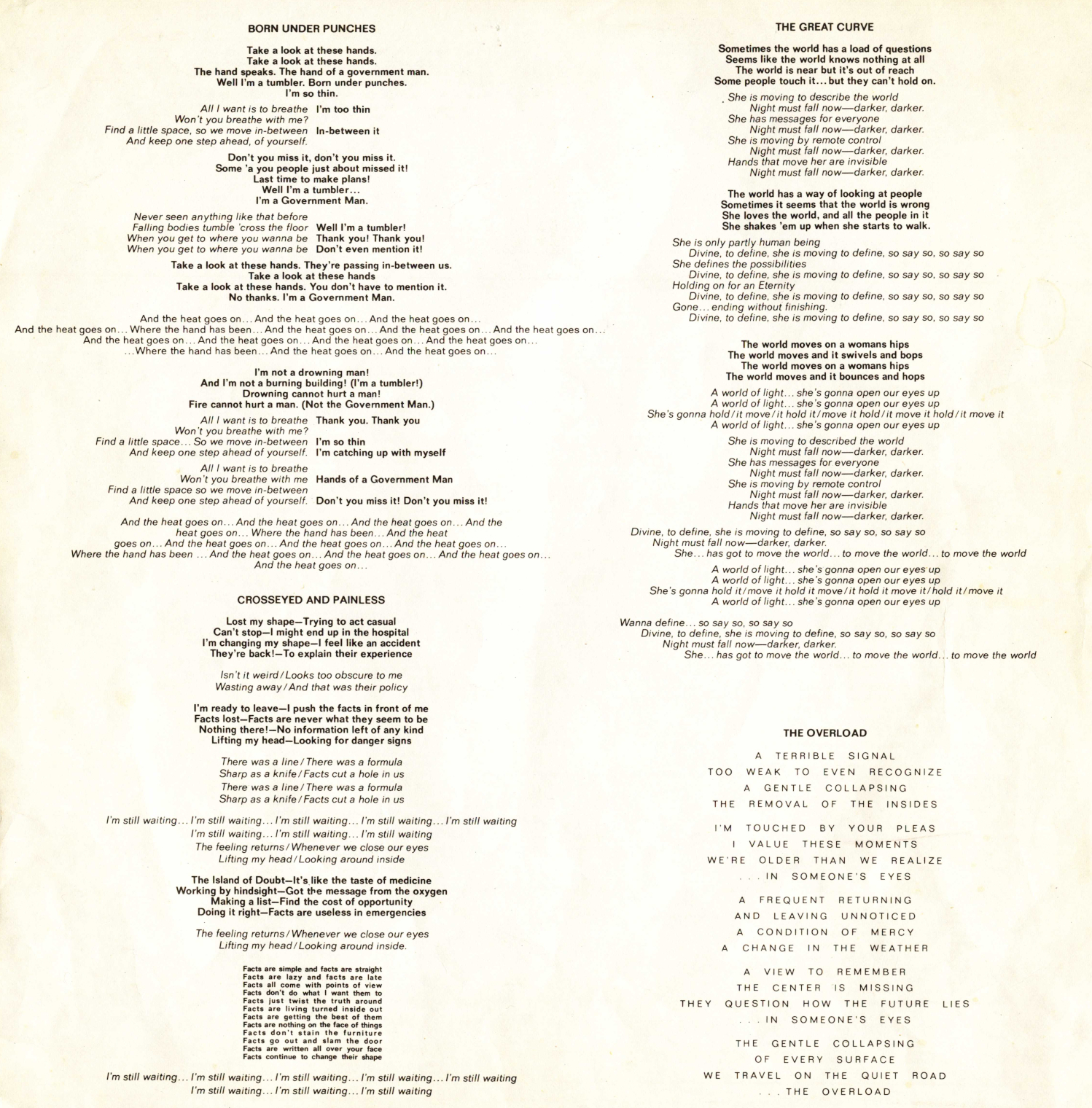

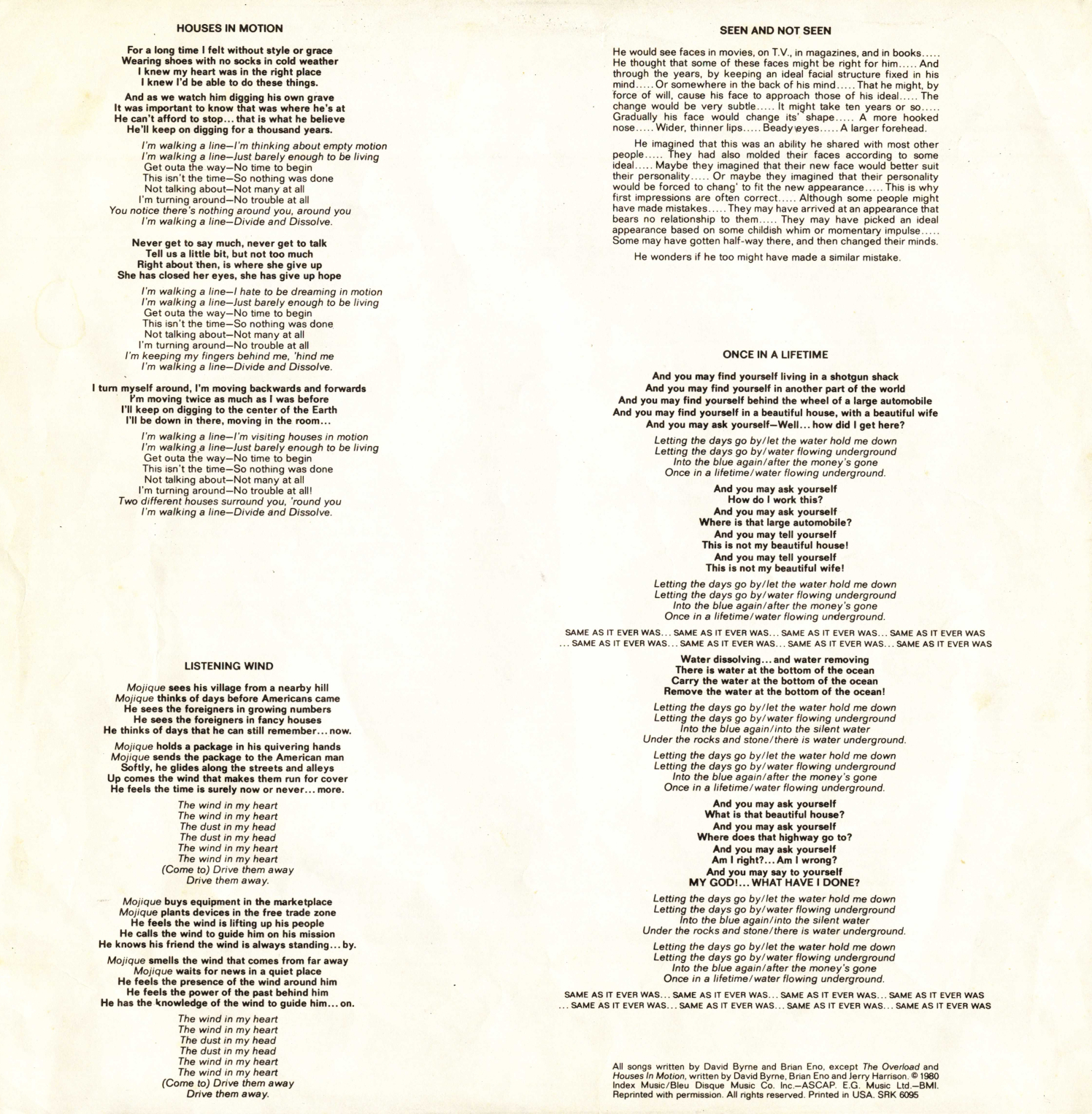

A curious aspect of the reissue business are the examples of when artists no longer include the lyrics that they once did include. For example, I was left perplexed and disappointed when the Hybrid C. D.-D. V. D. reissues of the Talking Heads studio albums (and subsequent reissues) did not include lyrics, though the original versions, especially in the L. P. format, made the lyrics very prominent. The display of David Byrne's lyrics in the first-third Heads albums had been typical of lyric sheets. Then came their fourth album, Remain in Light. Its lyric sheet presented the reader with an elaborate mix of fonts, alignments, and spacings, plus some playful experimentation with mechanics. The careful placement of the different parts of the songs: not only verses and chorus, but multiple bridges, or interludes, and, especially with the overlapping vocal parts of the three songs on the album's A side, mantra-like additional refrains—helps the listener make aural sense out of the dense arrangements, again especially on side A. [This lyric sheet, front and back, is scanned and seen below at higher resolution than those found at Discogs and similar sites.]

First becoming familiar with Remain in Light by listening to a vinyl copy, and very often following along with the lyric sheet, I cannot imagine how my appreciation for this album, one of my favorites, would be different if I never had the lyrics right in front of me. At the same time, if you are like me and tend to read "creative" writing, and be overwhelmed by all that one wants to read, while tending not to write oneself, beyond the kind of "uncreative" writing on display here, one must ask oneself some difficult questions. If, as seems to be the case, I often do not care to know the words of songs, is that not because when I have read the lyrics closely, as in Remain in Light, I have decided, however indirectly, that they do not matter much relative to the singer's timbre and style or more broadly how the words fit into the overall music? I find it easy to reach the opposite conclusion, but is that not because I got to know those lyrics well while I was also getting to know the music? The situation with many other albums, for example, another of my favorites, Brian Eno's Here Come the Warm Jets, is reversed: realizing roughly a quarter-century after I first heard the album that there may be official lyrics, made available only in Japanese L. P. versions released in the late Seventies-early Eighties, is not likely to change my appreciation of the music. Despite the curiosity sparked by straining, and failing, to discern the words of the murkiest vocals on that album, such as ‘Needles in the Camel's Eye’ and ‘Driving Me Backwards’, once I have the possibly-official lyrics in front of me, I am intrigued for a moment, and that moment passes. Unless, of course, I were, at that moment, to decide to perform the music myself, making the shift from consumer to producer, from sentience to creativity... And we're back at that: Do It Yourself.

The scans at Discogs of the aforementioned Here Come the Warm Jets lyric sheets are not high-quality, and I do not own one of those precious Japanese "vinyls," so here are my transcriptions. From the first song, I begin to doubt that these are official versions. The attempts that can be found online at those numerous lyrics web sites at times seem more accurate.

‘Needles in the Camel's Eye’

As you know

Don't let it grow

They just give you one long glance

And you know

Let it show how things grow

Go there this time

And fight for your soul...

Birds of prey you're too much to say

No one can beat my destiny

No matter why it lay

Why ask why

Oh why, oh why, oh why

Oh, mysteries are just like

Needles in the camel's eye

--

‘The Paw Paw Negro Blowtorch’

My, my my

We're treating each other

Just like strangers

I can't ignore

The significance

Of these changes

But you can treat it so lightly

And you have to face the consequences

All my worst fears are grounded

You have to make the choice

Between the Paw Paw Negro Blowtorch

And me

By this time

I got to looking for

A kind of substitute

I can't tell what I found

Except that it rhymes with "dissolute"

I may be so lazy

But she is almost unable

And it's driving me crazy

And her loving's just a fable

That we sometimes try with passion

To recall

Send for an ambulance

Or an accident investigator

He's breathing like a furnace

So I'll see you later alligator

He'll set the sheets on fire

Ooh, brighter, burning fire

So and so appears

Just another runner

You have to make the choice

Between the Paw Paw Negro Blowtorch

And me

--

‘Baby's on Fire’

Baby's on fire

Better throw her in the water

Look at her laughing

Like a heifer to the slaughter

Baby's on fire

And all the laughing boys are bitching

Waiting for photos

Oh the plot is so bewitching

Rescuers row row

Do your best to change the subject

Blow the wind, blow, blow

Let's have assistance to the object

Talk of the snip snap

Take your time

She's only burning

This kind of experience

Is necessary for her learning

If you'll be my floatsam

I could be hotter than I used to

They said you were hot stuff

And that's what baby's been reduced to

Juanita and Juan

Very clever with marracas

Making their fortunes

Selling their second-hand tobacos [sic]

Juan dances at Chico's

And when the clients are evicted

He empties the ash-trays

And pockets all that he's collected

But baby's on fire

And all the instruments have gone flat

--

‘Cindy Tells Me’

Cindy tells me

That rich girls are leaving

Cindy tells me

They've given up sleeping alone

And now they're so confused

By their new freedoms

And she tells me

They're selling up their masionettes

Let the hot ones

Rust in their kitchenettes

And they're saving their labour

For insane reading

Some of them lose

And some of them lose

That's what they want

And that's what they choose

It's a burden

Such a burden

Oh what a burden

To be so relied on

Cindy tell me

What do they do with their lives

Living quietly

Like labourers' wives

Perhaps they'll re-acquire those things

They've all disposed of

--

‘Driving Me Backwards’

Oh....out there

Oh, driving me backwards

Kids like me

Got to be crazy

Nobody thought

You must live and you can

Meet my relations

All are there

Grinning like face-packs

Oh sweet inspirations

Looking at us if you can

Now I've got a speed on

Treats me good

Just like an armchair

I try to make out I love you

But you know I'm mostly temperamental

I may be able to help you

To become so sentimental

I'll do it many times

I'll give it a try...

It's driving me crazy

--

‘On Some Faraway Beach’

Given the chance

I'll die like a baby

On some faraway beach

When the season's old

Blindly I'll be remembered

As the tide brushes sand in my eyes

I'll drift away

Cos what does it matter

We hope this will never be

A single silver ball

Oh, all that I know

La, la, la....

--

‘Blank Frank’

Blank Frank

He gives the messages

Of your doom

And your destruction

Yes, he is the one

Who will set you up as nothing

He is the one

Who will look at you side-ways

He'll take you quite skillfully

Maybe parked in people's drive-ways

Frank has memory banks

As cold as an ice-berg

He only speaks when he wants

And that's the whole problem

Blank Frank is the siren

He's the air-raid

He's the crater

He's on the menu

On the table

He's the wine man

He's the waiter

--

‘Dead Finks Don't Talk’

Oh cheeky, cheeky

Oh naughty, naughty

You're so perceptive

And I wonder how you knew

But these finks don't walk too well

A bad sense of direction

And so they stumble around in 3's

Such a strange collection

I was a headless chicken

Can this poultry

Take so much kicking

You're always so charming

As you go away again

But these finks don't dress too well

No discrimination

To be a zombie all the time

Requires such dedication

Oh please sir

Do you let a girl ride

Cos I failed both tests

Cos my legs were both tied

In my place

The stuff is all there

I've been ever so sad

For a very long time

My my my they wanted the works

Can you this and that

I never got a letter back

More fool me

Bless my soul

More fool me

Bless my soul

Oh perfect masters

They thrive on disasters

They all look so heartless

Till they find their way up here

Dead finks don't talk so well

They've got a shaky sense of diction

It's not so hard living here

It's just a dying fiction

--

‘Some of them Are Old’

People come and go

And forget to close the door

And leave their stains and cigarette butts

Trampled on the floor

And when they do

Remember me, remember me

Some of them are old

Some of them are new

Some of them will turn up

When you least expect them to

And when they do

Remember me, remember me

Lucy, you're my girl

Lucy, you're a star

Lucy please be still

And hide your madness in a jar

But do beware

It will follow you

It will follow you

Some of them are old

But if you could smile

To all the crooked sixpences

And many crooked miles

Because you do

Remember me, remember me

--

‘Here Come the Warm Jets’

We know when to come

But we know when to leave..

All these days

When we were down on our knees

Down on our luck

And we are learning to live...

–Justin J. Kaw, November 2022