The Byrds, Over- and Under-Rated

The Byrds, Sweetheart of the Rodeo

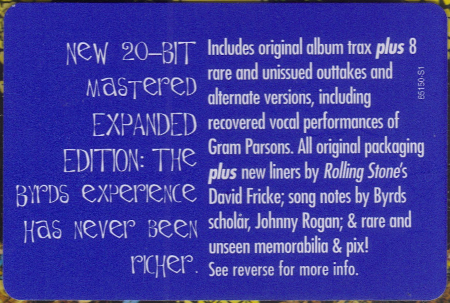

Originally released 1968, reissued 1997 (Discogs) with eight bonus tracks

Many of us avid listeners of popular music keep a running list of over-rated albums, or artists, in the back of our minds. Not wanting to rain on parades, we hesitate to write it out, save it for conversations, debate. Sweetheart of the Rodeo, the sixth Byrds album, is one that very likely would sit very close to the top of mine, lauded and dissected, I argue, largely because it is the single Byrds album to feature Country-Rock pioneer Gram Parsons. That said, the term, over-rated, with its grammatical awkwardness and conceptual ambiguity, pesters me. What is the over-rated album rated over? Other albums of course. Which albums? Most of all, in this case, its predecessor, The Notorious Byrd Brothers. This makes the hosannas that come Sweetheart's way more problematic still, because if anything Brothers after a half-century is still under-rated. It has its advocates, but they are not plentiful enough. Perhaps its title and cover art has mislead listeners over the years, expecting what they would get from Sweetheart, instead of the Psychedelic Folk-Rock (with a tinge of County and Western and a dash of what come to be known as Progressive Rock) that Brothers offers. More on the pleasures it offers in a moment—for now, a glimpse into the Rock-critic madness that allowed this unfortunate backwardness in Byrds appreciation to develop.

For, I hope that those still certain that Sweetheart out-ranks (up-ranks?) Brothers would nonetheless experience the same confusion I felt when reading David Fricke's untitled essay found in the liner notes of the 2003 two-disk Legacy Edition of the album. He writes, “Sweetheart of the Rodeo is now recognized as one of the Byrds' greatest triumphs, among the most important and prophetic albums ever made, because we would have so little modern pop without it: the cosmic-cowboy and singer-songwriter movements of the 1970s; the 1980s roots-rock and paisley-jangle revivals; the parallel rise, in the 1990s, of a pop-wise, platinum-smart Nashville and the rugged sincerity of alternative country. In sales and celebrity, Poco, the Burritos, the Eagles, Crosby Stills and Nash, R. E. M., Wilco and the Dixie Chicks - to name just a handful - owe a huge debt to the Byrds and Sweetheart of the Rodeo.” What is going here? A few seconds after reading that mouthful, my reaction was: are you talking about the Byrds overall? or just this one album? The last sentence credits both, as if Fricke realized his hyperbole had gone haywire. That's when you edit, Fricke. What do the Paisley Underground bands have to do with Country-Rock? And the singer-songwriter Soft Rock of James Taylor, et al., would have done nicely with or without a single Byrds album (Joan Baez was “ready for the country” in 1968 too). As had been stated and re-stated so often that you could think we are all living in an four-walled eternity plastered with clippings from Mojo magazine, the standard Byrds sound heard on their first four albums, as well as Brothers (which Peter Buck of R. E. M. singled out as especially influential on him) was the commanding influence on a certain 1980s “jangle” sound marked by the 12-string electric guitar. Fricke seems to position Sweetheart's Country-Rock as a culmination of that material, even as he then spends the rest of the essay discussing how different the album is from the band's first-fifth albums. Why are statements that would make unscrupulous advertisers blush considered de riguer in the Rock nostalgia trade?

Beyond his self-parodic effusive praise for the album, Fricke's essay at least provides most of what the listener needs to know about its origin and greatest moments: for example, starting recording in Nashville, winter 1968, the Byrds encouraged pedal-steel guitarist Lloyd Green to craft a free-floating contribution to the Bob Dylan's ‘You Ain't Goin' Nowhere’, one of the “Basement Tapes” songs that had yet to be heard by the general public; Green is quoted contrasting the experience with the “regimented” nature of standard Nashville sessions. Other Nashville musicians participated in the sessions: Earl Ball played the piano, John Hartford the banjo and the fiddle, Roy Husky the double bass, Jay Dee Maness the pedal-steel, and Clarence White the guitar (White had played on the Byrds track ‘Time Between’, bass guitarist Chris Hillman's choice as the first Country-Rock song, on Younger than Yesterday, plus several tracks on Notorious, and would soon join the band as Gram Parsons' replacement).

As Fricke explains, Parsons, a new convert to Country and Western, had been invited to audition for the Byrds by Hillman, and in turn briefly (almost) took over the band. Roger McGuinn and Hillman were the two remaining original members. Kevin Kelley had replaced drummer Michael Clarke, who had left at the end of the Notorious sessions, but the band also needed a second guitarist, and ideally another singer: David Crosby had been left early in the Notorious sessions. The Byrds as a trio had worked fine in the studio but was not a long-term solution: a whole different set of first-rank session musicians, from Los Angeles (the “Wrecking Crew”) instead of Nashville, had filled out Notorious. And the band needed to get back on the road, having never quite proven themselves as a live act, at least not since their famous residency at Ciro's in Los Angeles, 1965. Parsons, with his “golden tongue” and youthful enthusiasm, got the job. In turn, Hillman, who had grown up with the music and had played it pre-Byrds, joined Parsons in encouraging McGuinn to let the Byrds go full-on Country and Western.

With Hillman taking the lead on two songs and McGuinn only doing two Dylan numbers, premiering another of Dylan's Big Pink songs, ‘Nothing Was Delivered’, and covering a Woody Guthrie tune (‘Pretty Boy Floyd’), Parsons filled in the rest. At least initially. Situations conspire: Lee Hazlewood, who had released an album by Parsons' previous act, the International Submarine Band, claims some sort of contractual right to Parsons' work; Parsons supposedly objects to the band playing in racist South Africa, actually befriends Mick Jagger, who purportedly encourages him to form his own band; McGuinn replaces two of Parsons' lead vocals; Parsons launches the Flying Burrito Brothers, then goes solo, helps launch the career of Emmylou Harris, and dies in 1973 from typical childish debauchery; history is history. So what really happened to the Byrds in 1968? Regardless of some of his lead vocals being replaced, Parsons determined the content of an album by one of Rock's biggest bands to a greater extent than the band's leader McGuinn and the other remaining original member, Hillman, a striking achievement for a young buckaroo—or, rather, a telling sign that the Byrds nearly fell apart entirely. After Sweetheart, McGuinn, having seen bandmates fall over like dominoes for two years (Gene Clark, Crosby, Clarke, Hillman—who soon enough joined Parsons in the Flying Burrito Brothers), assembled a new version of the Byrds that would prove more stable, by a hair, and certainly more capable as a live act, than the famous first version. Besides Clarence White, drummer Gene Parsons (no relation to Gram) would also stay to the end, with John York playing bass on two albums, Skip Battin on three.

In other words, is Sweetheart a masterpiece, or merely a surprisingly-good one-off experiment that also served as the transition from Byrds I to Byrds II? Listening to the album closely and as a whole, the answer is plainly the second option. Granted, the album features two performances that rank among the Byrds' best: the aforementioned ‘You Ain't Goin' Nowhere’ and ‘Hickory Wind’. The latter, which Parsons co-wrote with former Submarine Band-mate Bob Buchanan, gifts us one of his finest vocal performances. Parsons also excels on his other unaltered lead vocal, ‘You're Still on My Mind’. McGuinn and Hillman added vocals to ‘One Hundred Years From Now’, originally a Parsons lead, substantially improving the song, which offers fine performances from all involved. Beyond these four tracks, the waters get choppy. The album's devoutest acolytes would have preferred Parsons' original lead vocals on ‘The Christian Life’ and ‘You Don't Miss Your Water’. McGuinn's Parsons imitation on the former is slightly embarrassing. He tackles ‘Water’ more seriously, but his voice simply does not fit the song like Parsons' does. The Nashville pros provide a fine instrumental backdrop to ‘I Am a Pilgrim’ and ‘Blue Canadian Rockies’ (Hillman's two lead vocals) and ‘Pretty Boy Floyd’, but the vocals and the melodies they deliver do not amount to much. Finally, the second Dylan-“Basement Tapes” tune, ‘Nothing Was Delivered’, seems like a shallow attempt to repeat the success of the ‘You Ain't Going Nowhere’.

One matter left unclear by the liner notes: ‘Life in Prison’'s lead singer, who is, in fact, Parsons. It undoubtedly began as a Parsons lead. Parsons sudden decision not to perform the song (in favor of ‘Hickory Wind’) during the band's performance on the Grand Ole Opry radio program was apparently controversial (because, says Fricke, of the mere fact that the song was switched after the broadcast had started, “an unpardonable crime”—more Rock-critic phony gravitas?). In the Legacy Edition notes, Fricke says that only Parsons' vocals on ‘You're Still on My Mind’ and 'Hickory Wind’ were “untouched” after Parsons' exit. In his notes for the 1996 C. D., Fricke claimed ‘Hickory’ and ‘One Hundred Years’ had not been changed, while Rogan said ‘Hickory’ and ‘You're Still on My Mind’ (yes, the same reissue offered two historical revisions). Part of the confusion would seem to stem from Parsons' vocals in some cases remaining in the mix, but being pushed into the background to make room for the new McGuinn leads; this is the case at least on ‘You Don't Miss Your Water’, according to Tim Connors, author of the Nineties-vintage website Byrd Watcher (sadly defunct, but available via the Internet Archive). Either way, the C. D. reissues include the Parsons-lead versions of ‘The Christian Life’, ‘You Don't Miss Your Water’, and ‘One Hundred Years From Now’, on the first disk no less, allowing the listener easily to program an alternate version of the album in his C. D. player, reflecting the apparent original intention of having six Parsons lead vocals out of 11 total tracks. One cannot help but conclude, however, that history is not always yet, fully, history: that even if Parsons had not left the band, the newer ‘One Hundred Years From Now’ would have still replaced the earlier. It came from the Los Angeles sessions in the spring of 1968 that followed the Nashville sessions; Parsons was still in the band. Was McGuinn already justifiably concerned about Parsons' presence on the album being too dominant? Retrospective reviews seem to think we can avoid this matter, as if the formal content of an album is not precisely what the critic is discussing but is rather—shall we say—a glitch (an appropriate digital-era term) in the album's reception history that can be ignored.

In the end, Sweetheart certainly is more historically, than artistically, significant. It is a landmark: the beginning of Country-Rock. It inspires because of what it suggests could be accomplished in the future, not for what it has already accomplished. ‘You Ain't Going Nowhere’, ‘Hickory Wind’, ‘You're Still on My Mind’, and ‘One Hundred Years From Now’ rank as essential Byrds tracks, those which a novice would need to hear to understand the curious transitional phase of the band's history embodied by the album as a whole. That first Submarine album (released earlier) and the Beau Brummels album Bradley's Barn (released a few months later) did not generate enough interest at the time (or now), perhaps unfairly so. And Baez wasn't Rock enough. That said, I have never seen, nor do I expect to see, anyone claim that Sweetheart is more historically significant than ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’. In that sense, Sweetheart is second-rate after all. Moreover, in its piecemeal production and halting flow, it pales in comparison to Brothers. In the same way, it is also inferior to Music From Big Pink, the Band's debut (released nearly two months prior), generally not considered to be County Rock, which means: a richer stew of sounds and styles, devoid of the mannered “Southern” accents that make so much Country so very gauche; perhaps a bit lugubrious at times, but at least lacking the herky-jerky jumps from synchronized-dancing rhythms to drawling ballad pace that makes Country, for me, at times too grating of a listening experience. Having said all that, the album does not take us back to the inconsistencies of the first-fourth Byrds album; that is, it does not have what we would commonly call filler. There are no duds, beyond McGuinn's misguided vocal on ‘The Christian Life’.

The steady rise to commercial prominence of “alt Country” and “Americana” relative to Rock-and-Roll in the Twenty-First Century has arguably made the likes of Fricke forget that most Country and Western pales in comparison to Rock. Let's not forget that. Put on Brothers after listening to Sweetheart. It has the supple rhythms that Rock gets from Jazz and its popular-song child, Rhythm and Blues; and the experimentation with form that Rock, a bastard birthed from stolen bits of other musics, requires to continue being its uprooted self. The notion that the best, most important, Byrds album is a Country-Rock album? And, moreover, one that developed by fortunate, if jumbled, happenstance and was botched by legal and personnel problems in its construction? Ridiculous. (As explained below, the personnel problems experienced during Notorious, in contrast, had a positive effect for that album.)

An unfortunate aspect of the Legacy Edition: the decision to include a selected number of International Submarine Band tracks: three of the nine tracks from the band's aforementioned first album, Safe at Home [1968], both sides of the band's second 45 (‘Sum Up Broke’ b/w ‘One Day Week’) but only the B side of the first: ‘Truck Drivin' Man’; the A-side track, ‘The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming’ has currently been relegated to the Sundazed label's vinyl reissue of Safe at Home, with includes the first 45 (but not the second!) as a bonus. An earlier Sundazed C. D. version of the album included none of the four single-only tracks, instead offering a bonus track, ‘Knee Deep in the Blues’. In short, if you combine the two-disc Sweetheart with the vinyl reissue of the International Submarine Band album, you get the original published output of the first version of the Submarine Band (it was revived in alternate form in the late Nineties-early Aughts) except ‘Knee Deep in the Blues’; obviously, preferably the Submarine material would be in one place.

The Byrds, The Notorious Byrd Brothers

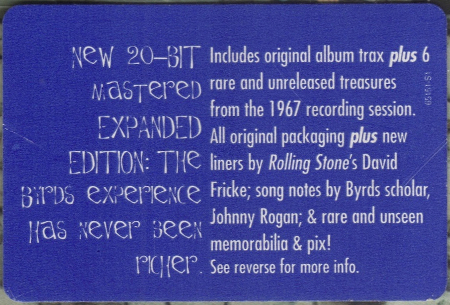

Originally released 1968, reissued 1997 (Discogs)with six bonus tracks

Reading David Fricke's liner notes for the C. D. reissue of The Notorious Byrd Brothers, we learn what stops too many from granting The Notorious Byrd Brothers its proper place as the greatest Byrds album: to quote, “Notorious is dated by a handful of period-production touches that place it squarely in the immediate post-Sgt. Pepper era.” For the most part, Fricke seems to have kind words for the electronic effects used in the album, and for the producer, Gary Usher, who crafted many of them. Of course, he generously receives all of the Byrds albums in his essays written for these reissues; he is being paid to do so. Critics in such situations, especially those like Rock critics generally not ranked highly as writers or independent thinkers, must make their presence known, add a caveat or two. At that point, the received wisdom, stock phrases and talking points, well-worn demeanor, and well-rehearsed showy attitudes that, in varying combinations, comprise the calling cards of Rock journalists come into play. So we get that “dated” tag, more like a Rolling Stone-mandated nervous tic than an opinion reached by a sentient person. "Dated," of course, suggests the failure of the album to live up to a standard of timelessness that we are left to suppose every critic must employ. One would have thought that, by the time these reissues appeared, the Neo-Psychedelia of the Flaming Lips, Ghost, et alia would have put to rest the notion that certain manipulations of recorded sound used in Rock songs are always to be associated with a few years in the Sixties. The larger problem comes from the implied claim that a work of art being obviously tied to—directly suggesting in its content—the era in which it was created somehow works against its later relevance. This claim is sheer nonsense. How do advocates of this position handle visual-art movements that flared briefly, like Fauvism, which cannot be divorced from a period of only a few years in the development of painting?

Proper recognition of this album comes from Ric Menck, the author of the album's entry in Continuum's 33-1/3 book series (each book being a long essay about an album). Co-leader and drummer of the band, Velvet Crush, Menck's book includes personal reminiscences about his own discovery of the album, as well as accounts of his limited encounters with McGuinn and Hillman. He also states baldly that Notorious offered “one of the most profound listening experiences of my life,” that it is “like walking through an unimaginably beautiful waking dream.“ I hesitate to share such strong sentiments, even as the album has been a favorite of mine for roughly twenty years. But then he describes the album's strong suit perfectly: “disparate elements all combined into one singular organism that seemed to be constantly evolving from one song to the next.” Indeed, the segues from one track to the next only occasionally seem forced or after-the-fact, making the eleven tracks flow together to form a whole, as if the particular order in which they play on this album was the only configuration that could fit them, the only larger form that the individual songs could possibly take.

Menck's review of the album, track by track, reiterates this dominant characteristic of the album and often effectively convey their brilliance. Referring to ‘Natural Harmony’: “the music and lyrics combine to conjure a cinematic response [...] creating little ‘mind movies’” so that the album “seems more like the soundtrack,” a sensation obviously heightened by the tracks being linked together. When he turns to ‘Wasn't Born to Follow’, Menck again discusses the album as “one long, continuous piece of music,” highlighting Usher's influence. Also the instigator of the experimental studio-centric band Sagittarius, Usher brought with him a wealth of ideas for expanding the sonic palette and compositional methods of popular song when he worked as a producer: two Chad and Jeremy albums that he helmed, Of Cabbage and Kings and The Ark, were similarly tracked seamlessly to make a singular piece of music. Usher also convinced McGuinn to record ‘Wasn't Born the Follow’, a Gerry Goffin-Carole King song, having already convinced the band to record another Goffin-King, ‘Goin' Back’, the inclusion of which led to David Crosby to quit the band in anger. In other words, Usher not only helped the band get rid of the arrogant, petulant Crosby but also introduced the band to the song that would, for better or worse, become their last “classic” recording when it made its way into the film Easy Rider nearly a year after its release; indeed, a song of great significance to its time and its early listeners, its title alone capturing the unifying message of an entire generation of young persons. Menck describes this track perfectly: after noting the dense but delicate arrangement of several guitar parts and its gentle Country beat, he says, “what sets the song apart is the middle section [...] where the band locks into a one-chord drone that pounds with the intensity of a garage rock band, and McGuinn explodes into a searing guitar solo. [...] At the same moment that McGuinn's solo begins, Usher slams the entire track through his compressors, and the track sounds like it's being sucked into some strange time/space continuum,” only to have Usher's effects takes us back down again to the song's basic form for a quick conclusion.

Discussing ‘Get to You’, the brilliant McGuinn song that closes side A, Menck acknowledges McGuinn's well-known aloof, at times disarmingly reserved, manner, an impenetrable distance between him, especially given his vocal Christian beliefs, and his listeners and even most of the music he recorded in the years, 1965-1979, that at least has had the benefit of making him anything but a prototypical aging Rock Star. ‘Get to You’ shows this “seemingly passive fellow [...] willing to reveal so much emotion.” Menck credits his background in Folk and Bluegrass, genres with a “direct line between the emotional content of a lyric and the singer's ability to deliver it with real sincerity,” but in this case, and with all of this album, specific aspects of the recording are arguably crucial. Menck makes note of these: the orchestral strings that follow McGuinn's singing of the melody but most of all the striking vocal arrangement during the song's refrain, though Menck only notes the “percussive,” breathy sequence of sounds one voice is making. With McGuinn singing, “That's a little better,” in a high voice that flies above the rest of the music, a vocable part offers the main part of the melody here. The interplay among these three serves as the pinnacle of the album.

Crosby's sudden departure during the album's production of course deserves further explanation. The single-disc “expanded” reissues (the terminology I use as compared to a double-disk “deluxe”/ “legacy”/ “collector's” or a boxed-set “super deluxe”) all include Johnny Rogan's song notes accompanying Fricke's essays. Thankfully, in this case, these notes prove quite helpful in dispelling any doubts one may have about this album and Crosby's exit. If I seem too harsh on Fricke, let me add his embarrassing praise for the David Crosby song, ‘Triad’, which expresses the narrator's desire for a romantic threesome with two women whose affection for him is condescendingly portrayed by the narrator in the naive-arrogant manner of the youthful, and the exclusion of which in favor of ‘Goin' Back’ apparently served as the decisive factor in Crosby's leaving the band: "Notorious would have been an even better album if had included Crosby's exquisite ‘Triad’"; he adds, “the come-hither lilt in Crosby's voice and the sprinkled-stardust effect of the guitars have lost none of their seductive charm.” Let me give you a moment to get some Listerine.... and explain: Jefferson Airplane eventually recorded ‘Triad’ for their fourth album, Crown of Creation, saving it from obscurity, and saving Crosby from embarrassment by having Grace Slick do the lead vocal, turning the table on Crosby's desire for fawning adoration. Though Crosby was a friend of the Airplane, and the band's rendition of the song was clearly respectful, Slick's purposeful complication of the theme had the unintended result of exposing Crosby's hyperactive desire for recognition, and want to party, for what it was.

Crosby's diminished role helps elucidate how Notorious does not quite fit in with the first-fourth albums (that is, the trademark Byrds sound). If you do not share—please, please don't—Fricke's ridiculous love for ‘Triad’, the three Crosby-penned tunes on Notorious offer more than enough of the self-anointed Rock star: Crosby had put aside the formal experimentation of some his earlier songs, like ‘Mind Gardens’ on the band's previous album, Younger than Yesterday, in favor of simple sketches of songs more fitting for a composer still on his training wheels. These sketches in turn were finished by the band without him, most likely a good thing, as ‘Triad’ (included in its original Byrds version on the 1997 C. D. as a bonus track) shows well enough that Crosby as a lead vocalist was still nowhere near what he would pull up from the personal and stylistic depths on If Only I Could Remember My Name, his dark but beautiful 1971 solo album. The three songs, ‘Draft Morning’, ‘Tribal Gathering’, and ‘Dolphin's Smile’ serve as exemplary deep cuts. They provide thematic links to other songs, especially ‘Wasn't Born to Follow’, the lyric of which complements the doubts suggested in ‘Draft Morning’; ‘Change Is Now’, which can be seen as a follow-up to ‘Tribal Gathering’; and ‘Goin' Back’, which to an extent looks nostalgically upon the "childhood's dream" evoked in ‘Dolphin's Smile’. While Rogan notes Crosby's influence of the album's vocal arrangements, Crosby's lead vocals do not dominate the foreground of these three songs in the way he did on ‘Mind Gardens’ or ‘Everybody's Been Burned’ (also on Younger)—and according to Tim Connors, Crosby's vocals did not make the final cut of ‘Draft Morning’. And in general, harmony vocals are not as prominent as they were on the first-fourth albums, especially because they are often processed through various effects.

With standard Folk stylings and Crosby's vocal presence both minor, McGuinn comes to the fore. Indeed, the simpler reason why Notorious is the best Byrds album is that, alongside (Untitled), it offers the best selection of original Byrds compositions; granted, that decidedly is not the same thing as the best selection of songs generally, given the important place that traditional folk songs and covers occupy in the Byrds discography. Nonetheless, instead of the separate composers pushing the album in multiple clashing directions, as had been the case with the Byrds until now, all of the songs of Notorious, even without the electronic effects that wash their colors together, seem to bear the mark of McGuinn, now the undisputed leader of the band. ‘Artificial Energy’ (credited to McGuinn, Hillman, and Clarke), ‘Get to You’ and ‘Change Is Now’ (both credited to McGuinn and Hillman), and ‘Space Odyssey’ (with lyrics co-written with Robert J Hippard based on the Arthur C Clarke story, ‘The Sentinel’) are obviously thought of as McGuinn songs, though Hillman played a crucial role in composing ‘Artificial Energy’ at least. The two Goffin-King tunes, ‘Goin' Back’ and ‘Wasn't Born to Follow’, are also showcases for him. The gradual rise to “classic” status of Sweetheart of the Rodeo, where McGuinn took over two Gram Parsons lead vocals that ideally would have been left alone, beclouds an important facet of the post-Crosby Byrds: the music was better when McGuinn sang lead—again, with the exception of those two Parsons songs. Consider the subpar vocal performances of John York and Clarence White in the later version of the band.

Like most Byrds albums, and especially so in this case, figuring out who played and when on this album requires further dissection of the recording process. Since Menck's book, like many of the 33 1/3 books that I have read, does not excel in providing citations (that is, it provides none) we rely on Tim Connors' old website to confirm details. We can start by putting ‘Space Odyssey’ aside, as it apparently featured only McGuinn and Usher, on the same day (October 23rd) that they did ‘Moog Raga’, included as a bonus track on the 1997 C. D. That leaves 10 tracks. Both Crosby and Clarke each play on four and these two sets of songs mostly over-lap: that is, Crosby plays on his own ‘Tribal Gathering’ but Clarke does not, while Clarke is on ‘Artificial Energy’ (December 5th-6th) but Crosby had quit the band by that point. Another way of putting this: ‘Old John Robertson’ (June 21st), ‘Draft Morning’ (July 31st-August 3rd), and ‘Dolphin's Smile’ (August 14th) were recorded by the quartet that the Byrds were when the album sessions began. A bitter argument that took place while recording ‘Dolphin's Smile’, with the other three members losing their patience with Clarke's inability to meet their demands for the song, led to Clarke's temporary exit. “Wrecking Crew” drummers Jim Gordon and Hal Blaine took his place on ‘Tribal Gathering’ (August 16th), ‘Get to You’ (August 30th), ‘Goin' Back’ (October 9th, 11th, and 16th), ‘Natural Harmony’ (November 29th-30th), and ‘Wasn't Born to Follow’ (November 29th-30th), and likely the final mix of ‘Dolphin's Smile’ as well. Clarke would return for ‘Change Is Now’ on August 29th and 30th (Menck notes it had already been attempted a month earlier, so perhaps Clarke was grandfathered in for the song) but would not retake his drummer throne until the very end of the album's sessions, for ‘Artificial Energy’. Soon enough, though, he was an ex-Byrd as surely as Crosby. (At least part of the fiery exchange among the band members during the recording of ‘Dolphin's Smile’ is included as a hidden track on the 1996 C. D., beginning 6 minutes and 41 seconds into the final track of the disc, perhaps the most absurdist bonus track ever included on a reissue.) As with Crosby not wrapping up his own songs, the use of multiple drummers, even as it indicated the original version of the Byrds coming apart, ultimately gave Notorious a rhythmic complexity that the Byrds lacked to this point. Drums and cymbals pierce through to the forefront of the mix several times throughout the album, especially in providing the segues at several points.

Indeed, as with Sweetheart, session musicians like Blaine and Gordon played an important role in this album. Unlike Sweetheart, the producer, Usher (he was at the helm for both albums), was even more important. For example, as McGuinn complained that the horn players on ‘Artificial Energy’ played too “straight,” Usher subjected them to the same electronic treatments that the vocals received on the track, resulting in a high-pitched, nasal sound on the latter, and a brittle, disorienting choppiness to the former. A session musician, Paul Beaver, plays a big role in ‘Natural Harmony’ but he plays the synthesizer, and its sounds work well in tandem with Usher's heavy effects... one hardly even notices that Hillman, who composed the song, is on lead vocal. The Firesign Theatre made an invaluable contribution to ‘Draft Morning’, in the form of an aural collage of war-related sounds. The aforementioned interlocking guitar parts of ‘Wasn't Born to Follow’ saw McGuinn joined by Clarence White and Orville “Red” Rhodes, the latter on the pedal steel, which he also used to considerable effect on ‘Get to You’; that said, all of White's and Rhodes' contributions tend to get lost in the mix. Even with the string section that pops up suddenly on ‘Old John Robertson’... whereas on the original version, released as the B side to the non-L. P. 1967 single ‘Lady Friend’, the strings were unadorned, here Usher again uses spatial panning to give the entire song an otherworldly feel. When McGuinn finally offers guitar solos, on ‘Change Is Now’ and ‘Tribal Gathering’, there too the final electroacoustic sound of the guitars, after their sound has been manipulated by Usher, comprises the content of the solos as much as what McGuinn's fingers are doing.

Notorious stands as Usher's finest achievement. He excelled as a producer and, in the case of Sagittarius, a ringleader of sorts for multifarious, perhaps not always complementary, personalities. The first Sagittarius album, Present Tense, as delightful as it is, hardly holds together like Notorious. For many Byrds aficionados, and presumably for the Rolling Stone-approved dogmatists of commercial success, the notion that the best Byrds album was both a flop in the marketplace and yet commands attention because it was the peak of the career of a relatively-obscure figure in 1960s Rock simply cannot be true. As Fricke hints, even if only subconsciously, a “dated” album cannot be the band's best. But it is. It is the "dated" nature of Usher's electronic effects that distinguishes the album. And for a band pushed by Columbia Records to release too much product, resulting in slapdash collections of songs, the relative uniformity of sound combined with the widest range of talent ever to work on a Byrds album made for the best Byrds album. It is both a pleasure to listen to in its entirety and an historical landmark.

–Justin J. Kaw, January 2020

Sometimes the B Side Is Just That: B-Grade. A Never-Ending Serial

The Byrds, Mr. Tambourine Man

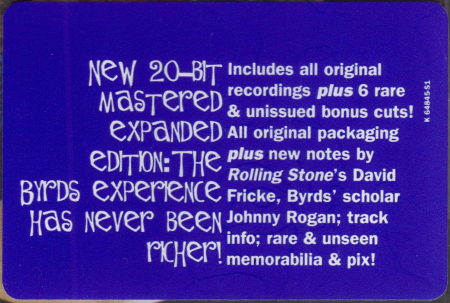

Originally released 1965, reissued 1996 (Discogs) with six bonus tracks

The debut Byrds album shares an important trait with numerous other Sixties “classic” albums: critics and fans breathlessly announce the presence of genius and make bold claims for an album's integral quality, blatantly ignoring certain facts obvious to even the casual listener. These facts, in the case of Mr. Tambourine Man, are that the album was completed in a rushed, haphazard fashion, few popular-music artists were conceiving of album as cohesive works of art circa 1965, and many of these critics and fans clearly seem to be evoking a track or two rather than most of the album's deep cuts. In his liner notes to the 1996 reissue, David Fricke for once differs from received wisdom, indirectly capturing the album's ambiguous place in the Byrds oeuvre when he makes quite a jolting switch from a harsh summation: “one hit single and eleven afterthoughts," to a generous re-take: “an impeccably crafted declaration of talent"—within the same paragraph no less. This flip-flop is a more accurate reflection of what countless listeners in the past half-century have experienced when listening closely to this album, which starts so well with the band's legendary cover of Bob Dylan's ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and the quintessential Gene Clark tune ‘I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better’ but concludes with several desultory tracks on the B side weighing the whole thing down. Contrast those two quotes from Fricke with Richie Unterberger's review for the All-Music Guide, which begins: “One of the greatest debuts in history of rock.” Granted, that statement may have been true in 1965, but of course this is a retrospective review, like most at the All-Music Guide. The album, Mr. Tambourine Man is not one of the greatest debuts, the single, ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’, is. Why is this distinction so hard to make?

Nonetheless, the album coheres somewhat well. The year, 1965, is almost as good as any marking point (1967? 1971?) for the beginning of the album era and this album compares with other great albums of that year that seem to be crawling toward the destination that we have, with the benefit of time, divined for it: the “classic” album, great from start to finish, that takes the listener on a journey. The band's unique overall sound forms a crucial part of the picture. Fricke quotes a 1968 Rolling Stone article by Jon Landau, where the critic (later to become a Bruce Springsteen sycophant—excuse me, “producer”) rightly praises the singular, consistent style of the Byrds, crafted as it was out of disparate influences and by clashing personalities, all of which could have easily turned the first-fourth albums, which most of all are marked by that style, into slipshod affairs; instead they are of piece: decent albums cobbled together too quickly and undermined by occasional filler, but overall at least offering more highlights and ideas for the future than nearly every other group in 1965-early 1967 except the Beach Boys and the Beatles and of course the major exception, Bob Dylan. As for that singular sound of theirs, while it is not exactly a “wall of sound,” it offers a dense canopy: Clark's tambourine helping out drummer Michael Clarke's basic beats; two-part harmonies sung by three singers, some of whom may be double-tracked, often forming a hazy layering of vocal sounds; and two guitars, one of course McGuinn's famed 12-string Rickenbacker electric, plus Hillman's precise bass contributions, pleasantly interweaving.

The tag, Folk-Rock, used to describe this signature Byrds sound and its numerous followers, according to Fricke “never did justice” to the band. But what genre designation does? In my own estimation, any listener can usually distinguish vintage Folk-Rock by asking if the vocals and guitars, minus the bass and drums, would have fit in well enough with the Folk Revival style of the time. Rhythmically speaking it is hardly sophisticated. The prototype Folk-Rock sound is perhaps the electric version of Simon and Garfunkel's ‘The Sound of Silence’, released in September, 1965, since it originally had been an vocal-and-acoustic guitar number, with producer Tom Wilson adding electric guitars and drums later, making for somewhat of an awkward backing track but nonetheless leading to a result that, like alchemy, elevated the two constituent parts, Folk and Rock, into something grander.

One theme common to many writers on the topics of the Byrds and Folk-Rock is that of the Byrds not receiving sufficient credit for the extraordinary shift represented by their version of ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’—that is, for the Folk-Rock phenomenon. First, Folk guitar and vocal skills were dearly needed by Rock-and-Roll circa 1965: the British Invasion and what we would call its reactant American Explosion (the music generally called Garage Rock) were bound to run aground eventually, hampered by their derivative relationship with Rhythm and Blues/ early Rock-and-Roll that preceded it. Second, Folk-Rock encouraged song composers to work on their own, not only in place of the Folk Revival standard of adapting other composers' or traditional songs, but also instead of working out songs during band rehearsals. Richie Unterberger, as noted above, is a big fan of this album; the good news being that he has written two excellent books on Folk-Rock. In the first book, Turn! Turn! Turn! The '60s Folk-Rock Revolution, he discusses these positive effects. He quotes Gary Marker (a member of the Rising Sons, a short-lived ensemble that also included Taj Mahal, Ry Cooder, Jesse Kincaid, and future Byrd Kevin Kelley) rightly claiming that American Rock, as compared to Rhythm and Blues, had seemingly reached its final stages, with innovators and stars that had emerged in what we could call the second wave of Rock (following the first, 1954-1957) having already made their biggest marks—Roy Orbison, Wanda Jackson, the Everly Brothers, numerous Surf Rock acts—and finding themselves overthrown by the Beatles. As conventional histories put it, the Byrds served as the major American response to the Beatles, hinting at but not quite stating directly that British bands would not feel as comfortable or even inclined to cover songs written by the likes of Dylan (or, jumping ahead a few years, Leonard Cohen or Joni Mitchell). Indeed, that would turn out to be true. Unterberger notes that the Byrds "gave fledgling songwriters hope," at the same time that they freshly inspired some of their fellow Folk Revivalists who had grown tired of protest songs or digging through the same old collections of folk songs hoping to find one that had not been done to death.

Thus a Byrds cover of a vocal-and-acoustic-guitar piece, ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ launched a style, or subgenre, Folk-Rock, that would up-end the entire Rock world. Dylan's original version is found on the B side of Bringing It All Back Home, the A side of which featured not Folk-Rock, just Rock-and-Roll. Dylan would continue that sound, brilliantly aided by musicians like Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper, Bruce Langhorne, and Charlie McCoy. While Dylan was the pivotal figure in inspiring other song composers to abandon well-worn subject matter and structures, he differed from many of this contemporaries, with the major exceptions of the Rolling Stones, in the continued influence of Rhythm and Blues in the sound that he crafted in the studio and in concert with the Hawks (who became the Band). Kooper's Blood, Sweat and Tears fits into this paradigm as well, and to a lesser extent other scattered bands. Overall, though, Rock and Rhythm and Blues were taking divergent paths. (For me, the turn toward Country-Rock nearly derailed Dylan. Want an example of an album that features a couple great tracks and a lot of filler? Look no further than Nashville Skyline. This was the prevailing opinion of the time—see: the very notion of a “new morning” or David Bowie's ‘Song for Bob Dylan’. As I argued in the essay about Sweetheart above, Country-Rock justly receives its due all these decades later, but it hardly deserves the zealous praise that contemporary Rockers embarrassingly gush all over it.)

Having said all that, let us not over-rate—that word again!—this album. What is consistent about it, as noted above, is the sound that the band collectively presents. The Byrds offered much more of a defined, unique approach than, say, the Searchers, the major British Invasion that covered Folk Revival favorites. (The very eclecticism suggesting a lack of unique vision—and ultimately little success after 1965—characterizing the Searchers also meant that their albums offered a wider array of sounds and styles, circa 1965, than those of the Byrds.) After ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’, three additional Dylan songs are included; all of them come from Dylan's fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan. Three is too much: the Byrds' ‘All I Really Want to Do’ is awkward, at best; ‘Chimes of Freedom’ works but it runs along Folk-Rock's major fault line: too staid for Rock, yet obviously tailored for the radio market in a way that most Folk Revival music was not. For me, ‘Spanish Harlem Incident’ fits in better: for a Dylan composition, it is sufficiently light-hearted to work as a pop ditty. Unterberger, though, claims, “Dylan would have never made ‘Chimes of Freedom’, ‘All I Really Want to Do’, and ‘Spanish Harlem Incident’ as gorgeous a listening experience”: not exactly the right word to describe the limited fidelity of Byrds recordings at this point in their career, and either way quite off-track for ‘Chimes for Freedom’, an exquisite Dylan performance and song that has illuminated the consciousness of many a listener over the years.

Listening to the album as a whole, I experience the transition from joy to boredom hinted at by Fricke's contrary summations when flipping from the A side to the B. In short, Unterberger and others who insist on the album's “classic” status make sense when listening to the A side, the first-sixth tracks. The B side by comparison is an afterthought, the difference showing through even in the rough recording quality of most of its tracks. A similar disjunction occurs again on Younger than Yesterday. There, the A side feature two songs apiece from McGuinn, Crosby, and Hillman. The A side of Tambourine features two Clark originals, McGuinn's versions of two Dylan songs and one folk song, and a McGuinn-Clark tune, ‘You Won't Have to Cry’, the first of several Beatlesque pieces that the Byrds proffered in their early days. The latter follows ‘Spanish Harlem’; both flow well enough, taking us to Clark's ‘Here without You’, which effectively counters the up-tempo, but cynical, ‘Whole Lot Better’ with a slower-paced, wistful look back upon lost love. The folk song, the first side's concluding track, ‘The Bells of Rhymney’, constructed by Pete Seeger out of a Idris Davies poem, was apparently brought to the band by McGuinn, who takes the lead, both singing and in a brilliant concise guitar solo that ranks with the introduction to ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and the guitar solo on ‘Eight Miles High’ as an exemplary McGuinn-on-the-Rickenbacker moment.

Clark's only solo composition on the B side, ‘I Knew I'd Want You’, had itself been the B-side to ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’, which means that it too was recorded earlier, with session musicians backing McGuinn (on vocals and Rickenbacker) on the latter, Clark on vocals and McGuinn on Rickenbacker on the former. I would have preferred that the whole Byrds play on both songs. Their rougher approach is superior, immediately evident when ‘Whole Lot Better’ kicks in. ‘I Knew I'd Want You’, either way, sounds more like another Byrds-as-Beatles tune than a Gene Clark original. It follows the aforementioned Dylan cover, ‘All I Really Want to Do’. The third and fourth songs on the B side, ‘It's No Use’ (a McGuinn-Clark) and ‘Don't Doubt Yourself, Babe’ (a cover of a Jackie DeShannon song), are an improvement but are hardly essential. The concluding tracks, ‘Chimes of Freedom’ and a cover of the British classic tune, ‘We'll Meet Again’, made famous by Vera Lynn, are even less so.

Johnny Rogan's notes on each track unfortunately do not illuminate when it comes to one of the trickier aspects of listening to the Byrds for novices: who sings lead, that is, whenever the bands breaks away from harmony vocalizing, in other words besides McGuinn's obvious lead vocals on the four Dylan numbers and ‘Bells of Rhymney’, ‘You Won't Have to Cry’, ‘Here Without You’, ‘It's No Use’, and ‘Don't Doubt Yourself’ are dominated by harmonizing, but Clark's vocals seem to come through more, as they do more clearly on ‘I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better’ and ‘I Knew I'd Want You’.

Unlike many of the Legacy C .D. reissues of the Byrds albums, released 1996-1997 and 2000, this release does not feature a hidden bonus track. The bonus tracks are mostly alternate versions, with one out-take, ‘She Has a Way’, being another original from the prolific Gene Clark.

The Byrds, Younger than Yesterday

Originally released 1967, reissued 1996 (Discogs) with six bonus tracks

As with Sweetheart of the Rodeo, David Fricke definitely over-rates Younger than Yesterday in his liner-note essay for its 1996 reissue. Granted, the fourth Byrds album, like Mr. Tambourine Man, begins with an excellent twosome: ‘So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star’, with brass and found-sound (crowds cheering for a Rock band) embellishments suggesting not so much Psychedelia but the kind of experimentation with song forms and recording production that their labelmates Simon and Garfunkel would craft on Bookends; followed by ‘Have You Seen Her Face’, Chris Hillman's debut as a song composer beyond a shared credit on the rejectable ‘Captain Soul’ on Fifth Dimension. This song is about as representative of the classic Byrds sound as you can get and points to Hillman's later successes with the Byrds and a host of other projects.

The rest of side A excels all the way through, the first time in the band's discography that they made the jump (even if it's a hesitant, inelegant jump) from the approach preferred at the time by the major record labels: albums consisting of singles, plus songs not catchy enough to be singles and filler tracks that should have been left in the vault, to albums conceived as collection of songs from which a track or two could work as a single—a huge leap, and one that much of the music trade still considers pointless. Two Crosby tunes, ‘Everbody's Been Burned’ and ‘Renaissance Fair’, represent a big step forward for him and work well enough combined with Chris Hillman's ‘Time Between’ (claimed by Hillman to be the band's first Country-Rock tune) and McGuinn's ‘C.T.A-102’, making for a striking variety of sounds that could be interpreted as a vision of an alternate history of the Byrds, wherein McGuinn, Hillman, and Crosby were able to mesh their growing talents into a Psychedelic whole, especially with McGuinn's futuristic touches on ‘C.T.A.’; and with ‘Renaissance Fair’ (actually based on Crosby visiting the Renaissance Pleasure Faire of Southern California) evoking epochal 1967 events like the Human Be-In and the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival.

That said, Johnny Rogan, again writing notes for each song to accompany Fricke's broader essay, joins Fricke for some laughable, almost cult-like, praise for David Crosby's contributions. Rogan quotes Crosby's high regard for his own song, ‘Mind Gardens’, and both Rogan and Fricke mimic his words like pampering parents eager to encourage any sign of creativity from their (so far) disappointing son. Perhaps if the two critics expanded their listening horizons a tad bit, they would have seen ‘Mind Gardens’ (on the B side) for what it is: a worthy attempt at experimentation with song form, little more, little less. Granted, the song does point to the wondrous peak Crosby would soon achieve as a singer and composer, on his debut solo album, If Only I Could Remember My Name [1971]. Seemingly lacking any semblance of perspective, Rogan says that the non-L. P. single, ‘Lady Friend’, is "groundbreaking," does not explain why; actually it is a fine song that performed its function well: the between-albums stand-alone 45, but I cannot fathom anything "groundbreaking" about it. Another Crosby tune, ‘It Happens Each Day’, not released until the 1980s and included here as a bonus track, he says is "startling". Fricke calls ‘Renaissance Fair’ "two minutes of utter perfection," and ‘Everybody's Been Burned’ "ravishing." Are these guys on whatever drug Jann Wenner gives Rock and Roll Hall of Fame judges that makes them forget how awful they are for honoring the pitiful likes of Green Day while, say, Can and Iron Maiden are ignored?

In contrast, Ric Menck, in Continuum's 33-1/3 series entry on Notorious Byrd Brothers, is merely too generous: about ‘Mind Gardens’, he says, "on first listen, it's all seemingly naive psychedelic imagery over an apparently unstructured melody line, but there is a beautiful, almost ambient feeling to the music." So far, I concur. He adds, "Crosby would continue refining this writing style to perfection in his work with Crosby, Stills & Nash, and more obviously on his first solo album." Here, I must protest, however slightly. First of all, on his three tracks on Notorious, and several of his C. S. N. songs, Crosby did not continue with similar experimentation with song form; and when he did, he married it to to conventional rhythmic backing, notably on ‘Guinnevere’ and ‘Déjà Vu’. When he seemed finally to fulfill the promise of tracks like ‘Mind Gardens’ and ‘Everybody's Been Burned’, on If Only I Could, especially ‘Cowboy Movie’ and ‘Laughing’, he did so by stretching his vocal talents, more so than he ever dared to do with the Byrds, and he was aided by an impressive selection of guests, notably Neil Young as well as several luminaries working at the same time at the still-new Wally Heider Studios on the Grateful Dead's American Beauty and Paul Kantner's Blows against the Empire. That is, he was briefly not the secondary song composer, as he was in relation to, first, Clark then McGuinn in the Byrds and, later, to Stephen Stills and at times Young.

In the end (to be precise, on the B side) the Byrds did not make an album that excels as a whole; indeed, the wider array of styles and voices on Fifth Dimension and Younger make them less cohesive than the band's first and second albums. One cannot help but ask if Columbia Records imposed, or at best strongly insisted upon, the tracking order used on the third-sixths Byrds albums: 6 songs on the first side, 5 on the second, the scantiness of the latter only heightening at times the tossed-off messiness of the tracks included there. Granted, there is less filler on this album than its predecessor, or contemporaneous releases: that is, better than Between the Buttons but not by much. Some backwards-guitar effects on Hillman's ‘Thoughts and Words’, the opening track on side B, elevate it slightly but the track is still only what I call album glue: tracks that hold an album together; they are not star attractions, but they are good enough, you would never skip them because, to do so, one would interrupt the flow of the listening experience. ‘Mind Gardens’ follows; the use of similar effects on the guitars do not help make it seem essential. The sheer uniqueness of Crosby's vocal justifies its presence. Next, McGuinn's version of the Dylan song ‘My Back Pages’, at this point their second-best Dylan cover after ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’, serves as the primary justification for the entire B side. Another Hillman tune, ‘The Girl with No Name’, easily the least distinguishable of his four contributions, and a pointless re-do of ‘Why’, which had already been released as a stand-alone single, end the album with a limp. Repeating the 45 version of ‘Why’ would have been better. Perhaps if ‘Thoughts and Words’ and ‘The Girl with No Name’ had been supplanted, we would have a genuine 1967 Rock classic album. But what else was available? ‘Lady Friend’ is great, if not "groundbreaking," but it was released months later. Another bonus track, the aforementioned Crosby tune ‘It Happens Each Day’, hardly surpasses ‘Thoughts and Words’ or ‘The Girl With No Name’, though it would have worked better in the album's sequence than either of those two. Without Gene Clark, Roger McGuinn either needed to write more originals or craft more excellent adaptations as he had done with ‘I Come and Stand at Every Door’. Indeed, with Hillman's new presence and Crosby at least not making a fool of himself as he had with his version on ‘Hey Joe’ on Fifth Dimension, McGuinn deserves the blame for this album's patchiness. With the band's next album, The Notorious Byrd Brothers, though it was a commercial failure, he would not make that mistake again.

Like many of the Legacy C. D.s of the Byrds albums, a hidden track is to be found after the end of the last bonus track. Here, it is an instrumental version of ‘Mind Gardens’.

–Justin J. Kaw, March 2020

Clarence White Takes the Lead: The Byrds: Byrdmaniax; Farther Along

The Byrds, Byrdmaniax

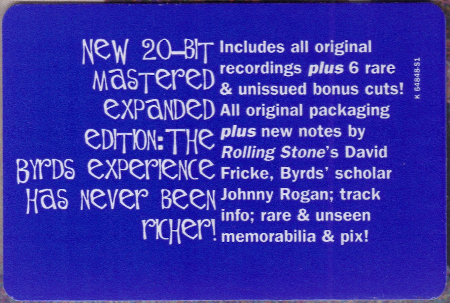

Originally released 1971, reissued 2000 (Discogs) with three bonus tracks

Byrdmaniax, generally considered the Byrds album least worthy of your time, deserves the dismissals that come its way, unlike the similarly-lambasted Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde. ‘Tunnel of Love’ and ‘Citizen Kane’, two Skip Battin-Kim Fowley numbers infused with wry humor, probably would have worked better as part of some sort of concept album conceived by Fowley for his own purposes. Fowley is too much his own animal to serve as a professional songwriter for a famous band. Another novelty, Roger McGuinn's ‘I Want to Grow Up to Be a Politician’, is terrible. Another McGuinn original, ‘Pale Blue’, is decent, it could be album glue, if there were enough of an album here to glue together. It is too similar to the McGuinn-Jacques Levy ‘Kathleen's Song’, left over from their aborted theatrical project and not included (for a reason!) on (Untitled). Both feature orchestral strings that producer Terry Melcher, supposedly without the band's consent, added to the album, to little effect. Oddly enough, two Gospel-infused songs, ‘Glory, Glory’ and ‘I Trust’, ostensibly utterly out of place on any Byrds album, make Melcher's much-maligned additions seem less offensive; that said, they also could have just as well been released as a gimmick 45. The mellow Battin-Fowley piece, ‘Absolute Happiness’, bears Battin's mark more so than the two noted above, comparable to his stand-out performances on (Untitled). Of the three other fine tracks, two, ‘My Destiny’ and ‘Jamaica Say You Will’, are sung by White, and another is an instrumental, ‘Green Apple Quick Step’, where of course he takes the lead. One begins to discern a solo Clarence White album. This would have been a minor treasure, given White's untimely death in 1973, struck down by a drunk driver while loading a van.

The Byrds, Farther Along

Originally released 1971, reissued 2000 (Discogs) with three bonus tracks

Farther Along, recorded quickly soon after the release of Byrdmaniax as the Byrds were eager to make a better album, does not jump around as much stylistically. Two of the better songs were brought to the band by White: ‘Farther Along’, a folk song, and ‘Bugler’, composed by Larry Murray, a guitarist with numerous connections to varied Byrds and their varied projects. White also dominates an excellent Bluegrass instrumental (‘Bristol Steam Convention Blues’). The rest of the album is forgettable: a couple novelty tunes (‘B B Class Road’ and ‘America's Great National Pastime’). The former, composed by Parsons, who otherwise contributed a glue-y track, ‘Get Down Your Line’. The latter, by Skip Battin and Kim Fowley, who contributed another tune, ‘Precious Kate’, about which we could say: attempts... glue-ishness? McGuinn's ‘Tiffany Queen' does not even do that. Battin also sings ‘Lazy Waters’, composed by an obscure session guitarist Bob Rafkin, that fits in well with White's material. Meanwhile, we've got ‘Antique Sandy’, a cobbled-together two-minute mess composed by the entire band with a friend of theirs, Jimmi Seiter—the subject? Seiter's girlfriend. “You can't make this up.” And lest we forget: there's a cover of a Fifties rocker, ‘So Fine’, made famous by the Fiestas. The long and short of it? As with Byrdmaniax, ideally we would have had all involved backing up Clarence White on an album that went full-on Country-Rock; ‘Farther Along', ‘Bugler’, ‘Bristol’, ‘Get Down Your Line’, and ‘Lazy Waters’ from Farther; ‘Pale Blue’, ‘Absolute Happiness’, ‘Green Apple’, ‘My Destiny’, and ‘Jamaica’ from Byrdmaniax. One lead vocal each from McGuinn and Parsons, two from Battin, four from White, plus two instrumental showcases for White. Why not? Sometimes, alternate history is all you have.

Of course I realize the contradiction: Byrds II in its final act should have enhanced its Country element, though I said in my essay on Sweetheart of the Rodeo that the eclipse of Rock by “Americana” Country-Rock in the Twenty-First Century has been unfortunate, perhaps even disastrous. Of course it is not a contradiction at all: simply put, what was good for the Byrds, or at least Roger McGuinn, has not been good for Rock. In contrast to Farther Along, the reunion Byrds album released in 1973 was a mess, seemingly no-one willing to commit their full creative energies to the project, not even the still-obnoxious Crosby, so eager as he was to possess more of a commanding influence on a Byrds album.

The 2000 C. D.s, like most of the earlier reissues, include unlisted “hidden” tracks—on Byrdmaniax, an alternate take of ‘Green Apple Quick Step’; on Farther Along, an alternate take of ‘Bristol’—that begin after the final official track comes to a close.

–Justin J. Kaw, May 2020

Less Would Have Been More: The Byrds: Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde; Ballad of Easy Rider

The Byrds, Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde

Originally released 1969, reissued 1997 (Discogs) with five bonus tracks

The retrospective consensus seems to be that, when comparing these two oft-ignored Byrds albums, Easy Rider is better. Is that merely because it has the song, ‘Ballad of Easy Rider’, made famous by its connection to the film, and thus leading to greater commercial success for the album and its successor, (Untitled)? Or because McGuinn did all the lead vocals on Dr. Byrds, claiming he did not want to confuse listeners, given that the band's new line-up debuted on that album was a big change (or, more likely, he toyed with the idea of becoming the band's only lead singer)? For many long-standing fans, such as Tim Connors, it seems perhaps the negative reception of Dr. Byrds stemmed from its bad production and mastering. If this consensus really exists, at least for once David Fricke goes against the grain. His essay accompanying the 1997 C. D. Dr. Byrds argues that the album possesses a “sturdy, potent quality.” Granted, he frames his remarks by starting out with a typical dismissive remark from McGuinn later his life, suggesting that maintaining the Byrds after 1968 had perhaps been a mistake. The notion, as Fricke suggests, that the later Byrds were too “workmanlike,” ignores the industry-mandated moves that the pre-1968 Byrds went along with, workman-like indeed; he also posits that only in the later years were the Byrds under McGuinn's “stewardship,” ignoring the plain fact that McGuinn had always been at least the nominal leader.

Beyond these split hairs, the big story here: Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde features McGuinn rightly returning to his place as the band's primary song composer—or, rather, song interpreter, as the album begins with ‘This Wheel's on Fire’, the third McGuinn cover of a Bob Dylan song that arguably equals Dylan's own renditions (after ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and ‘You Ain't Goin' Nowhere’). The comparison is unfair, of course, because the first official release of ‘This Wheel's on Fire’ was on the Band's Music From Big Pink, as it was co-written by Dylan and Rick Danko. That version is a classic, bar none. But we have Dylan's version too, on The Basement Tapes, and McGuinn's is better. Two other McGuinn tunes, ‘King Apathy III’ and ‘Bad Night at the Whiskey’ (the latter with lyrics written by a friend of his, Joey Richards), also offer plenty of intrigue.

Much like an outside project pursued by McGuinn would fall apart but ultimately enhance the (Untitled) album (in that case, the unfinished project was a musical created with Jacques Levy), Dr. Byrds is aided by the inclusion of two songs McGuinn developed for the soundtrack to the “psychedelic” film Candy, even as the namesake track, ‘Candy’, was rejected, according to Rogan's song notes in the 1997 reissue because McGuinn composed it with John York, an unknown relative to Dave Grusin, with whom McGuinn composed the other Byrds contribution, ‘Child of the Universe’. The mere fact that McGuinn got this job is peculiar: a self-proclaimed Christian (albeit, at the time a hippie Christian devotee of the ecumenical Subud) soundtracking a farcical journey of soft-porn escapades? The track, ‘Candy’, as it turns out is one of several instances in the later Byrds' oeuvre of McGuinn pushing the limits of his art, adapting well to the post-Psychedelia world. ‘Child of the Universe’ is also no bore, but since it was included on that soundtrack, its placement here is somewhat redundant, like the inclusion of ‘Why’ on Younger than Yesterday. The album ends with a medley: Dylan's ‘My Back Pages’, the instrumental ‘B J Blues’, and the Jimmy Reed tune ‘Baby What You Want Me to Do’, that mildly amuses this listener; it is filler.

The Byrds, Ballad of Easy Rider

Originally released 1969, reissued 1997 (Discogs) with seven bonus tracks

In contrast, Ballad of Easy Rider does not hold up as well after all these decades. ‘Ballad of Easy Rider’, formally a McGuinn original but, as legend has it, with the lyrics co-written with Bob Dylan; McGuinn's cover of Woody Guthrie's ‘Deportee’; and ‘Jesus Is Just Alright’ are the bulk of what the album has on offer. ‘Jesus’ may very well be the only track where the short-lived Byrds II-with-John-York version of the band gelled: Gene Parsons witnessed the song being recorded by the Art Reynolds Singers, he brought it the band, they all sing but McGuinn seems to cut through the most, Clarence White's fuzzy guitar is perfect, the song should have been a hit.

Meanwhile, York, Gene Parsons, and Clarence White all try their hand at lead vocals, with paltry results. The band's take on ‘Oil in My Lamp’, a traditional Christian hymn, features a nice electric-guitar embellishment from White, but he also serves as the lead singer, and his performance is downright odd; like ‘Truck Stop Girl’ on (Untitled) we hear a lot of slurring and mumbling in a sort of faux-Country voice. Thankfully, his vocals improved considerably on the final two Byrds albums. Parsons proves more capable on ‘There Must Be Someone’, composed by Vern Gosdin (who would go on to have a successful career in Country music), and his own ‘Gunga Din’, but neither song catches the ear. The latter is often praised as an exemplary late-Byrds cut, but to me it sounds too much like Glen Campbell's ‘Wichita Lineman’. John York takes his single lead vocal on a Byrds album, and it's a song about a dog, ‘Fido’. There's nothing wrong with it, it has a sort-of drum solo, blah blah. McGuinn's dog song, ‘Old Blue’, on Dr. Byrds, is better, as silly but catchy as it needs to be. Not for the only time on the album, we wish were back on Dr. Byrds. As soon as I say that, though, we must point out that McGuinn offers a stinker vocal performance of his own here: Tim Connors in particular gives a harsh take on McGuinn's fake-Irish accent on the folk song ‘Jack Tarr, the Sailor’. I want to like the song because of the nice production, but he is right about the vocal. And ‘It's All Over Now, Baby Blue’ is one Bob Dylan cover too many. McGuinn's version is inoffensive but, by 1969, there already had been a heap of covers of that song.

What if the band had abandoned their practice of releasing two-albums worth of material annually? What would make the cut on this imagined single 1969 Byrds album? The longer version of ‘Ballad of Easy Rider’ (thankfully included as a bonus track on the C. D., allowing the listener to program it instead of the truncated original); ‘Tulsa County Blue’, but not the Easy Rider version, rather the alternate version with York singing lead, as he did in concert only to have McGuinn take the lead in the studio (also available on the C. D.); ‘Jesus Is Just Alright’; and ‘Deportee’ from Easy Rider; ‘This Wheel's on Fire’; ‘Child of the Universe’; ‘King Apathy III’; ‘Candy’; and ‘Bad Night at the Whiskey’ from Dr. Byrds. Finally, the choice between the two silly songs about dogs can go either way, though ‘Old Blue’, being sung by McGuinn, is a better fit for the Byrds. Ten tracks—good enough! Perhaps ‘Fido’ could be paired with ‘Nashville West’ (from Dr. Byrds) as a side-project 45, since the Byrds doing a cover of an instrumental that another band was named for (even when White and Parsons were in that band and wrote the tune) seems as aimless as many claim this era of the Byrds to be.

–Justin J. Kaw, October 2020

Workaday Byrds

The Byrds, Turn! Turn! Turn!

Originally released 1965, reissued 1996 (Discogs) with seven bonus tracks

Throughout the Byrds' second album, the listener encounters the fundamental problem with Folk-Rock in it strictest form: harmonic compexity that always impresses certain critics (and fellow musicians) fails to rescue the performances from songs and singers that fit in better with the Folk Revival, being awkwardly pinned, like insects in a child's science experiment, to stilted beats. This problem hampered the first album, and would linger in 1966-1967. It hurts Turn! the most. Like its predecessor, the album is roughly split between Gene Clark originals and Roger McGuinn covers (and ‘Turn!’ as a 45 release had another Clark tune, ‘She Don't Care about Time’, on its B side). Critics and fans have justly praised Clark's songs in the half-century since these two albums appeared. His own sad fate (somehow addiction problems felled him, but not Crosby) adds a great deal of poignancy to all of his work. Another reason for the accolades, though, is that Clark's songs lack the rhythmic awkwardness of some of McGuinn's renditions of Dylan and folk songs, especially ‘All I Really Want to Do’ and ‘Chimes of Freedom’ on the first album. Indeed, the notion of McGuinn as a frontman ill-suited for such a role, lacking compositional prowess, applies to two early points in Byrds history: on Fifth Dimension and Younger than Yesterday, after Clark had left and neither Crosby nor Hillman had much to offer; and in 1965, when Gene Clark churned out plenty of songs for the band's picking. Maybe the practice McGuinn got rejecting Clark songs unfairly helped him when he had to reject Crosby songs, fairly.

Either way, two of his performances on Turn! are mediocre: a Dylan piece, ‘The Times They Are A-Changin'’ and the album's final track, ‘Oh! Susannah’. The band's take on another Dylan tune, ‘Lay Down Your Weary Tune’ (an unheard song for many, as it had been cut from Dylan's third album, The Times They Are A-Changin') is more stilted Folk-Rock; arguably harmony vocalizing does not suit the melody well. McGuinn's two original compositions, ‘It Won't Be Wrong’ and ‘Wait and See’ (the latter co-credited to Crosby) are good enough to be album glue. ‘It Won't Be Wrong’, however, sounds too much like the Beatles songs of the time. Perhaps it could have been the B-side track for ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ instead of ‘She Don't Care about Time’. If the latter had been included, another Clark song, ‘Set You Free This Time’, which to my ears is insufferably maudlin, could have been set aside for future archival release. On a positive note, not only is McGuinn's adaptation of ‘Turn!’ brilliant, but his version of ‘He Was a Friend of Mine’ (which featured original lyric contributions on his part) remains a poignant glimpse into the feelings of many Americans toward the murder of John Kennedy. In fact, the performance undoubtedly played a role in the mythologizing, at times ridicously contrary to the historical record, of Kennedy's time in office, a popular activity in the decades since, especially among those of the Baby Boom generation.

The Byrds, Fifth Dimension

Originally released 1966, reissued 1996 (Discogs) with six bonus tracks

Right at the outset, on Fifth Dimension's first (somewhat-titular) track, ‘Fifth Dimension (5D)’, of the band's third album, the future course of the Byrds' history is clear. McGuinn mostly sings on his own, his vocal presence compelling but not commanding: the backing vocals of Crosby and the others providing limited support that nonetheless seems necessary not supplementary. McGuinn's trademark 12-string electric and the overall fine production prove capable of sustaining the song given its so-so melody, plodding rhythm, and awkward lyric. In other words, though McGuinn clearly had the talent and ambition to take the lead in a group that would otherwise descend into messy anarchy, he was not writing enough songs himself, and the support he was getting at this point in the Byrds' career did not suffice. First of all, Gene Clark, who had been the band's primary contributor of original songs, had quit the band, participating only slightly in the recording of this album. Second, Chris Hillman had not yet began writing his own songs. Third, David Crosby, unfortunately, had. Granted, his contributions do not wreck this album and the following Younger than Yesterday; in the end, both albums, for the time when they were released, are essential listening for their time and place, but not the classics that Rock critics dutifully proclaim to be. That is: not hampered by filler tracks but certainly not yet consistently good or forming a cohesive whole in a way that would soon become standard, even perfunctory, in Album-Oriented Rock.

Still, Crosby could have made this album, and especially Yesterday (when Hillman began contributing original compositions) into bonafide Sixties classics if his songs had come anywhere close to the inspired ‘Eight Miles High’, with McGuinn's now-legendary John Coltrane-inspired electric guitar. Or, to put it another way, if they had been as compelling or plentiful as Gene Clark's. Instead, since McGuinn also contributed the lead vocals to two folk tunes, ‘Wild Mountain Thyme' and ‘John Riley’, and Pete Seeger's adaptation of a poem, ‘I Come and Stand at Every Door’; and because he began to refine his own song-composing, he became the leader of the band. A stand-out track, ‘Mr. Spaceman’, the most popular of several quick-tempo, jovial songs dealing with McGuinn's love of aviation and space travel, also unveiled a certain penchant for crafting pop hits like ‘So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star’ on Younger (and potential hits, like ‘Jesus Is Just Alright', and after-the-fact hits, like ‘Chestnut Mare’) and outwardly-similar songs that took on darker hues, as in ‘Artificial Energy’, ‘Get to You’, and ‘King Apathy III’.

Having been understandably needled for covering an excess of Dylan tunes, the band's return to Folkish roots on this album is unsurprising and welcome. ‘Wild Mountain Thyme’ mixes in a moderate amount of Rock, throws a curveball of sorts with its use of Classical strings, and comes out an exemplary deep cut. ‘I Come and Stand at Every Door’, to an even-greater extent, shows how delectable Folk-Rock can be when done right. A poem told from the perspective of seven-year-old Japanese girl who died during the Hiroshima bombing, written by the Turkish poet Nâzim Hikmet, it has been adapted in multiple languages and diverse settings. Its subject matter and McGuinn's stoic performance make the bold choice to turn the poem into a Rock song disarmingly successful.

Meanwhile, McGuinn's guitar almost saves Crosby's ‘What's Happening!?!?’ but Crosby's tune and vocal barely make the track album glue. Having established himself in the Folk scene with his nice voice and pestering networking, Crosby got to take his baby steps with one of the biggest bands in the world. When George Harrison got the opportunity to get his songs on Beatles albums, he had to complete with Lennon and McCartney, who by 1965 were composing separately. And his friends do not try to convince us that ‘I Need You’, for example, from A Hard Day's Night, is an unheralded masterpiece; yet Fricke and Rogan do so regarding numerous Crosby tunes in the Byrds reissues' liner notes. There is no need to deny that the early Harrison tracks are weak when they pale in comparison next to his later works like ‘Something’ and ‘Here Comes the Sun’ (without both of which one cannot imagine Abbey Road as a integral, successul work of art) or ‘Isn't It a Pity’ and other key solo-career songs. Crosby's later achievements, however, were either on the experimental side (If Only I Could Remember My Name) or again as a sideman: he and Graham Nash waiting, hoping for another C. S. N. or C. S. N. Y. album.

In his notes for the 1996 C. D. reissue, Fricke at least admits that filler weakens this album. Except he seems to think that the only toss-off is the final track, ‘2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song)’. In fact, most of side B, beyond its brilliant first track, ‘Eight Miles High', is forgettable. David Crosby, according to Rogan's notes, had wanted to do ‘Hey Joe’ for some time, and the band resisted until other bands like Love and the Leaves recorded it. Turns out they rejected it because Crosby's version is awful; they clearly hoped to avoid embarrassment. An instrumental track, ‘Captain Soul’, does not even hold up compared to other instrumentals that the band did not include on albums. ‘Lear Jet’ is hardly filler, is actually quite refreshing after those two songs and ‘John Riley’, a so-so version of the folk standard, nowhere near as compelling as the classic Byrds takes on traditional songs (‘The Bells of Rhymney’ and ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ on the first and second albums, respectively) and unnecessary on this album after ‘Wild Mountain Thyme’ and ‘I Come and Stand at Every Door’.

A hypothetical alternative could have ‘Eight Miles High’ and ‘Mr. Spaceman’ as 45s backed by ‘What's Happening!?!?’ and ‘Fifth Dimension (5D)’, respectively; and perhaps an E. P. with ‘John Riley’ and ‘I Come and Stand at Every Door’ on one (Folk) side and ‘I See You’ and ‘Why’ on the other (Rock) side (the latter in its original version, as released on a non-L. P. single—that version is a bonus track on this reissue, and Rogan rightly points out that it, and an alternate take also included here, are both better than the version the band would include on Younger than Yesterday). ‘Wild Mountain Thyme’ and ‘Lear Jet’ could have been saved for later. Among the C. D. bonus tracks, a version of ‘I Know My Rider’ (the folk tune that the Grateful Dead would popularize as ‘I Know You Rider’) is fine, no better or worst than ‘John Riley’. ‘Psychodrama City’, another Crosby experiment is at least more intriguing than ‘What's Happening!?!?’ and could have fit in on a better album formed out of this material and the songs recorded for Younger.

Final note: the C. D. reissue's final track, an instrumental version of ‘John Riley’ continues after the song concludes with members of the Byrds talking about the album at the time, apparently from an interview but with the interviewer's questions not present.

The Byrds, (Untitled)

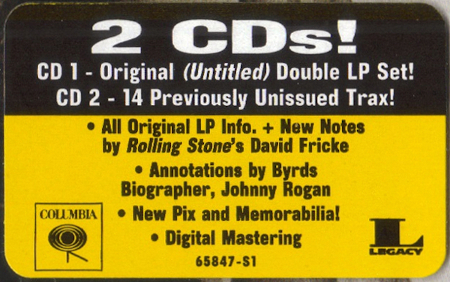

Originally released 1970, reissued 2000 (Discogs) as (Untitled)/(Unissued) with 14 bonus tracks

The double album (Untitled) gets a lot of good marks for being a cohesive, though not exact compelling, album. Many listeners still ignore it to this day. After all, it is not "classic" Byrds. That is, it lacks landmark songs like ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and ‘Eight Miles High’. Fails to offer brilliant examples of Psychedelic experimentation like Younger than Yesterday and The Notorious Byrd Brothers. And certainly did not help launch a hybrid genre, Country-Rock, as Sweetheart of the Rodeo did. Nonetheless, almost every turn (Untitled) takes is the right one. With the replacement of John York on bass by Skip Battin, the Byrds arrived at a line-up that proved to be reliable as a concert attraction and could have turned into a major creative force in the Album-Oriented Rock of the Seventies. Instead, rushed and botched recording jobs doomed the next couple Byrds albums.

The decision to put the live tracks on the first L. P.—according to McGuinn, made by producer Terry Melcher—may at first seem counterintuitive. However, the album begins with a new track, ‘Lover of the Bayou’, a driving rocker allowing McGuinn to sing with more of a haggard voice than usual; he would re-do the song in the studio for his best solo album, Roger McGuinn and Band, a version inferior to this one. The Dylan cover that follows, ‘Positively 4th Street’, was also new to the Byrds. After a few adaptations of the band's early hits that at least have the benefit of being different, if only because the band members themselves were different, the second side of the first L. P. is devoted to an excellent 15-minute, largely-improvised version of ‘Eight Miles High’, with every member (yes, even the bass guitarist) getting a chance to solo. Fans of the early Byrds may hate this performance. Tim Connors, author of the excellent old Byrds web site, Byrd Watcher, for example, does. I disagree; it is exactly the kind of extended concert recording that messy Seventies double Rock albums were made for (see, for example, live albums by Todd Rundgren's Utopia or Blue Öyster Cult).

The studio half of (Untitled) is more a mix of Rock and Country than Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which is arguably more an attempt at Country made by a Folk-Rock band. After all, Clarence White and Gene Parsons had worked as Nashville musicians. Moreover, the album's origins date from a concept for a Country-Rock Western musical collaboration between McGuinn and Jacques Levy, an adaptation of Ibsen's Peer Gynt to be titled Gene Tyrp. This project did not come to fruition, but McGuinn wrote several songs for it that he used on this album and its successor Byrdmaniax.