Heavy Metal Origin Stories

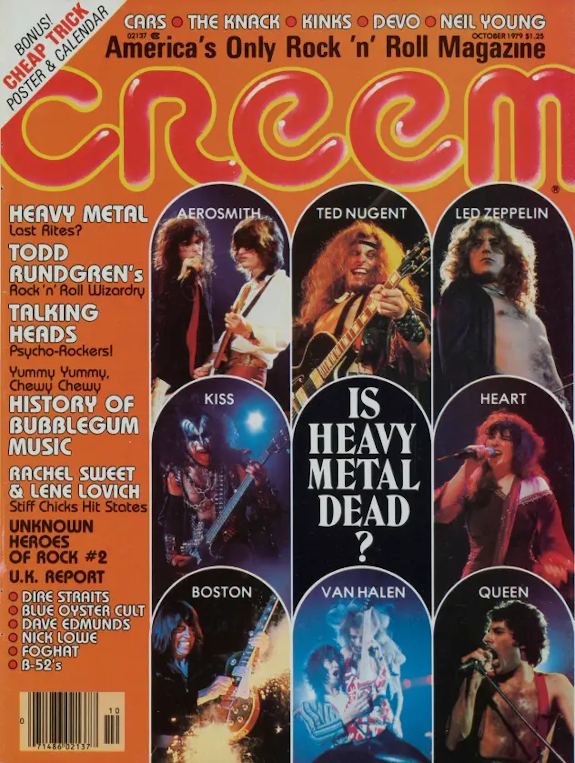

The October, 1979, issue of Creem magazine famously asked on its cover, "Is Heavy Metal Dead?" Only in retrospect does the question seem laugh-out-loud absurd, because the next year, 1980, has been decreed by popular culture's conventional wisdom to be Heavy Metal's peak. Paul Brannigan's article for Metal Hammer, ‘Why 1980 Was the Greatest Year for Heavy Metal’, is a recent (2016) run-through of this argument. The titles of the albums that he mentions can be recited, like a mantra, by most Rock fans: A. C./ D. C.'s Back in Black obviously, being one of the highest-selling albums ever. Also, Black Sabbath's first album with Ronnie James Dio as singer, Heaven and Hell; former Sabbath frontman Ozzy Osbourne's solo debut, Blizzard of Ozz; and career highlights from Judas Priest and Motöhead. But most of all the year stands out because it brought the "New Wave of British Heavy Metal" to international attention: debuts from Iron Maiden, Diamond Head, and Def Leppard, plus Saxon's second and third albums (their best), all noted by Brannigan. He failes to mention first albums from Girlschool and Angel Witch. More debuts, from Raven and Venom, came in '81.

The striking thing about that Creem article, though, is not that its author, Rick Johnson, excluded Motöhead and disliked Judas Priest—two mistakes contributing to his pessimistic take on the genre's health. Rather, it is the bands displayed on the cover: Aerosmith, Ted Nugent, Led Zeppelin, Kiss, Heart, Boston, Van Halen, and Queen. At first, one may think that magazine had to sell copies; perhaps the artists chosen were those who would attract the most wandering eyes at a newsstand. Sure... but that's not exactly what's going on here. Also discussed in the article are Foghat, Status Quo, Wishbone Ash, and Pat Travers. Before this article leads to a double take that could cause neck strain in even the fiercest headbanger, we must remind ourselves that this is 1979, when, yes, Boston and Pat Travers are Heavy Metal—and Mahogany Rush? R. E. O. Speedwagon? They are discussed too. At the same time, Johnson gives his opinion on the current state of many bands, including Kiss, Black Sabbath, and A. C./ D. C., undoubtedly considered then, and now, to be Metal masters, plus others to be expected: Rainbow, U. F. O., Nazareth, Whitesnake. But the point remains: in 1979, one had to stretch the definition of the genre already liberally defined in order to fill up an article assessing the genre. The contrast with later decades is striking: from the early Eighties to the present, there have always been more Metal bands to listen to; yet that multitude somehow hew to certain self-imposed genre strictures, the hidebound among them serving as self-appointed guardians at the gate.

The golden age of Metal launched with that turning-point year of 1980 ultimately changed the definition of Metal as new subgenres developed, each upping the ante on at least one characteristic of the genre, to the point where many Metallers scoff at the idea of Led Zeppelin being of relevance to them. This led to the standard set-up of categories that explains away the older definition of Metal: on one hand, there is Hard Rock, which includes everything from Deep Purple to Poison to Nickelback, and on the other there is Heavy Metal, which is Mercyful Fate, Metallica, Slayer, Sepultura, Pantera, etc. As easy as this distinction is to make, let us be frank about it: it's easy because anyone can put themselves in the shoes of a stereotypical Metal-meat-head and ask themselves: would that person like Wishbone Ash? No? Then Wishbone Ash is Hard Rock. In other words, we have a way of defining a vast sphere of music based on the assumption that its avid listeners are, to be kind, excessively cliquish.

Before you conclude I am being too harsh on the Metal legions, let's make clear that there is the prim-and-proper, level-headed explanation of this Hard Rock-Heavy Metal binary, offensive to none. The veteran critic Jon Pareles provided a brief explication of it back in 1988, in a New York Times profile of Metallica no less, defining Heavy Metal as a subspecies of Hard Rock, "the breed with less syncopation, less blues, more showmanship and more brute force." Putting aside the fact that, in the decades since, Hard Rock would come to seem more like the subspecies of Metal rather than the other way around... insofar as Glam Metal is defined as Metal (if not, we would have to question whether Metal necessarily emphasizes showmanship) Pareles's "taxonomy" works. Plenty other casual listeners, and critics with no ax to grind, simply note that post-1980 Metal eliminated Blues and other Folk-ish styles of guitar playing, that been central to Rock music, especially Metal. And, indeed, "less syncopation," or different, complex forms of it, not the boogie backbeat of Rock and Soul. These developments reached a point where the genre's definition shifted so far down a proverbial ruler measuring what's included and what's not that the originators of the genre were excluded.

Such a seismic change in a genre's definition is downright weird. On one hand, no-one could argue that the terms defining artistic movements have not changed meaning over time. A term is introduced, often as part of a critique and often merely descriptive if not pejorative as well, hardly as a rallying cry to be accepted happily by those to whom the term applies. (This tendency is evident in the visual arts, most famously with the critic Louis Vauxcelles, who indirectly coined the terms Fauvism and Cubism in his writings, at times negative, about the artists in question.) Looking back at journalistic accounts of Heavy Metal in the late Sixties and the Seventies, artists often refuse to apply the term to their own music. Perhaps the "death" of Heavy Metal in the late Seventies was necessary for younger bands to embrace the term and give (re)birth to its new form, with "Hard Rock" being the pretty-boy twin who got the girls and the money in the Eighties, in the form of Glam Metal (again in its perpetual purgatory, always threatened with expulsion from Metal), but like all early bloomers faded fast, allowing Heavy Metal to win out in the end. But having won that victory, why are Metallers still reluctant to embrace early Metal? Do aficionados of Psychedelia try to cordon off the non-Psychedelic Rock from their favorites? Are they not interested in, even happy to note, the way that the recording techniques and literary themes associated with Psychedelia in 1966-1968 seeped into all of Rock, and all popular music? Conversely, do neo-Psychedelia enthusiasts trumpet their version of the genre as superior to its original Sixties form? In other words, have we decided that the Flaming Lips or the Bevis Frond define Psychedelia and that the Byrds or the Beatles must be measured against them? Of course not. Do students of electronic dance music, digging through record creates, dissecting every microgenre, dismiss classic House music? Nope. Or, rather, certainly some do, but plenty others embrace House whenever certain strains of club music become, alternately, too minimal, complex, or boorish.

Though the Hard Rock-Heavy Metal binary, in removing the likes of Heart and Queen from the genre, seems fair and sensible to both Metal fans and those who only casually partake in the genre, in practice, the binary is not so clear. Historians of the genre who accept the Hard Rock-Heavy Metal division cannot agree on its boundaries. We see this when looking at how writers define what should be called, by rights, early Heavy Metal but which often gets called mere Hard Rock. Heavy Metal Origin Denial, let's call it. Some writers are only partially in denial. See, for example, the special-edition magazine 'The Story of Metal 1964-1986', jointly published by Classic Rock and Metal Hammer, which stakes a position slightly different from the Hard Rock-Heavy Metal binary, decidedly giving credit to pioneers like Iron Butterfly, Steppenwolf, Blue Cheer, Sir Lord Baltimore, Bang, Leaf Hound, and Bloodrock, but ignoring simply-Rock artists like some of those found in the Creem article. This perspective is at least better than the snob rejection of Hard Rock. Another example of a writer still calling the early bands Metal (but not the likes of Foghat) is Richard Havers, in his article 'Heavy Metal Thunder: The Origins of Heavy Metal'.

But these are exceptions, created by those especially interested in early Metal. In books marketed more toward fans of later subgenres, Heavy Metal Origin Denial is in full effect. Ian Christe's Sound of the Beast: The Complete Headbanging History of Heavy Metal classifies the early bands as hard rock or protometal, the Seventies being merely the "Prelude to Heaviness," as a chapter title indicates. In the thick of the history, he actually plays it both ways. The first sentence of that chapter states: "Heavy metal came into being just as the previous generation's salvation, rock and roll, was in the midst of horrific disintegration" (referring to Altamont, the Beatles' break-up, Joplin's, Hendrix's, and Morrison's deaths, Kent State, the Manson murders). Within a few pages, though, he writes: "As the epitome of 1970s hard rock bands, Led Zeppelin had an enormous influence on heavy metal." Thusly Led Zeppelin are assigned to the Hard Rock ghetto. And accordingly Black Sabbath are in a category by themselves, not Hard Rock or proto-Metal. The reasons for this are obvious: their literary themes, Ozzy Osbourne's inimitable vocals, Tony Iommi's massively-influential guitar work.

One may expect Eddie Trunk, industry insider and radio/ television host of several popular Metal-centric shows, to appreciate the pop side of the genre. And he does, as seen in his books, Essential Hard Rock and Heavy Metal and Essential Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Volume II. But, as the titles suggest, bands like Extreme, Bon Jovi, and Poison are Hard Rock. Even if he does not place much emphasis on the distinction between the Hard and the Metal (or, to be precise, never exactly defines the two), in using both terms he saves himself from rebukes by Metal fans, who might have quite a tizzy if they picked up a book about "Heavy Metal" and then saw it had a chapter on Lita Ford.

Andrew O'Neill, in his History of Heavy Metal, takes a comedic approach to the subject. In the introduction, he tries to shrug off the problem of defining Heavy Metal with tongue-in-cheek self-deprecation. Not without letting the reader know, though, in a moment of solemnity, that "an overdriven blues band" like Led Zeppelin, in later years "no longer fitted quite so easily" into Metal's confines. He adds, "The early seventies saw the term thrown about with reckless abandon." Why? "Heavy metal didn't exist as a genre in its early days." So what was it? Vast forests of dead trees would like to have a word with O'Neill, wondering how they got turned into the innumerable pages of Rock magazines talking about Heavy Metal music in the Seventies.

Of course, the designation as Heavy Metal of some of the bands mentioned in the Creem article, like Boston and R. E. O. Speewagon, to anyone who came of age from the Eighties onward feels flat-out wrong. But deciding after the fact that they are not, when they were called so by their contemporaries, is also wrong; in fact, it is anachronistic ridiculousness. The term, Heavy Metal, came into use in the Seventies, largely due to the Steppenwolf song, ‘Born to Be Wild’ (though some also give credit to Lester Bangs and other critics using the phrase) and both fans and commentators employed the term as it was understood then quite consistently; that is, no, the term was not used with "reckless abandon." Why should later definitions of the term prevail over earlier? Again, notice what writers like Christe and O'Neill do with that proverbial ruler measuring how much to include. Apparently, the length is set in stone; that is, if the genre gets more extreme, those less extreme are left behind, because the set amount of space has moved to the fringe. As a result, Led Zeppelin is defined by what other artists were doing in 1988 or 1995, when Led Zeppelin did not exist except for an occasional disappointing reunion show. Why not increase the length? I know an obvious answer: those who like the later music greatly out-number those who call "Hard Rock" Heavy Metal... again, those cliquish fans dressed to the nines (tens, elevens) in their Spinal Tap-esque ways.

Are Metal fans eager to exclude Hard Rock actually suggesting that Metal is not Rock? If so, good luck. If not, what's the point anyway? One cannot find a history of Metal that fails to acknowledge the term, "Heavy Metal," was used in the Seventies, and that only retroactively has this early Metal been deemed to Hard Rock, as if it failed to reach a higher status known as Heavy Metal. This expulsion of early Metal could perhaps make sense as a practical measure if, say, the difference between Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin were significantly greater than that between, say, Metallica and Burzum. After all, we all want novices to understand what we mean by the term, "Heavy Metal," and if the inclusion of the artists who (let us not forget) were the first artists defined as such is really so profoundly confusing, then new terminology may be appropriate. But such is not the case—or else we would not have whole subgenres like Stoner that sound more like Zeppelin than Metallica. There is a silliness to this that, for me, is more laughable than the notion that Boston are Metal.

Having cast my lot, I ask, how can those writers who appreciate early Metal, like the contributors to that 'Story of Metal' magazine (among whom are Sleazegrinder and Ken McIntyre), help us to recalibrate what we mean by the term, Heavy Metal? What happens when we emphasize the earlier, hippie version of Metal over its later incarnation? The first groups defined as Heavy Metal were characterized by a heightened appreciation and exploitation of the amplified electric guitar and drummers taking on a louder, prominent place in the Rock ensemble. Rock purists of the Fifties generation hated the way that the resulting electronic distortion and heavy beats overwhelmed the singer and the melody (so they claimed); see for example Ian MacDonald's harsh takes on later "heavy" Beatles songs in his landmark book Revolution in the Head, most of all his sharp rebuke of the entire Metal genre in his review of ‘Helter Skelter’.

Reading through accounts of Metal music in the Seventies, especially those written for a general audience, one finds great emphasis placed on the sheer loudness of the music in a live setting: the amplifiers, the pounded-upon drums. Keeping in mind that the mere presence of a large number of amps does not directly correspond to heavy music (see: the Grateful Dead's "wall of sound" set-up in 1974), still we have to wonder: what about the Shoegazer bands? My Bloody Valentine concerts were famously among the loudest ever. I suppose Shoegaze is what happens when a head-banger doesn't raise his head back up to bang it again.

The word, "heavy," was used in the late Sixties to refer to "deep," philosophical subject matter, a characteristic of not only Metal but plenty other Rock and pop of the time. With the extraordinary influence of Black Sabbath's literary themes, introduced so dramatically on their first album, on a song called ‘Black Sabbath’ no less, the words in Heavy Metal songs started to become a unique, defining feature: Satan, witchcraft and the occult, death and dismemberment, all that. But they only became so gradually. Again, if Glam Metal is Metal (note that Christe's book names Mötley Crüe's Shout at the Devil as one of the genre's best albums), then throughout the Eighties we have Metal with subject matter closer to its Blues-Rock roots or its cousin Glam Rock. Moreover, as Christe notes, sociopolitical topics seeped into Metal in the Eighties, especially with the cross-over influence of Hardcore Punk. As much as Sabbath's themes came to be stereotypically Metal, especially due to moral panics about backward lyrics and Satanism, one finds it hard to designate Seventies early Metal to be "Hard Rock" due to its lyrics.

Early Heavy Metal...

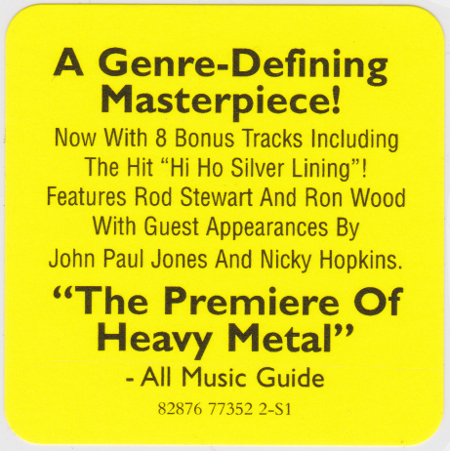

Jeff Beck, Truth

Originally released 1968, reissued 2006 (Discogs) with eight bonus tracks

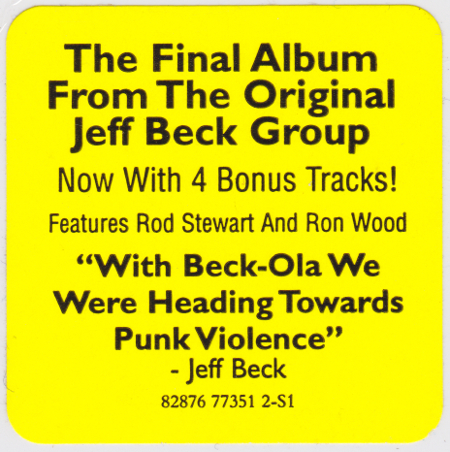

The Jeff Beck Group, Beck-Ola

Originally released 1969, reissued 2006 (Discogs) with four bonus tracks

To be fair, one can imagine later-Metal partisans claiming that Steppenwolf, Jeff Beck, Cream, Iron Butterfly, Spooky Tooth, Humble Pie, and Grand Funk Railroad played Heavy Metal badly. This is better than claiming they were not playing it all. Plenty other listeners may prefer early Metal. These would also likely prefer later-day artists whose music is defined as Psychedelic or Space Rock but which is also quite Heavy, such as the Japanese band Acid Mothers Temple. Or, to a greater extent, the artists often defined as post-Metal, such as Boris and Deafheaven. However, even plenty of Metalheads who listen to Metal, and nothing but, might be surprised by what happens if they extend their arbitrary genre boundaries. Christe, in his "headbanging" history, eagerly shows the influence of Hardcore on Heavy Metal, and the cross-over artists who bridged the Punk and Metal worlds. But a vast realm of Indie Rock, what is generally called post-Hardcore, does not get the attention it arguably deserves in any fair, open-minded history of Metal. Funnily enough, in his dismissal of Indie, Christe throws a clumsy insult Sebadoh's way—and yet that band's leader, Lou Barlow, of course has also been the bass guitarist for Dinosaur Jr. for much of its history. If we used the term, Heavy Metal, the way it was in the Seventies, Dinosaur Jr. by rights would be considered a major Metal band of the past 40 years.

On that note, we cannot but point out that few later-day artists are eager to embrace the term, Hard Rock. Not bands like Acid Mothers Temple or Sleep or the Melvins. Maybe Bon Jovi, when they sought to distance themselves from Glam/ Hair Metal. Anyone else? Hard Rock as a descriptive term is not appealing—no surprise, given that it has largely come to be used in such a pejorative fashion, indicating what certain bands lack in order to have failed to be Metal. Obviously a lot of bands were called Heavy Metal, and like to call themselves Heavy Metal, simply because the term sounds great. Besides, is not Heavy Metal hard? So it is Hard Rock? How about that. In fact, it is later Metal, especially of Speed/ Thrash variety, that sounds "hard," as compared to the heaviness of earlier Metal, especially Black Sabbath, as well as later genres that follow the Sabbath model more closely: Doom/ Black/ Sludge/ Stoner. But, again, I do not want to be anachronistic and try to define Hard Metal as a genre in order to discourage use of the term, Hard Rock. We're trying to create less confusion here, not more.

Where could the term, Hard Rock, still be useful, in its limited way? (Appropriately comparable to Soft Rock, which is used in at least a couple different ways to refer to certain Seventies Rock artists). It could definitely apply to bands that are mostly down-the-line Rock (what the industry began to call Pop/Rock) but who make use of Metal beats and guitar riffs as needed. Some of those mentioned in the Creem article could fit, especially Boston and R. E. O. Speedwagon. It could fit other Progressive acts that moved toward the heavy side of mainstream with a neutered version of their music: Phil Collins' Genesis, Foreigner, Asia. This conceptualization of Hard Rock, as a term remarkably amorphous (again, like Soft Rock) also helps make sense out of Pareles' positioning of Metal as a outgrowth of it. Still, in this sense, the term is useful only as part of a Venn diagram, especially when considering the wide panoply of sounds heard in Seventies Rock: from Henry Cow in one direction to Peter Frampton in another, from Judas Priest to John Denver, from Fela Kuti to the Clash, from Frank Zapppa to... Frank Zappa.

Indeed, Rock in the Seventies was both more diverse in its sounds, yet more uniform and united in the social settings that housed it. Only with the outright hostility, or at best affected indifference, among genre-scenes like Disco (switching to "Dance" after the anti-Disco mania), Punk/ Indie, and post-1980 Metal did the "monoculture" of Seventies Rock dissipate, thus making the space needed for post-1980 Metallers to make the mistake of thinking they had the genre to themselves. Many Rock critics and listeners criticized Metal in the Seventies precisely because it felt like a challenge to them, it being part of their community; whereas in the Eighties the obscure new genres and artists of Metal that weren't Glam (and not on M. T. V.) could be easily ignored by the Rolling Stone/Live Aid mainstream. All the Seventies critics who were skeptical of Metal, or rejected it outright, worried that the Heavy bands represented Rock becoming stupid, devoid of its revolutionary impact. Besides, as far as they were concerned, their harsh stance was par for the course. The gods of Rock were supposed to be brought down to Earth. Look no further than the Rick Johnson Creem article. How does he define Metal? "Like all other dumb labels for music (New Wave, Southern Rock, $7.98) it's nearly impossible to define and none of the groups ever really fits the definition anyway." Also: it's "as memorable as your most unforgettable blackout"; sports "production values that vary between thin and asleep-at-the-wheel"; and, ultimately, concerns "the love/hate relationship between fan and fan's brain." This is self-aware (self-parodying) criticism, reflecting the time when Rock was bigger than ever, but precisely as such also, like K-Pop in the early Twenty-Twenties or Grunge in 1992, worthy of as much scorn as praise.

Heavy Metal?

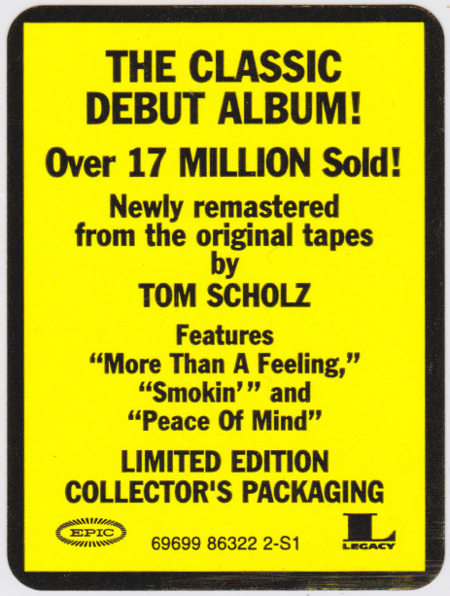

Boston

Originally released 1976, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

Boston, Don't Look Back

Originally released 1978, reissued 2006 (Discogs)

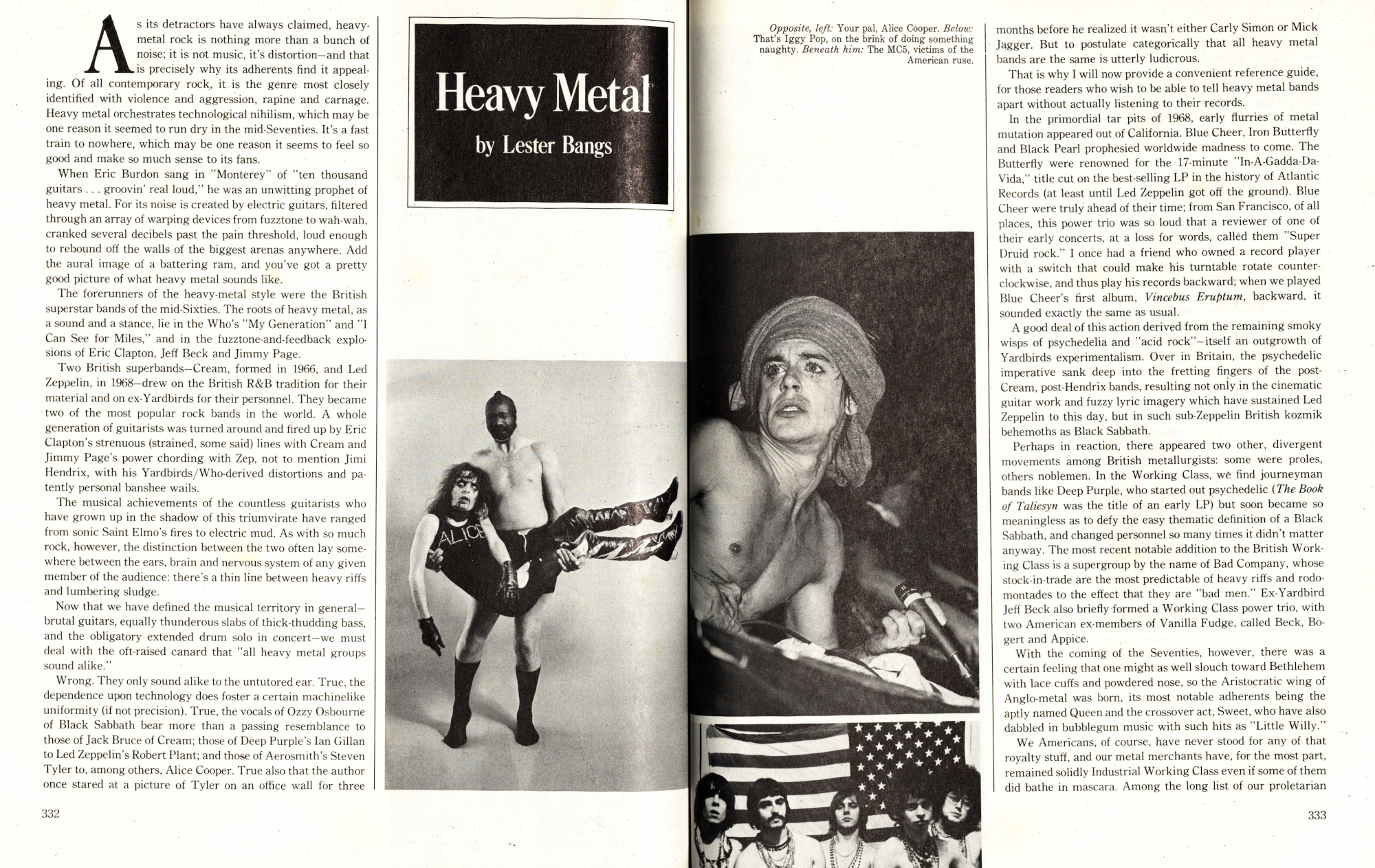

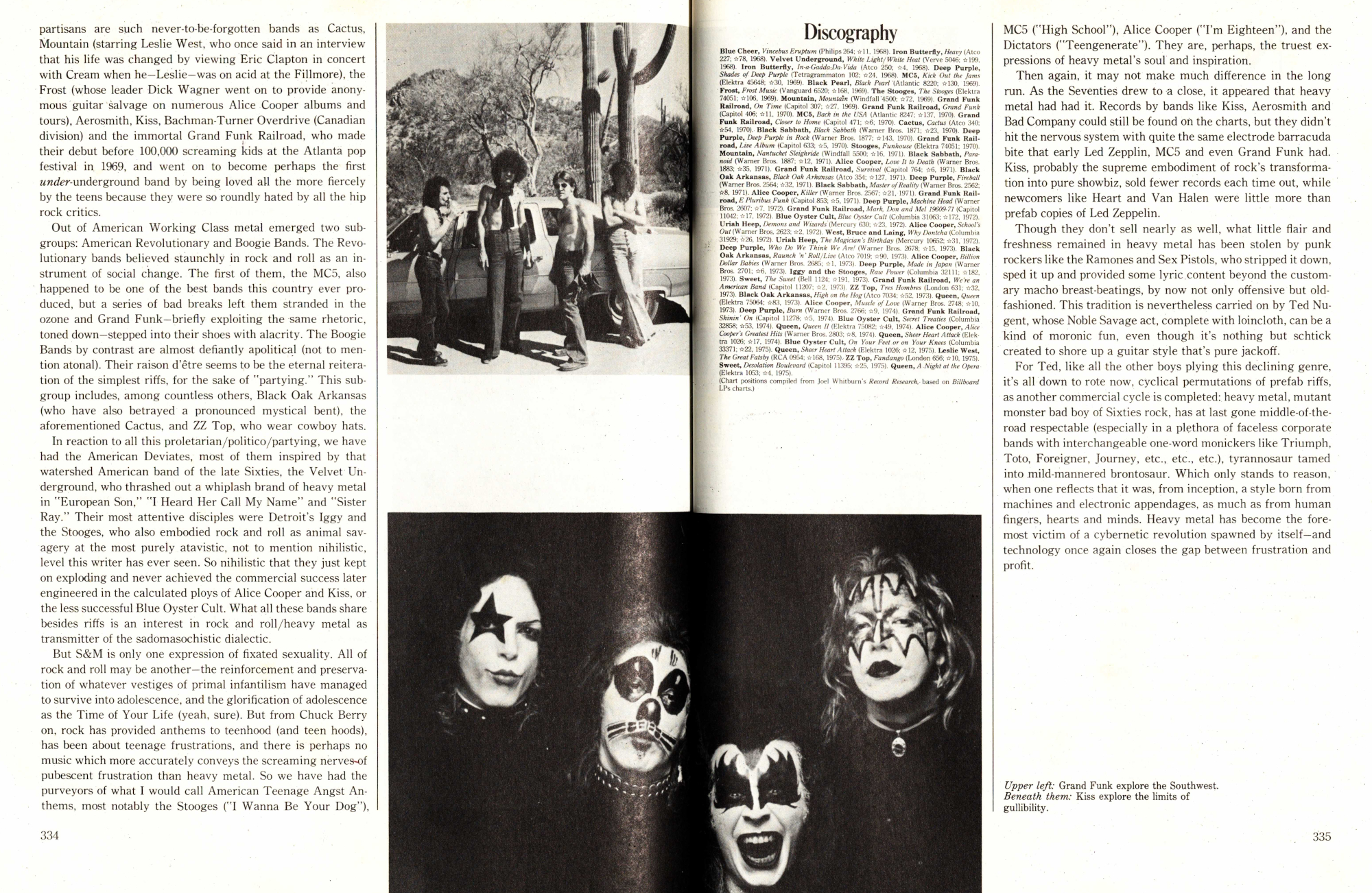

One need not rely on that Creem article in order to immerse oneself in a world wherein Queen or Aerosmith, not Morbid Angel or Sepultura, equate with Heavy Metal. Lester Bangs himself, writing in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll in 1976, shared Johnson's negative take on the genre's health in the late Seventies, and more importantly had no problem considering Heart to be Metal. He also includes Black Oak Arkansas, Z. Z. Top, Uriah Heep, and the Sweet. In fact, he notes that there are more bands who fit into his category of "Working Class" Metal, especially in the U. S., for example Mountain, Aerosmith, and Grand Funk Railroad, than his "Aristocratic" and "American Deviate" branches of the genre. His diagnosis of the genre's ill health comes derives from the following symptoms: the sudden decline of Kiss, the lack of innovation ("Heart and Van Halen were little more than prefab copies of Led Zeppelin"), and the "moronic fun" on offer from Ted Nugent suggesting that the genre has "gone middle-of-the-road respectable," pointing also to Triumph, Toto, Foreigner, and Journey. For Bangs, "Heavy metal orchestrates technological nihilism, which may be one reason it seemed to run dry in the mid-Seventies"; "its noise is created by electric guitars, filtered through an array of warping devices from fuzztone to wah-wah, cranked several decibels past the pain threshold, loud enough to rebound off the walls of the biggest arenas." Again, an emphasis on the loudness of the music, in the moment of hearing it live in concert. Though he defends the genre from its lazy Seventies rejectionists, Bangs, having embraced the Punk critique of popular music, cannot but be skeptical of "a style born from machines and electronic appendages"; because technology (or, more accurately, the commercial marketplace, responding to a product's popularity) "closes the gap between frustration and profit" and makes a mockery of the consumer's pitiful identity. This perspective is harsh, but it helps us understand Metallers' awkward passive-aggression about inferior Hard Rock that fails to satiate their uptight standards.

Another compelling source is The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock, very popular in its day, originally published in 1976 and edited by Nick Logan and Bob Woffinden, writers for the U. K. weekly New Musical Express. The entries there mostly refuse to categorize artists by genre. They are all "Rock," as the title suggests. Given that the British tended to say, "pop," instead of the word, "Rock," this book certainly captures Rock's imperium at its peak. Soul is included; Reggae too, though not other "World" genres. This book says of Blue Öyster Cult: "widely considered foremost extant U.S. exponent of heavy metal rock"; Kiss: "heavy metal grunge"; while Ted Nugent offered "no-frills, heavy-metal chunderings." Iron Butterfly? "Archetypal American heavy metal outfit." Led Zeppelin? "The definitive dizz-buster heavy metal rock combo." Granted, the phrase, "hard rock," comes up at times too. Regarding Queen, the encyclopedia says: "After all, heavy metal had never been fully exploited as a commercial force in the U.K.: what Queen did was to take the hard-rock riffs, overlay them with vocal harmonies and manifestly commercial melodies and filter the whole via superb production." Here, we have "hard" riffs being a defining feature of Metal.

All this confusion only adds to another problem: many standard Rock histories, and a great deal of Rock criticism, as noted above tending to be disrespectful if not hostile toward Metal, still do not give the great early Heavy Metal acts their proper place in Rock history, especially in the Seventies and Eighties, which an excess of older Rock fans perceive as a benighted era. Ten groups—Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, Alice Cooper, Blue Öyster Cult, Kiss, A. C./D. C., Judas Priest, Motörhead, and Van Halen—generally deemed to be the biggest Metal acts of the Seventies, releasing debut albums in the years 1969-1978, are foundational listening for all Rock music. If you put these 10 front and center in the history of Rock (plus Queen and Rush, two groups commonly called Metal at the time, to make it a dozen), you avoid the mistake of the Rolling Stone/ Rock and Roll Hall of Fame traditionalists who want to live through 1956 or 1965 again and again. And you also avoid the mistake of certain lovers of the "art" side of Rock, or experimental music, or Free Jazz (all of which I love), who sadly let their appreciation of such musics turn them into reactionaries who greet the mention of anything "mainstream" with awkward silence, po-faced in their black denim, unless the Wire magazine lets them know the time has come to celebrate an artist previously considered gauche, either ironically or completely ignoring their former stance. The problem with Metallers ghettoizing Hard Rock is that they of course also ghettoize Heavy Metal, allowing others a free pass to conceptualize something like "Rock music in the Seventies and Eighties" while ignoring or belitting artists who rank among the most commercially successful and aesthetically influential.

Heavy Metal.

Van Halen

Originally released 1978, reissued 2015 (Discogs)

Van Halen II

Originally released 1979, reissued 2015 (Discogs)

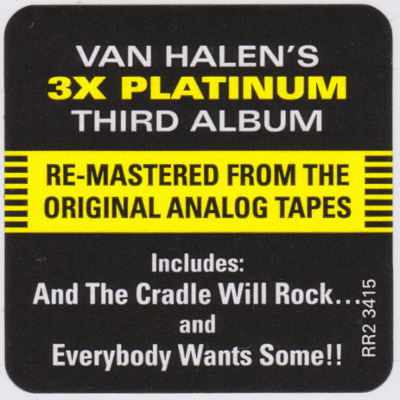

Van Halen, Women and Children First

Originally released 1980, reissued 2015 (Discogs)

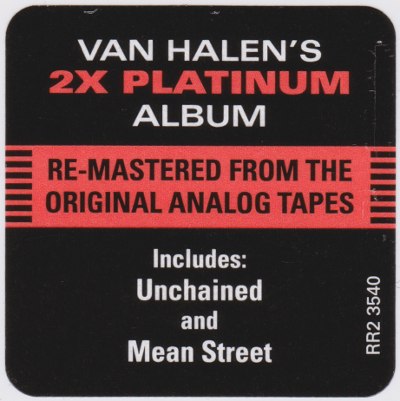

Van Halen, Fair Warning

Originally released 1981, reissued 2015 (Discogs)

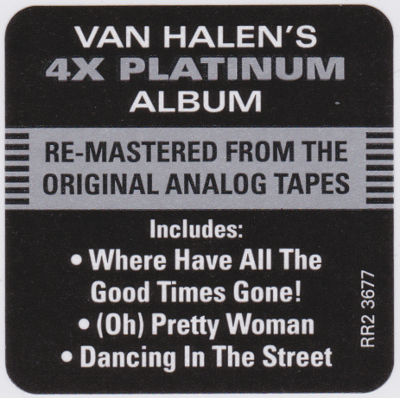

Van Halen, Diver Down

Originally released 1982, reissued 2015 (Discgs)

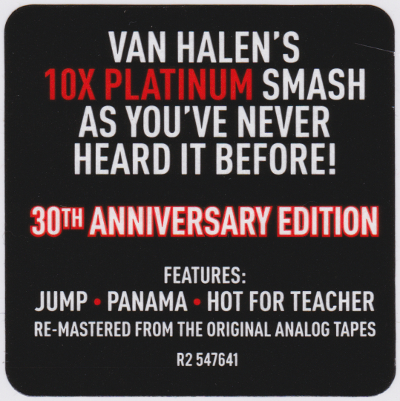

Van Halen, 1984 (MCMLXXXIV)

Originally released 1984, reissued 2015 (Discogs)

Summing up, there were multiple mainstreams in Seventies Rock, and Heavy Metal was one of them. Another was characterized by the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, James Taylor, the Doobie Brothers, Steely Dan. Post-hippie head music, but for sitting most of all—not to say that at many concerts attendees weren't standing. But the music is made for sitting, like you can see watching old episodes of Midnight Special. Heavy Metal was also head music, but for standing, specifically standing and head banging, if only at that point in history slow head banging. Glam Rock was on this side of the divide; not only does Bangs include the Sweet in the aforementioned chapter on Metal, but a revealing 1973 newspaper report from Tom Zito, refers to the Edgar Winter Group. (This Zito piece should be read for its quotes from Blue Öyster Cult manager Murray Krugman if nothing else). A few mainstream artists bridged the divide, most of all the art-school side of Glam Rock (David Bowie, Roxy Music) and Neil Young, both an icon of "singer-songwriter" Soft Rock and master of amplified dissonance with Crazy Horse; or Elton John, chameleonesque like Bowie. But there were more who elided the divide, incapable of being stuffed into this simple bifurcation, a non-mainstream comprised of Progressive Rock, Henry Cow, Frank Zappa, and, later on, Bowie and Brian Eno when they went the Kosmische route, joining the likes of Cluster, Neu!, and Popul Vuh. Prog Rock, despite sharing important traits with Metal and, as noted above, becoming more "Pop/Rock" in the late Seventies-early Eighties, deserves its distinct place, pushing Rock towards its darker, "heavy" side while also directly exploring Jazz and Classical structures and techniques; or, in other cases, e. g. Caravan, keeping alive sounds and methods of the Sixties.

Why not a new, better term for later Heavy Metal? Or maybe "Heavy" is just one of several Metal genres, so that Led Zeppelin and Blue Öyster Cult are Heavy, Death is Death, Mayhem is Black, and so on. Later Metal stakes its claim to be the Heavy Metal because it is louder, faster, more extreme. But even this explanation falls apart. Why, then, wouldn't Hardcore Punk become the Punk? Why is the New York City C. B. G. B. scene still called Punk? Or the Clash and Siouxsie and the Banshees? I suppose there was no easy term like "Hard Rock" to apply to these early Punk artists who did not fit the stereotypical Hardcore Punk mold (except, the absurd solution of post-Punk existing before Punk). Does that not also attest to the relative commercial failure of Hardcore? Or, rather, lack of interest in commercial success on the artists' part. In the end, is that why Metallica is Heavy Metal, and Queen are Hard Rock? The need for clear categories, to assist consumers, radio and television programmers, record-label executives. Because of money, networking, the need for understandable social signals. But new terms for old things tend to whitewash and distort the past. Most of the bands called Hard Rock, those featured in the Creem article, are Heavy Metal—they were then, they are now.

–Justin J. Kaw, February 2024