Albums Lost and Found, Part One: The Who and Frank Zappa

In the years since, roughly, 2011, artists and record labels have brought forth what we could call Rock-and-Roll's holy grails: "lost albums" that listeners, in rarer cases the artists themselves, have wanted available for decades, other than as bootlegs. The Beach Boys' Smile Sessions, 2011; Captain Beefheart's original Bat Chain Puller, 2012; Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes, 2014, and the half of Blood on the Tracks replaced only weeks before the album's release, now available (sort of) on More Blood, More Tracks, 2018.... These are major examples among an overall glut of archival material released to the wider public, at times interfiled with previously-released material in large, multi-format boxed sets. The demands of devoted fans have been met, even in the case of Neil Young, whose progress on his massive Archives seemed stalled for several years only to increase dramatically around 2020; he has let loose a bevy of highly-demanded items, such as the Roxy concert album and two studio albums largely finished at the time of their creation but shelved: Homegrown and Chrome Dreams.

The Beach Boys' Smile will remain Rock's primary "lost album," the one that set the tone for how we talked about such albums, and how we hoped for their eventual release. A rite of passage for avid fans and amateur Rock historians is now irrelevant for most listeners: getting yourself a bootleg of Smile. By the time I was in my twenties, you likely got one of these as a C. D.-R. from a friend who had copied his from someone who actually had a bootleg. For many who owned such bootlegs, the official versions have led to both elation and disappointment. Mystique and intrigue had come to envelope these albums and their inaccessibility to such an extent that the official versions, when they turned out to be similar to what we already heard via informal channels, caused a reaction almost like a crash from a drug high. In this sense, archival box sets of the Twenty-Teens blend in surprisingly well with the entertainment world in which they have been unleashed: "viral" reactions to click-bait promises of something big, quickly dropping out of sight as our blasted attention spans move on to the next reissue.

For those whose attention remains fixed on these archival digs, the delineation of "lost albums," and other rewritings of the past (like that which I created for 'Another Hidden History of Blur'), has become almost a genre of music criticism and historiography in and of itself. The blog, Albums That Never Were, authored by Jesse Miller (or "Soniclovenoize") offers mixes of a seemingly-endless selection of albums that were never released or alternate versions of albums that were. Another blog, The Reconstructor, offers similar downloads. Bruno MacDonald put together the reference book, The Greatest Albums That You'll Never Hear, that covers all of the "lost albums" one would expect as well as album concepts that simply got revised (Kraftwerk's Technopop, for example). These projects give an initial impression that the listener has bountiful treasures waiting. The results will probably only satisfy obsessive fans, but there are exceptions that truly up-end our perceptions of the artist in question. In the past, discographical obscurities could be ignored by the casual listener, no matter how often one band's B-side or another band's bootleg were arguably better than some of their major releases. With some of these archival releases, especially the Beach Boys' and Bob Dylan's, that is no longer the case. The impact of others is not as clear.

By way of example, here we take a look at a few "lost albums"—perhaps the term, compromised albums, would work better—that have been revived, restored, or otherwise reconfigured by way of archival releases and "deluxe" reissues: in part one, the Who's Lifehouse; and Frank Zappa's Funky Nothingness and Zappa in New York; in part two, Neil Young's Homegrown, Chrome Dreams, and Island in the Sun; and Robert Fripp's Exposure. [Part Two to come soon, perhaps later in the year if the fourth volume of Young's Archives appears likely to come out in 2025.]

The Who: A Life House We Already Had

The extent to which "lost albums" were ever completed or can be completed with extant archival recordings of course varies from album to album. The ways in which reissues and archival releases purportedly restoring "lost albums" are described and promoted vary accordingly. Smile was first completed by Brian Wilson on his own, performed live and presented as a new recording in 2004. When the Beach Boys' Smile Sessions came out, a similar arrangement of songs was used. Wilson himself has stated that the 2004 version differed from what he had envisioned in 1967, when the album was supposed to come out. As Smile's devotees have come to realize, once the excitement over Wilson finishing one version of the album died down, the simple fact that it is one version among many, completed after the fact, comes to the fore.

The Who's Life House (or Lifehouse, one word, as it tended to be inscribed before this release), perhaps ranks second to Smile among Rock's "lost albums" when it comes to generating myths and alternate histories. But the 2023 release of the Who's Next/Life House box set, a 10-C. D. (and one Blu-Ray) extravaganza, differs from The Smile Sessions in that it does not reconstruct the album in question. As such, the box is both a capstone of sorts to this "lost album" era of reissues and a hint that, as these myths have come to light, become mere history, listeners understand more clearly that there is no definite right answer to the nagging question of what could have been.

In 1970, the Who had completed successful tours promoting their "Rock opera" Tommy, an album that, like the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, achieved such an extraordinary amount of critical and popular acclaim that it left its creators persistently failing to live up to expectations. And yet both albums have perennially been proclaimed "over-rated" by both critics and listeners hearing them for the first time, wondering what the fuss was about. The Who's Pete Townshend, guitarist, keyboardist, occasional singer, and, in those days, regular willing interview subject of the hyperactive British music press, talked a great deal about a new project, a movie and accompanying music exploring dystopian science-fiction themes, that would surpass Tommy. But after a period of botched attempts to get the project running, Lifehouse was sheepishly put aside. It was replaced by an ordinary album, Who's Next, which however, in terms of its contents, was anything but ordinary, in fact one of the few "classic" Rock albums that unequivocally works as an album, however loosely connected the nine tracks are. A few years down the line, Townshend would successfully create another "Rock opera," Quadrophenia. Like Tommy, it spawned an appreciated (not loved) film, even as its subject matter, unlike Tommy, appealed to British audiences more than American. Anyway, given Quadrophenia's success, the supposed failure to complete Lifehouse stood out all the more.

But what was this concept? Was there an album almost ready to be released? Richie Unterberger's book Won't Get Fooled Again: The Who from Lifehouse to Quadrophenia [2011] covers this period of the Who in great detail, drawing on all the necessary sources, including the aforementioned copious interviews that Townshend was giving. It leaves little doubt that Lifehouse did not advance far in its development, either as a series of performances that took place at the Old Vic Theatre in London, early 1971, or as a movie script (the Who's manager, Kit Lambert, preferring to move ahead with a Tommy film), or as a music album that would in its musical content be shaped by interactions with audience members at said Old Vic performances (such was Townshend's communitarian vision) and in its literary content would match the narrative crafted for a film. Another way of putting it: as much as listeners can reconstruct a double version of Who's Next/ Lifehouse with the generous amount of music recorded by the Who in the period, 1970-1972, the overall concept involved too much for it to be pinned down into a finished product.

Townshend's subsequent attempts to revive the concept, first in the six-disc solo set The Lifehouse Chronicles and now with this new box set, have collectively given listeners a bit much to work through; Lifehouse remains an album that has not been "found." Chronicles includes a radio play, a selection of vintage Townshend-solo demos, and new music. The radio play, though referred to by Townshend in the liner notes as "definitive," not only fleshes out the original concept into a full narrative, with a greater focus on the main character Ray, especially his childhood, but does so accompanied by music that in some cases is not even composed by Townshend. The new box set includes a graphic novel that attempts, after all these years, to make a full narrative out of the original concept. The novel devotes more time to the machinations of the leaders of an authoritarian state that keeps its citizens in lifesuits. These suits, supposedly required for survival due to pollution, feed their inhabitants virtual experiences, as well as sustenance and sleeping gas. In this adaptation, the character of Ray is less important, while the musician Bobby, whose musicianship and spiritual teachings lead to a concert taking place at the titular Lifehouse (this concert has served as the climax of the story in all its different forms) is given greater emphasis.

Regardless, the aural contents of the box set do not attempt any sort of reconstruction of a 1971-vintage Lifehouse narrative. The additional studio material is presented chronologically, followed by live material. First are the demos, some, as noted, already released as part of Chronicles. Not as remarkable as Townshend's demos for Quadrophenia included in the "super deluxe" box version of that album; but those demos are good enough to serve as alternate version of the album. In this case, we hear Townshend beginning to master the home-recording process, playing all of the instruments himself, including large, unwiedly synthesizers. Then there are three discs of session tracks mostly not released at the time, followed by a disc of tracks either released at the time on singles or otherwise in more of a finished state. One of these C. D.s consists of material from a New York session that failed to generate material suitable for an album. The other two discs, from sessions that produced Who's Next and other sessions before and after, offer the significant Lifehouse-related material that could make for a "lost album." There are also four live discs, two from the Old Vic concerts, two more from San Francisco's Civic Auditorium while the band was on tour promoting Who's Next.

The upshot of all this material being available, as well as Townshend's lack of progress in 1971, is that the Lifehouse concept is malleable, the present-day listener can make of it whatever he wants. For example... as noted, all variants of the story have included a climatic concert performed by the Who, or rather a fictionalized version of them. My own dismissive take on the cohesiveness of the Lifehouse narrative led to an easy realization/ rationalization while I was digging through the box. Could we could not, simply enough, imagine that the big final concert is what we hear on the album Who's Next? In this scenario, what we have been listening to since 1971 is a finished portion of the Lifehouse project. The main objection to this notion would be that John Entwistle's song ‘My Wife’ was not written with Lifehouse in mind and accordingly does not fit in with the narrative. But I say no. Make the song fit. We already have a song on Who's Next, ‘Going Mobile’, mostly sung by Townshend, in addition to minor lead parts and harmony vocals by Townshend on other songs, supplementing Roger Daltry's voice as the primary singer and narrator. ‘Going Mobile’ focuses on the narrator's life on the road with his wife. Could ‘My Wife’ be a sideshow, a glimpse of their time on the road? Or, more likely, the narrator concocting a fantasy of life in a different time, more care-free, when a man and wife could indulge in the ruckus behavior described in the song.

The bonus materials in the Life House/Who's Next box set make clear that a double album could have come out at the time, or slightly later, that would have been fine, though obviously it would have lacked the impact of Who's Next. Nor would it have left listeners with a clearer understanding of the Lifehouse story. Again, in my view, there is nothing wrong with that. I say, keep Who's Next as it is (as indeed has been done with the box) and then lay out what a second album could have looked like. The best approach would have been a companion album released in late 1972, so that the two non-L. P. singles of that year, ‘Join Together’ (released in June '72) and ‘Relay’ (November), both of which thematically fit in well enough with Life House themes, could have been included. If Who's Next represented a single event in the Life House narrative, that is, the concert, albeit a concert featuring songs that told stories about more than just that immediate event, then the additional songs would offer more scenes in the characters' lives or more vaguely explore Lifehouse's themes.

The songs that could comprise this second album are: ‘Water’; ‘I Don't Know Myself’; ‘Naked Eye’; ‘Postcard’; ‘Now I'm a Farmer’; ‘Let's See Action’; ‘When I Was a Boy’; ‘Join Together’; ‘Relay’; ‘Pure and Easy’ ‘Time Is Passing’; and ‘Put the Money Down’. (Other songs that did not get past the demo stage but which are tied to Lifehouse, notably ‘Mary’, are for now being put aside.) Three of these, ‘Let's See Action’, ‘Pure and Easy’, ‘Time Is Passing’, were released on Pete Townshend's debut solo album, Who Came First, in 1972. The Who performances, compared to Townshend's, are compelling enough to be included in this hypothetical album. If ‘Pure and Easy’ were to be included, the use of lyrics from the song at the conclusion of the final Who's Next track, ‘The Song Is Over’ ("A note, pure and easy"...), suggests that the latter is reprising ‘Pure and Easy’; and that scenario would arguably require that ‘Pure and Easy’ come earlier in the sequence of tracks. Again, though, this hypothetical 1972 companion album would be presented as material that could, within the Life House story, come both before and after the narratives heard on Who's Next.

Who/ Townshend aficionados should quibble at this point about the inclusion of songs written before Townshend began work on the Lifehouse project. Indeed, five of these potential songs were slated for a 1970 E. P. intended as a stopgap release: ‘Water’, ‘I Don't Know Myself’, ‘Naked Eye’, ‘Postcard’, and ‘Now I'm a Farmer’. And while ‘Join Together’, ‘Relay’, ‘Long Live Rock’, and ‘Put the Money Down’ are at times ascribed to the Life House project, they were recorded after Who's Next was released. The extent to which Townshend had decidedly abandoned any pretense of continued work on Lifehouse is unclear; either way, all four of those songs became part of another proposed concept album, Rock Is Dead—Long Live Rock, which morphed into Quadrophenia. In both cases, however, the inchoate nature of the Lifehouse concept allows for the inclusion of these songs.

Several of these tracks were remixed or even revised by Entwistle for inclusion on Odds & Sods [1974]. The box set makes available the track as they were recorded in the years 1970-1972, and in some cases additional alternate or unabridged versions. The preferable versions, and their placement in the box set, are as follows.

- ‘Water’, abridged version, released as the B-side of ‘5.15’; available on a reissue of that 45 included with the Director's Cut box set of Quadrophenia and included on 1998 reissue of Odds and Sods; unabridged version is 6-4; an alternate take, 6-10, is significantly better and, while I would prefer to use released versions of tracks, this case clearly requires an exception, especially given the unfortunate decision not to include that abridged version in this box set;

- ‘I Don't Know Myself’, as released as the B-side of ‘Won't Get Fooled Again’: 6-5; later, alternate versions, 5-2 and 6-11—either arguably as good as the official version;

- ‘Naked Eye’, edited for inclusion on Odds and Sods, original recording: 6-6; alternate, 5-5;

- ‘Postcard’, remixed and revised for inclusion on Odds and Sods, original recording: 6-7;

- ‘Now I'm a Farmer’, remixed for inclusion on Odds and Sods, original recording: 6-8;

- ‘Let's See Action’, as released as a single, October 1971: 6-12;

- ‘When I Was a Boy’, as released as the B-side of ‘Let's See Action’: 6-13; alternate, 5-12;

- ‘Join Together’, as released as a single: 6-14; alternate, 6-16;

- ‘Relay’, as released as a single: 6-15;

- ‘Long Live Rock’, remixed for inclusion on Odds and Sods, original recording: 6-17;

- ‘Pure and Easy’; remixed for inclusion on Odds and Sods, original recording: 5-1;

- ‘Time Is Passing’, previously-unreleased original, 5-3; mono fold-down included on 1998 reissue of Odds and Sods;

- ‘Put the Money Down’, revised for inclusion on Odds and Sods, original recording: 5-15.

Taking into consideration the lengths of several of these tracks, a nine-track album would work best, especially with Who's Next having nine tracks. John Entwistle's ‘Postcard’ is for me the most obvious to exclude, followed by ‘I Don't Know Myself’, which despite its prominent place as a released B-side track is too similar to ‘Bargain’. ‘Now I'm a Farmer’, though directly connected to the Lifehouse narrative, like ‘Postcard’ strays too far into comedic territory. ‘When I Was a Boy’, another Entwistle tune, is also for me of "B-side" quality. ‘Long Live Rock’ would later be heard in the 1979 documentary The Kids Are Alright and in turn released as a single that year. ‘Put the Money Down’ is a fine track but does not seem to fit in with Lifehouse's themes; one version of the ‘Long Live Rock’ 45 had it as the B-side. Though ‘Long Live Rock’ could fit in with Lifehouse (though perhaps better on Who's Next, to continue with my idea of that album being the concert in the story), in order to keep this imagined "lost album" at nine tracks, I prefer to say these two tracks should have been a non-L. P. single linking Lifehouse to Quadrophenia.

With ‘Join Together’, ‘Relay’, and ‘Let's See Action’ released as singles at the time this 1972 album could have billed as a combination of a singles compilation and rarities collection. But, in that line of thought, why not include ‘The Seeker’, (track 6-1) the band's non-L. P. single from 1970? That would also make that single's B-side, ‘Here for More’ (track 6-2) a contender; not to mention the B-side of ‘Summertime Blues’ (the single from Live at Leeds), Entwistle's ‘Heaven and Hell’, presented in the Life House box (track 6-3) in stereo for the first time, the original recording having been done hastily and released without the band's input. I would include ‘Heaven and Hell’, giving this imagined album a single Entwistle tune, as Who's Next does; ‘Here for More’ is put aside, definitely of B-grade quality. This leaves us to sequence the following nine tracks: ‘The Seeker’, the new stereo ‘Heaven and Hell’, ‘Let's See Action’, ‘Join Together’, ‘Relay’, the alternate ‘Water’, ‘Naked Eye’, ‘Pure and Easy’, and ‘Time Is Passing’. Some of these Who performances do not seem to have been worked out fully, at times feeling uncertain and unfinished, for example the concluding section of ‘Time Is Passing’. But such is a problem with many reconstructed "lost albums."

The tracking that I prefer for this 1972 extra album:

A:

‘The Seeker’ (6-1)

‘Let's See Action’ (6-12)

‘Heaven and Hell’ (6-3)

‘Join Together’ (6-14)

‘Water’ (6-10)

B:

‘Pure and Easy’ (5-1)

‘Time Is Passing’ (5-3)

‘Relay’ (6-15)

‘Naked Eye’ (6-6)

Finally, if one prefers a reconstruction of a Lifehouse that would both subsume and replace Who's Next, turn to the aforementioned Albums That Never Were site and its double-album version put together before the release of the new box set.

Frank Zappa: Funky Nothingness, or: Chunga's Revenge's Revenge

Given that Frank Zappa, like Neil Young, was a determined, obsessive archivist of his own music, the Zappa estate, as led until recently by his widow Gail Zappa but most of all by sound engineer Joe Travers, unsurprisingly presented numerous early examples of the archival trend in the reissue business. Among aged or deceased Rock legends, only the Grateful Dead and King Crimson rival Zappa when it comes to multi-disc reissues, the only aspect of the C. D. portion of the business that expanded in the Twenty-Teens. Documentation of Zappa's storied Halloween concerts in New York began in earnest in 2003 with a curio D. V. D.-Audio release, Halloween, documenting the 1978 holiday concert, to be followed by box sets devoted to the 1973, 1977, and 1981 Halloweens. The original stereo mix of Freak Out! along with a trove of materials from that album's sessions arrived in 2006 via the 4-C. D. Mofo, which thankfully turned out to be the first of numerous reissues of Zappa's albums in their original L. P. mixes instead of Zappa's Eighties remixes. The orchestra-only, early version of Lumpy Gravy came via a larger set called Lumpy Money in 2008. In this decade, we got the 1974 Roxy concerts in their entirety, the Hot Rats Sessions, both the original vinyl mix and an alternate tracking of Uncle Meat, an excellent reissue of Orchestral Favorites (finally sporting decent cover art), and a generously-expanded version of the 200 Motels soundtrack album, sounding better than it ever has.

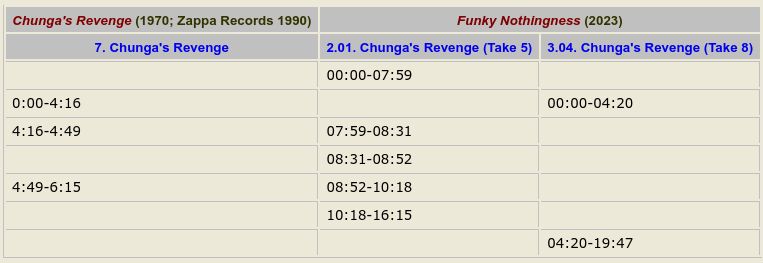

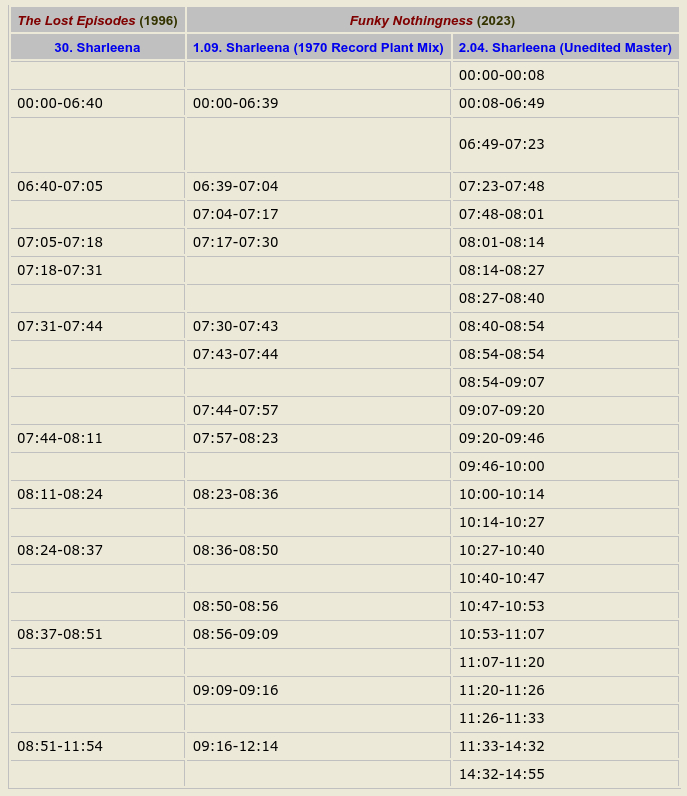

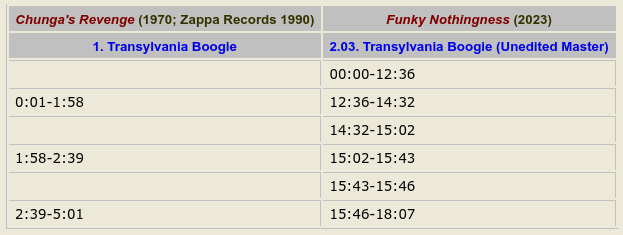

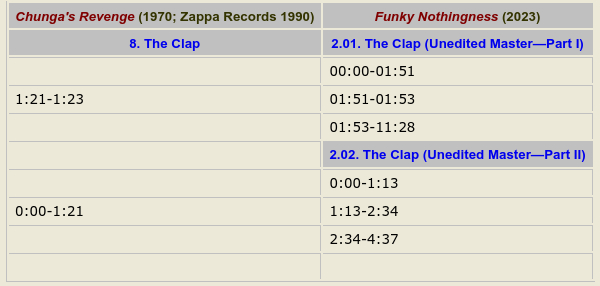

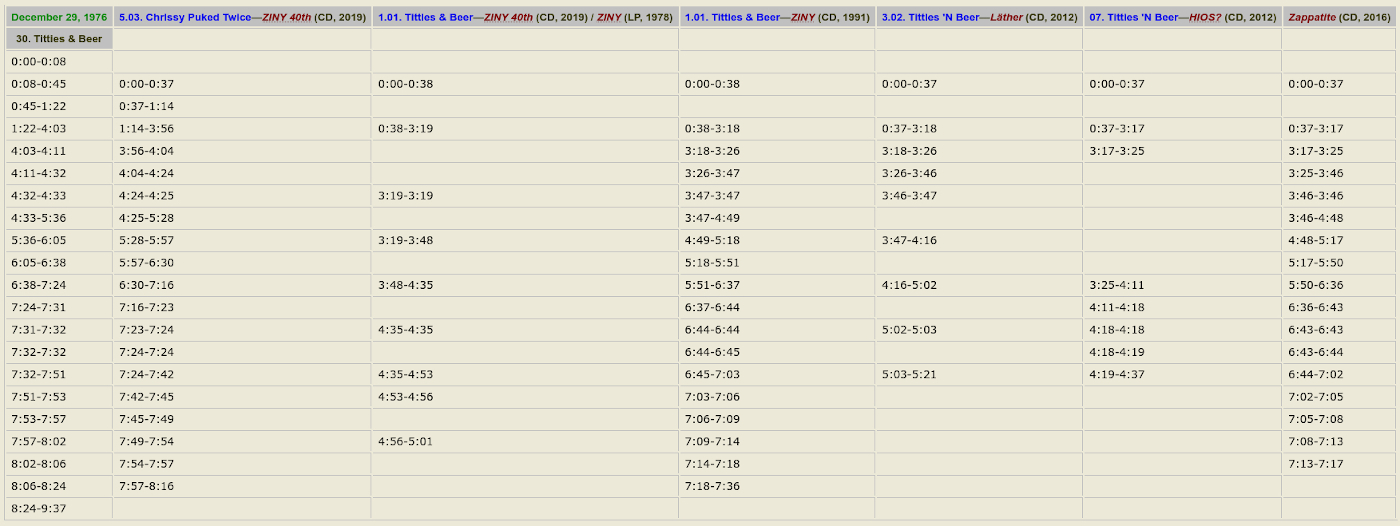

For all of these Zappa archival releases, the listener has an extraordinary resource at his disposal: the website Information Is Not Knowledge, which, among other treats, features charts for many of Zappa's compositions that show the varied edits that comprise final tracks, comparing the differing versions of each recording so that one can see which portions of an unedited master were included in each or, alternately, which of several performances were taped together—and how—to make a released version. These charts help the user to see, for example, how the track ‘Chunga's Revenge’, from the album of the same name, is comprised of portions of two performances. These takes are included in their entirety on the three-disc set Funky Nothingness. We can immediately see why Funky Nothingness was marketed by the Zappa team as a "lost album," as we can begin to create two alternate albums, perhaps with Take 5 on one, Take 8 on the other.

from Information Is Not Knowledge

Such a limited approach may not be necessary given the quality of some of this Funky material. Among the other tracks on this set that could retroactively make "lost albums": a different version of ‘Sharleena’, recorded in L. A., unlike the London-recorded version on the Chunga's Revenge album. This ‘Sharleena’ was on The Lost Episodes, a 1996 archival compilation. Now we have an alternate edit, slightly different and longer, and entitled ‘Sharleena (1970 Record Plant Mix)’, as well as the ‘Unedited Master’. The latter is fine, but if an authentic Zappa edit is available, use it. (Note too that this version of ‘Sharleena’ was set to be included on a different version of Chunga's Revenge, documented of course at Information Is Not Knowledge). Also available now are the unedited masters of ‘Transylvania Boogie’ and ‘The Clap’. The latter is a solo performance by Zappa on a variety of percussion instruments; it is both compelling but also at times a wearing listen. On one hand, Zappa's trimming down the original performance, more than 20 minutes, to one minute and 20 seconds, as heard on Chunga's, left us with little indication of the overall scale of the piece; on the other hand, I would prefer a vintage Zappa edit around 10 minutes long.

from Information Is Not Knowledge

from Information Is Not Knowledge

from Information Is Not Knowledge

Funky Nothingness also features complete studio performances of three notable previously-unreleased Zappa pieces: ‘Funky Nothingness’, a short piece that was originally slated to begin the Chunga album. Despite being given pride of place on this release, as the opening and concluding tune (the latter being an alternate, ‘Fast Funky Nothingness’), this piece barely amounts to more than a silly throw-away that at best could have served as harmless filler on an album of shorter tracks. ‘Twinkle Tits’ is another matter: an extended work-out with the core group heard throughout this set (Don “Sugarcane” Harris on violin, Ian Underwood on keyboards and saxophone, Max Bennett on bass, and Aynsley Dunbar on drums), the liner notes claim that Zappa applied his meticulous recording and editing standards to this piece across nine takes (a false start and a complete take being heard in this set as well) and seemingly intended to release it but never found the time and space to do so. Finally, ‘Moldred’ is formed out of a twenty-minute-plus duo performance by Zappa and Dunbar, called ‘Tommy/Vincent Duo’, with some bass overdubs by Zappa. There are also two edits of this duo without the added bass. The second of these, about six minutes in length, in my listening has proved to be the best.

The other pieces previously unheard on official releases include three cover tunes: ‘Love Will Make Your Mind Go Wild’, ‘I'm a Rollin' Stone’, and ‘Work with Me Annie/Annie Had a Baby’. Two other Zappa originals: ‘Khaki Sack’, an unfinished piece, and ‘Halos and Arrows’, a "guitar experiment" according to the liner notes that is bare-bones ("most of it was recorded over, this is all that was left"), are clearly of "archival" quality only.

Given the length of several of these tracks, we actually have more than two albums' worth of good material with which to make a reconstructed "lost" double album. Four tracks in the set are essential: the complete Take 5 of ‘Chunga's Revenge’ (from which most of the 1970 original came), the complete ‘Transylvania Boogie’, ‘Twinkle Tits’, and Zappa's 1970-vintage mix of ‘Sharleena’. After that, I give myself two options for sequencing this alternate Chunga. One: put aside ‘The Clap’, and have ‘I'm a Rollin' Stone’ accompanied by ‘Tommy/Vincent Duo II’. Of the covers, ‘Rollin' Stone’ is both longer and vastly superior, featuring an excellent Zappa solo. Or: keep ‘The Clap’. I prefer the first option. Adding to the appeal of ‘Rollin' Stone’: Zappa, masterful cut-and-paste magnetic-tape manipulator as he was, used the violin and drum parts from the track for ‘Stink-Foot’ on the album Apostrophe (').

As with plenty of other "lost albums," not least Smile and Chrome Dreams, this one mixes the previously unreleased with the previously released. A version of it with only previously-unreleased material would perhaps only entice the freakiest of Zappa freaks. Besides, the unedited originals of ‘Transylvania Boogie’ and both ‘Chunga’ takes offer a wealth of "new" material alongside the "old" portions heard on the original Chunga's album. My double-L. P. version of Funky Nothingness runs so:

A:

‘Sharleena (1970 Record Plant Mix)’

‘Twinkle Tits’

B:

‘Chunga's Revenge (Take 5)’

C:

‘I'm a Rollin' Stone’

‘Tommy/Vincent Duo II’

or C:

‘The Clap (Unedited Master-Part I)’

‘The Clap (Unedited Master-Part II)’

D:

‘Transylvania Boogie (Unedited Master)’

As an alternate-universe Chunga's Revenge, this sequence makes for an album that is more like a proper sequel to Hot Rats, mostly in that the longer, unedited jams give it more of a "Jazz-Rock" flavor. And, like Hot Rats, this album opens with a vocal track; and, in the version with ‘I'm a Rollin' Stone’, so does the second record.

Other Zappa studio-archival releases have either only offered a few revelations; such as Crux of the Biscuit, already reviewed here at Rockissue (much of the material from that album now having been repeated on the super-deluxe version of Apostrophe (')); and the super-deluxe version of Over-nite Sensation. Or they have offered an almost-absurd excess, namely the aforementioned Hot Rats Sessions and 50th Anniversary Edition of 200 Motels. The Waka/Wazoo box is in the middle of this spectrum. On one hand, there is a complete concert by the larger ensemble that Zappa took on tour in late 1972 to promote the twin albums, Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo, documented by this box (more from that tour, by the way, can be heard on the confusingly-named Wazoo two-disc set released in 2007). The box also includes George Duke-solo demos but most of all a generous amount of material showing the two albums in question being constructed in the studio: alternate takes and mixes and so forth. The "new" material largely comes in the form of "mix out-takes," that ambiguous term for recordings that include material, both alternate or merely alternately-mixed, cut out of the final album mixes. The Hot Rats Sessions, in contrast, is closer to Funky Nothingness in offering unabridged or alternate performances of songs heard on Hot Rats as well as Burnt Weeny Sandwich and Weasels Ripped My Flesh. More "lost albums" could be made out of this material: alternate rats, weasels, weenies, and such.

Greater New York, Lesser Läther

The exemplary Zappa archival release, both in terms of the amount of new material made available and its potential for reshaping our understanding of a particular phase of Zappa's work, is the expanded box-set version of Zappa in New York. The original concert album, derived from four concerts, December 26th-29th, 1976, at the Palladium, was never lost, at least not entirely. It did come out, but belatedly (1978 instead of '77) and in edited form due to the record label's concerns about references to Punky Meadows of the band Angel in the songs ‘Punky's Whips’ and ‘Titties & Beer’. The former was removed entirely; the latter, though having a different subject entirely, was edited slightly because of a brief reference to the contents of ‘Punky's Whips’. Warner Bros. Records made these cuts without Zappa's permission amid protracted disputes and legal finagling among Warner, Zappa, and Zappa's manager Herb Cohen. For the 1991 Rykodisc C. D. version of the album, Zappa restored both of those songs but also added other material, including entire tracks, and remixed the entire album. Finally, with the 40th-anniversary box set, listeners get the material closer in form to its original form, albeit in a way that is at times jumbled and unclear.

Zappa in New York is definitely not one of Rock's mythologized lost albums; it has rarely been ranked as one of Zappa's best. Now, though, with such an abundance of material in the box set, listeners can not only restore the cut portions of the original album, but also make their own versions, likely an expanded version, out of these recordings. Either an imagined "lost album" or the original double can serve as the culmination of what is arguably Zappa's peak as a composer, recording artist, and bandleader: the years beginning with the aforementioned large-ensemble pieces heard on Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo and extending into early '77, when two developments in Zappa's work: toward heavier, yet complex, beats (contrasting with the looser, Jazz-inspired rhythms that had predominated) and biting, crude satire in his lyrics, both contributed toward a decline in quality in Zappa's song-oriented work.

Zappa's line-ups in the years, 1973-1975, usually included drummer Ralph Humphrey, percussionist Ruth Underwood, bass guitarist Tom Fowler, keyboardist George Duke, trombonist Bruce Fowler, and singer and saxophonist Napoleon Murphy Brock (replacing Ian Underwood early on in this period), with a second drummer, Chester Thompson, then a second guitarist Jeff Simmons, being added later (and in turn, Simmons then Humphrey leaving earlier). This group hit the road in February 1973 and formed the core of whatever ensemble you hear at any given moment of the albums Apostrophe ('), Over-nite Sensation, and One Size Fits All. Jean-Luc Ponty was there playing violin at first, plus Sal Marquez on trumpet for a time, but for the most part the core septet of Zappa, Brock, B. Fowler, Duke, T. Fowler, R. Underwood, and Humphrey played together until the spring of '75. After that came a period of persistent membership changes, but Terry Bozio on drums and Patrick O'Hearn on drums definitely made their mark on Zappa's sound. They form the rhythmn section heard on the New York recordings; also heard are Eddie Jobson (replacing short-term member André Lewis, who had replaced George Duke) on keyboards as well as violin, and Ray White, replacing Brock, plus the welcome temporary return of Ruth Underwood. O'Hear and Bozio would stick around for the next phase of Zappa's work, notably with Adrian Belew briefly becoming a sort of right-hand man to Zappa and two keyboardists replacing Jobson (this phase being documented well on the Hammersmith Odeon three-disc set).

One distinguishing trait of the Palladium recordings is the prominent role of Bozio, whose drums are a focal point throughout and who also took star turns on vocals (more like theatrical performances) as the Devil on ‘Titties & Beer’ and a fictionalized version of himself on ‘Punky's Whips’. With the latter track, in which Bozio becomes infatuated with Punky Meadows' pouting succulent lips, being cut out of the album, for many years only those who attended the concerts or heard bootlegs fully appreciated Bozio's central role. The other major distinguishing trait of these concerts was Zappa's one-off collaboration with a New York-based horn section consisting of Michael and Randy Brecker plus players from the Saturday Night Live band (Zappa having played on the show that same month). Also memorable of course is the famed radio and television announcer Don Pardo, who among numerous other broadcasting feats worked at S. N. L. for 38 years, making guest appearances at the concerts, notably on ‘Punky's Whips’ and ‘The Illinois Enema Bandit’.

The performance of ‘Titties & Beer’ from December 29th, the source of the album version, is included on the fifth disc of the box set. It is retitled ‘Chrissy Puked Twice’, as is the performance from December 27th; the alternate title comes from a portion of the song cut from the album version but found in both of these unedited performances. Again, referring to the tables from Information Is Not Knowledge, we can see where the original track was edited so as to remove the portions that mentioned Meadows. The 1991 version, on which Zappa restored the censored portions, is missing only a brief passage. The Läther version is also not censored, but matches the original release in editing out other portions of the December 29th performance.

from Information Is Not Knowledge

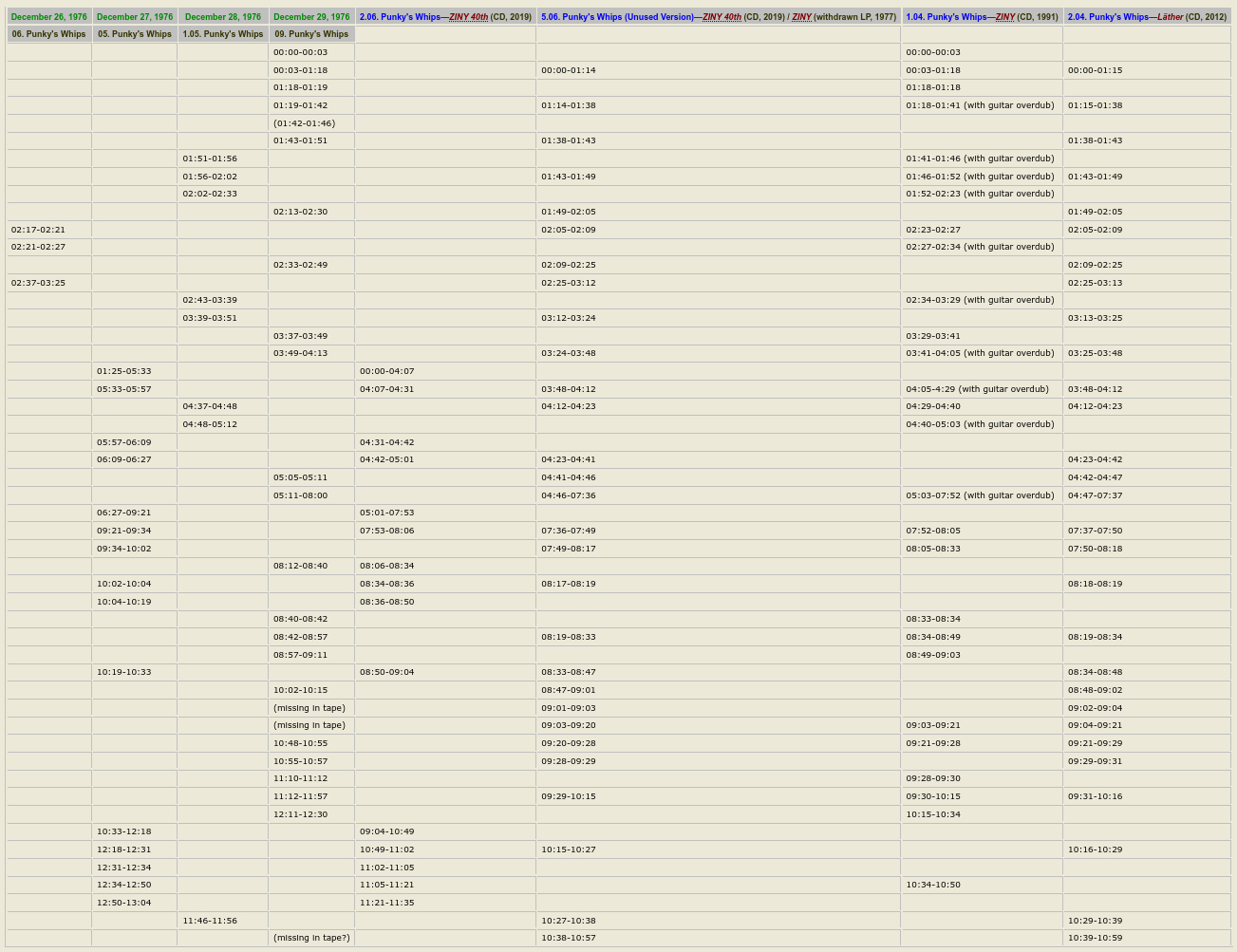

We can also see from the Information Is Not Knowledge tables how four versions of ‘Punky's Whips’ (the 1991 C. D., the Läther, and a new edit on the disc 2 of the box set, plus the original removed from the 1978 album) were all made out of portions of the song's performance on each of the four nights. Such was Zappa's obsessive editing. The original, now called ‘Punky's Whips (Unused Version)’, actually corresponds to the Läther edition, so its release in the box set is not noteworthy (except that it is mastered differently); the original also almost corresponds to the 1991 version, but the latter had overdubs (Zappa made such additions to several tracks after the concerts). Even the alternate on disc 2 overlaps considerably with the other versions, though it does include significantly more material from the December 27th concert.

from Information Is Not Knowledge

Having unedited and additional performances of these censored songs would have been enough to make a reissue of Zappa in New York noteworthy. As we start to look at the bonus material, we see that the decision to release a full box set, while undoubtedly leaving most listeners with more than they ever wanted, nonetheless was a wise move. As explained in the liner notes, a box set similar to the The Roxy Performances was not an option, as the cutting and pasting of the tapes for the original double L. P. had not left complete documentation intact. But, I say, we have enough. The conspicuous example of this comes with the version of ‘Black Napkins’ on the set's fourth disc. Having just been released on Zoot Allures, this new instrumental piece, a showcase for Zappa and other soloists, appropriately takes a prominent place during the New York shows. Few could have expected, though, the performance enacted at the December 29th concert, more than 28 minutes in length. Besides solos from the two Brecker brothers, Zappa and Jobson take star turns (Jobson on violin), both using electronic effects to brilliant effect. While other Zappa pieces at times stretched out to the 20-minute mark, for example ‘Dupree's Paradise’, only performances of longer narrative works like ‘Billy the Mountain’ and ‘The Adventures of Gregory Peccary’ tend to pass the 30-minute mark.

The remainder of the bonus material on the second-fifth discs of the box is not as revelatory but overall forms an extraordinary contribution to Zappa's oeuvre. As with the ‘Napkins’, some of the performances are of songs not heard on the original New York double album, such as ‘Peaches en Regalia’, ‘The Torture Never Stops’, ‘Penis Dimension’, ‘Montana’, ‘America Drinks’, ‘I'm the Slime’, ‘Pound for a Brown’, ‘Dinah-Moe Humm’, and ‘Find Her Finer’. Others are alternate performances. For example, we get ‘The Black Page Drum Solo/Black Page #1’ from December 29th, whereas the album version was from December 28th. The ‘Big Leg Emma’ on the album comes from December 28th; disc 3 has the December 29th rendition. ‘Black Page #2’ on the album is from December 28th, disc 2 has a version mostly recorded on December 29th but with a conclusion from the 27th. The album version of ‘The Legend of the Illinois Enema Bandit’ comes from December 29th, while disc 2 has the complete December 28th performance plus an introduction from December 27th.

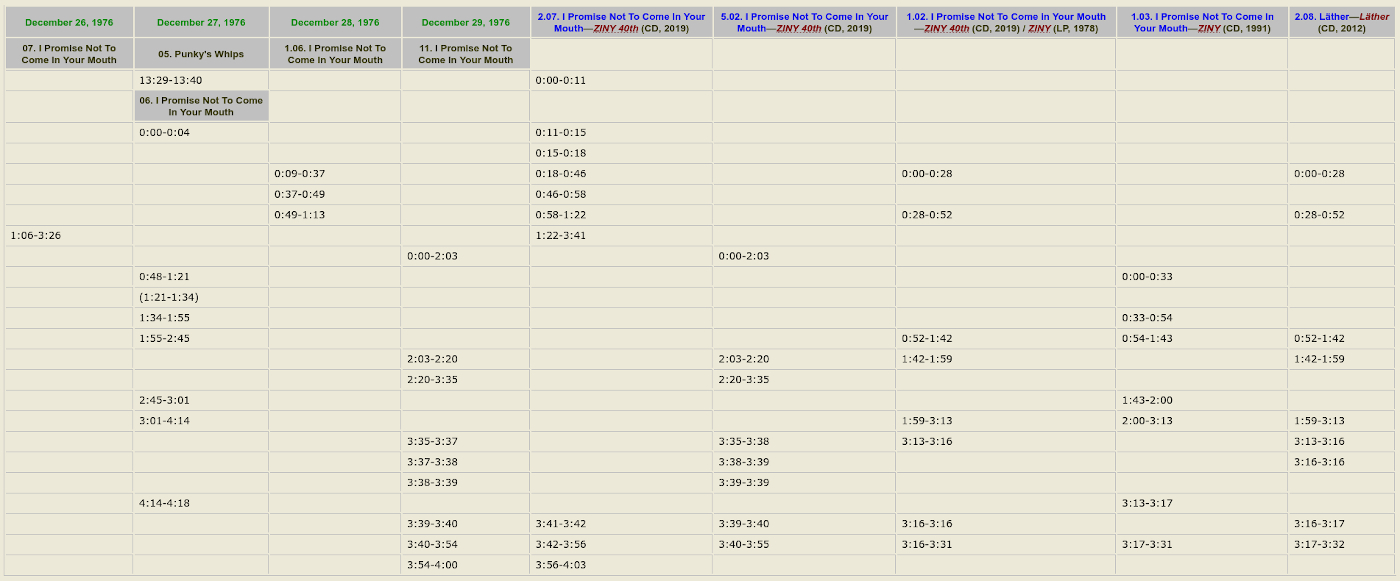

from Information Is Not Knowledge

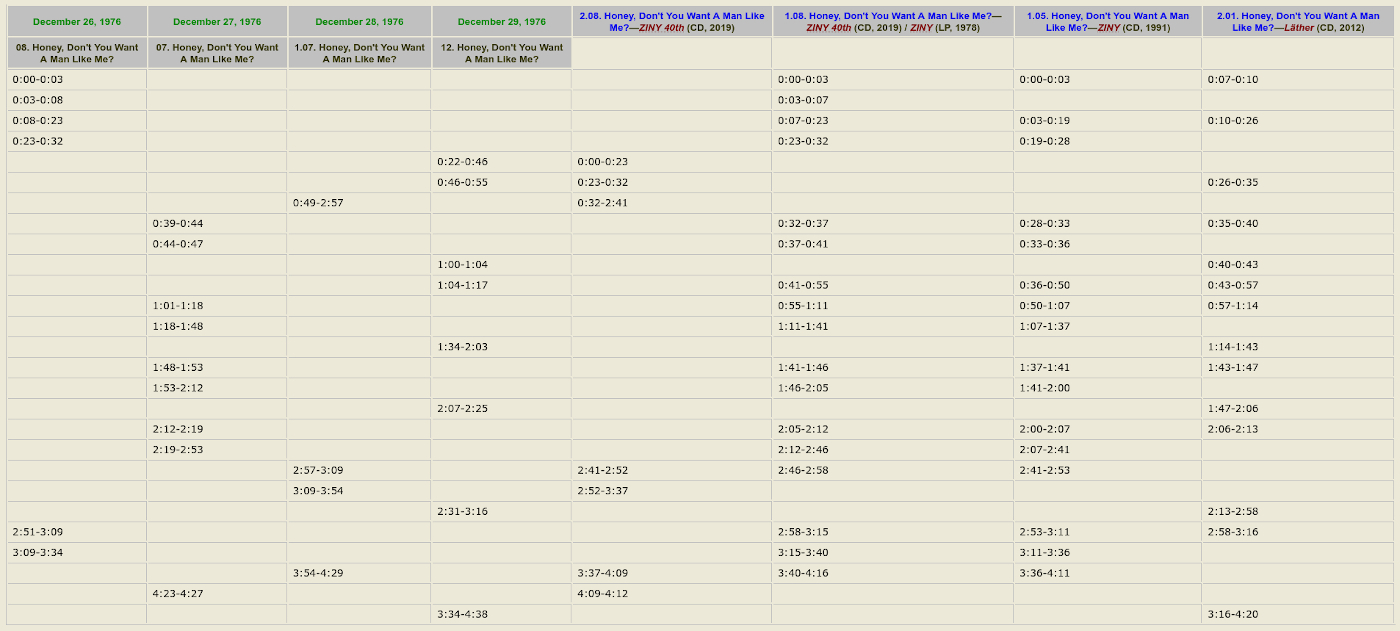

Others still are alternate edits, or complete performances out of which excerpts were taken to form the album versions. Confusing? Yes. An example: on ‘I Promise Not to Come in Your Mouth’, as seen above, in the versions heard on the original New York, the 1991 C. D. version of the album, and Läther (all different edits, however slightly), one hears portions of the performances on the 27th, 28th, and 29th. As if that was not enough, we have an additional edit on discs 2 and the complete performance from the 29th on disc 5. Similarly, disc 2 has a different edit of ‘Honey, Don't You Want a Man Like Me?’, consisting of material from the 28th, whereas the original New York and Läther edits were derived from all four concerts (but only a brief portion of the 28th, thus the decision to make the disc-2 alternate being virtually a straight documentation of that performance; again, consult the table, shown below). While the long performance of ‘The Purple Lagoon’ found on the original album contains portions from the 27th, 28th, and 29th, on disc 4 we have ‘The Purple Lagoon/Any Kind of Pain’ from the December 26th concert, while the complete December 29th performance is on disc 3, as seen in the table below. The version of ‘Cruisin' for Burgers’ heard on the 1991 C. D. New York is heard on disc 5 without overdubs. And an edit of a shorter performance of ‘Black Napkins’ previously released, in part, on You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore Vol. 6 (where it was collaged together with a 1984 performance!) is found on disc 5.

from Information Is Not Knowledge

from Information Is Not Knowledge

Surely, from all this extra material, an alternate version of Zappa in New York could be put together—right? Maybe. Of course the inclusion of ‘Punky's Whips’ and the uncensored ‘Titties & Beer’ would restore the original album to its proper double-album length (instead of the one hour that it was cruelly demoted to). Other reconceptualizations of this album, however, should only proceed after we consider Läther, the alternate home of much of the New York material.

--

The "great lost Zappa album," as stated on the sleeve of the 1996 Rykodisc triple C. D. that served as its belated official release, is of course Läther, originally sequenced by Zappa as a quadruple album in 1977. As the legend goes, Warner would not release the material in such a gargantuan form, and so Zappa in New York and three other albums, Sleep Dirt, Studio Tan, and Orchestral Favorites, all constructed from the same material, came out instead. The reality is messy, especially the chronology. Zappa apparently provided the four separate albums to Warner, but knew that, due to the growing tensions noted above, the label were not likely to release them. If they did so, Zappa, who owed them four albums, would be free from his contract with them. Zappa alternately sequenced material from those four albums as Läther, having played it on the air, encouraging listeners to dub copies, tried to convince several record labels to put it out. A release appeared imminent in late '77 until Warner interfered, deciding finally to release the four separate titles. In other words, while they had assumed Zappa did not actualy want the release all the material at once, Zappa called their bluff and not only was willing to release it, but to do so in a different sequence, four L. P.s created to be a singular listening experience. Zappa in New York, the first of the four albums that Warner now wanted to release, was going to come out in '77 until the label's censoring of the Punky Meadows-themed portions caused a delay until early '78.

Since we are in Zappa world here, where nothing is simple, the four separate albums do not offer exactly the same music as Läther. There are songs on the latter not found on any of the four, and three of the four albums (excluding Studio Tan) have songs not found on Läther. And at times the songs that are shared between the two sets of recordings are edited differently, or are different recordings entirely; and on top of that, Zappa made changes when he released C. D. versions of the four separate albums—and there were a few bonus tracks on the '96 Läther release (inconveniently removed on the 2012 reissue). And, yes, there is even more: a few Läther tracks ended up on Sheik Yerbouti [1979], Joe's Garage [1979], and Tinsel Town Rebellion [1980], a scattering of material similar to what happened to Chrome Dreams and Captain Beefheart's Bat Chain Puller.

While there has been hoopla about, even a bit of mythologizing about, Läther, especially with the publicity surrounding its official release in '96, the four separate albums (which—again, as far as we know—should have come out first, all released in '77 or at least beginning to come out then) overall make for a better way of experiencing the music involved. Always the master studio editor, Zappa certainly pulled off quite the feat in concocting a quadruple album consisting of both studio and concert material. But too often the contrast between the serious material and the humorous songs is tiring. Of the six tracks found on Läther not on any of the four albums, four fit into the category of Zappa's silly, satirical songs (‘Tryin' to Grow a Chin’ and ‘Broken Hearts Are for Assholes’ are the songs that found a home on Sheik Yerbouti, and a different version of ‘A Little Green Rosetta’ is on Joe's Garage Acts II & III and a different version of ‘For the Young Sophisticate’ is on Tinsel Town Rebellion). The other two, ‘Duck Duck Goose’ and ‘Down in de Dew’, are more experimental, and would have fit in on either Studio Tan or Sleep Dirt. Furthermore, the way in which the smuttier Zappa in New York material is sequenced throughout Läther makes the quadruple L. P. too focused on the Zappa narrator's wry, cynical takes on contemporary sociopathic youths and their crude attempts at courtship and romance. Indeed, as a composer eager to get his longer, non-Rock works performed and heard, Zappa inexplicably gives the Orchestral Favorites material an inferior position, with the two tracks that would comprise that album's second side, ‘Duke of Prunes’ and ‘Bogus Pomp’, excluded from Läther.

My preference for the four distinct albums, instead of Läther, takes me back to possible expanded versions of Zappa in New York promised above (keep in mind too, as noted above, that an excellent expanded version of Orchestral Favorites was released in 2019, with the album's original stereo mix restored and two C. D.s of bonus material from the September 1975 concerts from which that album was made). Indeed, perhaps Zappa in New York is the one that should have been the quadruple album. First, we must remember that the 1991 C. D. version not only included ‘Punky's Whips’, but also versions of ‘Cruisin' for Burgers’, ‘I'm the Slime’, ‘Pound for a Brown’, and ‘The Torture Never Stops’. The versions of three of these four tracks, though, do not derive from the particular performances heard in the box set. As noted above, the December 29th ‘Cruisin for Burger’ used for the '91 album is thankfully presented on the fifth disc as the "1977 Mix," without Zappa's overdubs. (Disc 3, meanwhile, includes a version of the song with portions from both the December 26th and 27th concerts.) The other three tracks, unfortunately, are not found in the box set; that is, we cannot hear them in vintage mixes. The ‘I'm the Slime’ in the '91 release is from December 26th and 27th, whereas the version on disc 3 of the box is from December 29th. Regardless of overdubs, neither are worthy of much attention; Don Pardo's guest performance, unlike those on ‘Punky's Whips’ and ‘The Illinois Enema Bandit’, is sloppy, likely poorly-planned. The ‘Pound for a Brown’ heard on the '91 double C. D. comes almost entirely from the December 26th concert, while the performance on the third disc of the box set derives from the December 27th, with an introductory portion from the 29th; the box-set version is better—and, besides, the overdubs do not help. ‘The Torture Never Stops’ on the '91 set comes from the December 29th show, while the second disc of the box set features the December 27th performance; the latter is, in my opinion, considerably better. While, above, I mentioned that I would always prefer a vintage Zappa edit, given the post-concert overdubs and the remix unique to the '91 release, these edits are not as vintage as we would like; the '91 album for me remains on its own as the most-alternate of several alternates.

So what is included in my imagined quadruple-L. P. version of Zappa in New York? The 28-minute ‘Black Napkins’ already needs one L. P. to its itself. ‘Pound for a Brown’ (disc 3, track 6), ‘America Drinks’ (3-1), and ‘Peaches en Regalia’ (2-2) should definitely get included as fine examples of earlier Zappa tunes adapted to a different setting. ‘Cruisin' for Burgers’ (5-4) is another earlier tune significantly expanded for these concerts, and without the overdubs is excellent, as is the version of ‘Purple Lagoon’ matched with ‘Any Kind of Pain’, a tune otherwise only heard on the Eighties concert album Broadway the Hard Way. Another rare composition, ‘Penis Dimension’ (2-11), is a highlight and leads straight into a performance of ‘Montana’, which of all recent album tracks heard in this set ranks the highest; the rendition of ‘Find Her Finer’ (3-12) is great too, but sort of breaks down toward the end due to some audience interaction—that is, something that would work well on film. Perhaps many would want to include the aforementioned December 27th ‘Torture Never Stops’, but it would make for one album longer than the other three, its Zappa solo is hardly noteworthy, and backing tapes from the recording are poorly incorporated into the live mix. Finally, ‘Terry's Solo’ (3-7) flows right out of ‘Pound for a Brown’ in the original performance; its inclusion adds some sonic variety and further emphasizes Bozio's starring role.

The track listing for this quadruple album that combines (nearly all of) the uncensored 1977 double L. P. with these box-set highlights could run as follows. I prefer the censored ‘Titties & Beer’ because, a reference to the third track, ‘Punky's Whip’, on the first track of the album does not quite work. But if you prefer the extra 20 seconds being there, you can use the Läther version, which, though mastered differently, matches the 1977 edit.

A:

‘Titties & Beer’ [1978 version; disc 1, track 1 in the box set]

‘I Promise Not to Come in Your Mouth’ [1-2]

‘Punky's Whips’ [5-6]

B:

‘Sofa’ [1-4]

‘Manx Needs Woman’ [1-5]

‘The Black Page Drum Solo/Black Page #1‘ [1-6]

‘Big Leg Emma’ [1-3]

‘Black Page #2’ [1-7]

C:

‘Honey, Don't You Want a Man Like Me?’ [1-8]

‘The Illinois Enema Bandit’ [1-9]

D:

‘The Purple Lagoon’ [1-10]

E:

‘Black Napkins’ [4-3]

F:

‘Black Napkins’

G:

‘America Drinks’ [3-1]

‘Peaches en Regalia’ [2-2]

‘Pound for a Brown’ [3-6]

‘Terry's Solo [3-7]

‘Cruisin' for Burgers’ [5-4]

H:

‘The Purple Lagoon/Any Kind of Pain’ [4-1]

‘Penis Dimension’ [2-11]

‘Montana’ [2-12]

In the end, as much as we can wish that Zappa never faced obstacles to releasing his music in this crucial period, 1976-1979, these challenges arguably being impossible for him to transcend, we are left with multiple versions of several important Zappa compositions, none of which can be claimed to be the primary, or official version. What if Zappa had wanted to release both Läther and the four separate albums? As if to say, take your pick—but be sure to pick of all of them. Indeed, what if another artist, lost in his own archives, did precisely that? Different versions of songs, or in some cases the same version of a song, released on multiple albums? Thusly we arrive at Neil Young, especially his "lost album" Chrome Dreams.

–Justin J. Kaw, December 2024